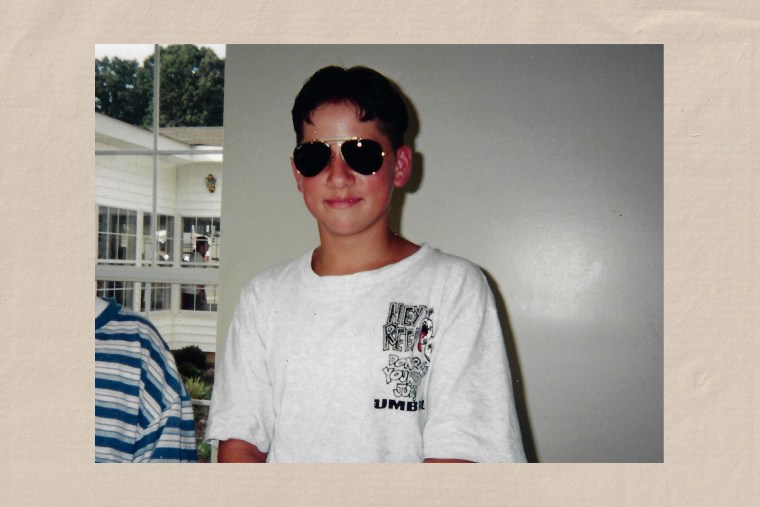

Chris Woods Sr. says church leaders in Florida dismissed his plea for help when he reported being sexually abused by his Royal Rangers commander in the mid-1980s. Around 7 at the time, Woods said he felt powerless and alone.

“The first word that comes to mind is shame,” he said. “That kind of becomes your core belief of who you are.”

Scouting America, a much larger organization formerly known as the Boy Scouts, faced similar horrors. In response, the group overhauled its youth protection system over the past four decades: barring adults from being alone with children, mandating background checks and abuse-prevention training, and requiring any suspected abuse be reported to authorities. While it’s not a fail-safe system, attorneys who represent sex abuse survivors say the measures have helped protect children.

Assemblies of God leaders have for decades urged local churches to adopt comparable safeguards for Royal Rangers troops, which are run by individual congregations both within and outside the denomination. But unlike Scouting America, the Assemblies of God leaves the protections optional.

Gilion Dumas, an Oregon attorney who has represented survivors of abuse in both scouting programs, said the Christian tenets guiding the Royal Rangers — which emphasize grace and second chances — can allow perpetrators to go unchecked.

“Forgiveness and redemption are good qualities,” she said. “But you can’t gamble with the safety of children.”

‘Pastors and Prey’: NBC News investigates sex abuse in Assemblies of God churches

The General Council of the Assemblies of God, the denomination’s U.S. governing body, declined interview requests. In statements, it said it “condemns child abuse in all forms” and grieves for victims.

The General Council said churches participating in the Royal Rangers may voluntarily charter their outposts with the denomination’s national office — a step that gives them discounts on materials and inclusion on an online map, which lists about 400 troops. To become chartered, the General Council said, local chapters “must affirm they have adopted a process for screening and supervision” of leaders, including criminal background checks.

When pressed, denomination officials acknowledged that “the overwhelming majority of churches using Royal Rangers curriculum choose not to charter,” which means most troops aren’t required to affirm that they have adopted safety measures. The Assemblies of God has no official count of unchartered troops.

The denomination’s approach to child safety is rooted in part in the belief that local churches should be free to govern themselves. It has also served as a legal defense, with the General Council repeatedly arguing in court that it can’t be held liable for abuse because it doesn’t control individual troops.

Victor Vieth, a former child abuse prosecutor who works for the nonprofit Zero Abuse Project, said scouting programs are inherently high-risk because they attract perpetrators seeking access to children, and boys are less likely to disclose abuse. The Royal Rangers’ structure, he said, is especially dangerous because offenders need only to deceive a local church, rather than a national organization.

By failing to enforce stringent policies, Vieth said, the Assemblies of God has “lit a fuse.”

“And on the other end of that fuse,” he said, “will be the sexual abuse of children.”

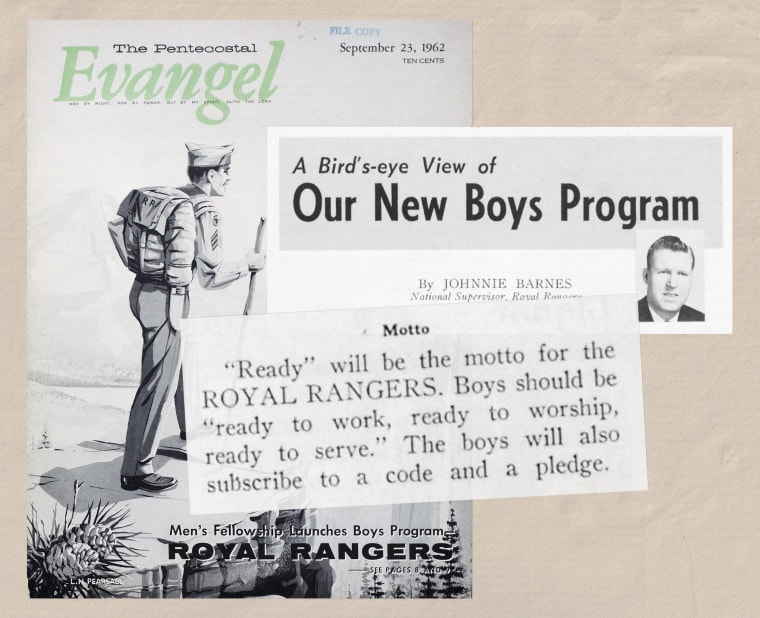

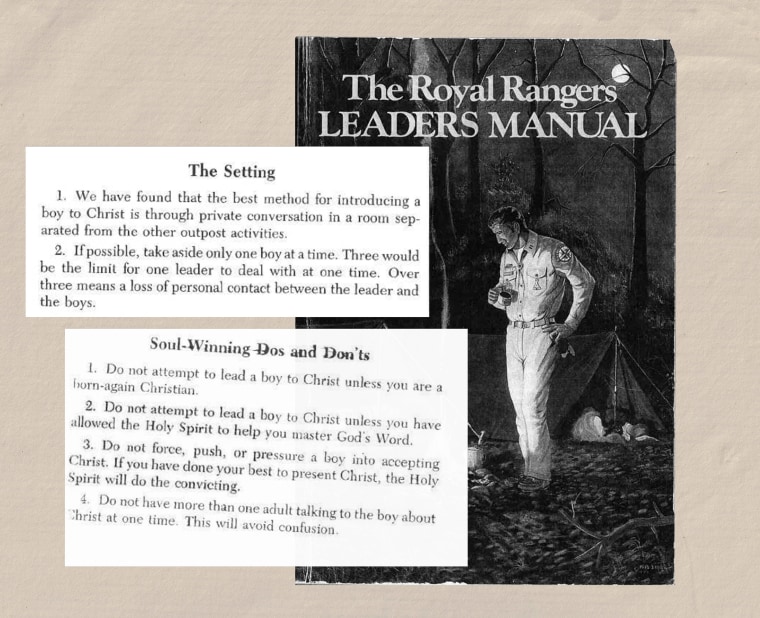

The Royal Rangers launched in 1962 as a church-run alternative to the Boy Scouts — promising the same campfires and camaraderie, but with an evangelical mission. It wasn’t just about pitching tents or using a compass. It was about raising soldiers for Christ.

To many Pentecostals, the stakes couldn’t have been higher. The sexual revolution and shifting family values stoked fears that society was sliding into darkness. Royal Rangers founder Johnnie Barnes warned in the Assemblies of God’s Pentecostal Evangel magazine that “a new age is upon us,” one marked by “pleasure madness” and “moral indifference.” Unless godly men intervened, he wrote, boys “will be the victims of it.” His program promised to save them through discipline and Scripture.

For decades, that vision defined boyhood in Assemblies of God churches — weekend treks with trusted male leaders, campfires glowing against the night. But the very spaces created to protect boys from a sinful world sometimes became places where evil found them: a camping trip in Oklahoma. A tent in Illinois. A church basement in New York.

In some instances, Christian teachings meant to set the Royal Rangers apart from other scouting programs were twisted to justify abuse, according to lawsuits. One leader allegedly told boys that masturbating each other was what Jesus’ disciples did. Another knelt down in prayer, telling a boy he was asking God for forgiveness for what he was about to do to him.

Ralph Wade Gantt and Todd Scott Clark were in their 20s when they led the Royal Rangers troop that Travis Reger attended at Albany First Assembly of God in Oregon. They held Bible studies and taught the boys how to tie camping knots. Both men often hosted sleepovers — gatherings that became central to one of the Royal Rangers’ most disturbing abuse cases.

For Reger, the first time was so subtle that years passed before he understood it was abuse. Around 1984, he and other boys were sprawled on Gantt’s living room floor watching a movie when Gantt began rubbing his back. Reger says Gantt then slid his hands up his legs, hooking his fingers beneath Reger’s underwear.

The next violation, later in 1984, was unmistakable: Reger says Clark masturbated him and another boy in his bed after an evening of play-sword fighting and watching TV. For many years afterward, Reger blocked out the panic he felt as he rolled onto his stomach to stop the assault — and the guilt of hearing Clark turn to the other boy instead.

Back home, Reger confided in his father. Indignant, Tom Reger confronted a pastor at the church, Stan Baker, at that week’s Royal Rangers meeting. Baker, Tom Reger later said in a deposition, simply told him “they were aware of the situation” and that Clark was in counseling.

“He knew all of it,” Tom Reger told NBC News. “I’m not going to say he encouraged it, but he was involved in trying to keep it quiet so that the great Assembly of God church’s reputation wouldn’t be sullied.”

Again and again in the years that followed, the Albany church received complaints about Clark and Gantt — and again and again, Baker and other leaders kept letting the pair take boys on campouts and into their homes, according to lawsuits and interviews. In legal filings, the church asserted that it received no abuse reports before 1986. At that point, church leaders suspended the men and sent them to counseling rather than alert police, court records show.

The police didn’t get involved until 1987, when a 12-year-old told authorities he had been molested. Gantt was convicted of sexually abusing and sodomizing the boy and a pair of brothers. Clark was also convicted of abusing the brothers. Gantt was sentenced to 10 years in prison, while Clark was sentenced to 15, court records show.

At least 15 other boys also described being abused by the pair, ranging from being watched in the shower to being raped, according to an NBC News review of police records and lawsuits. Clark declined to comment; Gantt could not be reached.

Baker, still a pastor at the church, declined to be interviewed, saying in a text message that “the safety of the children involved in our programs is our top priority.”

Shortly after Gantt and Clark were convicted in 1988 of abusing her two sons, Debra Dodson, a single mother, sued both men, the church and the national Assemblies of God organization, seeking $9 million in damages.

Dodson told NBC News she had no idea that in between boxcar races and Bible lessons, the men were abusing her sons, who were about 10 and 12 at the time.

“I didn’t really have a male influence in their lives,” she said. “I leaned on them heavily.”

She only learned what had happened when an investigator came to her home to interview her boys around 1987.

Dodson carried guilt, but she also blamed the Royal Rangers. “There were no safety guidelines,” she said. “None.”

By filing one of the first Royal Rangers lawsuits to name the Assemblies of God’s national office as a defendant, Dodson had put the denomination on notice of dangers in its scouting program. Other national youth organizations were facing similar allegations and began adopting safety rules — screening volunteers, requiring two adults present at all times and promptly reporting suspected abuse to authorities.

But unlike those organizations, which responded with mandatory safeguards, the Assemblies of God merely urged local congregations to adopt such measures. At the same time, the denomination was distancing itself from legal responsibility.

Dodson eventually settled her lawsuit with the church, but only after following her lawyers’ advice to drop the national church organization as a defendant, a decision she now regrets.

Afterward, the denomination’s longtime chief legal counsel, Richard Hammar, declared victory.

The plaintiff, Hammar told a newspaper reporter, had conceded that the Assemblies of God “did not exercise supervision or control” over local Royal Rangers groups — a separation the church has fought to preserve ever since.

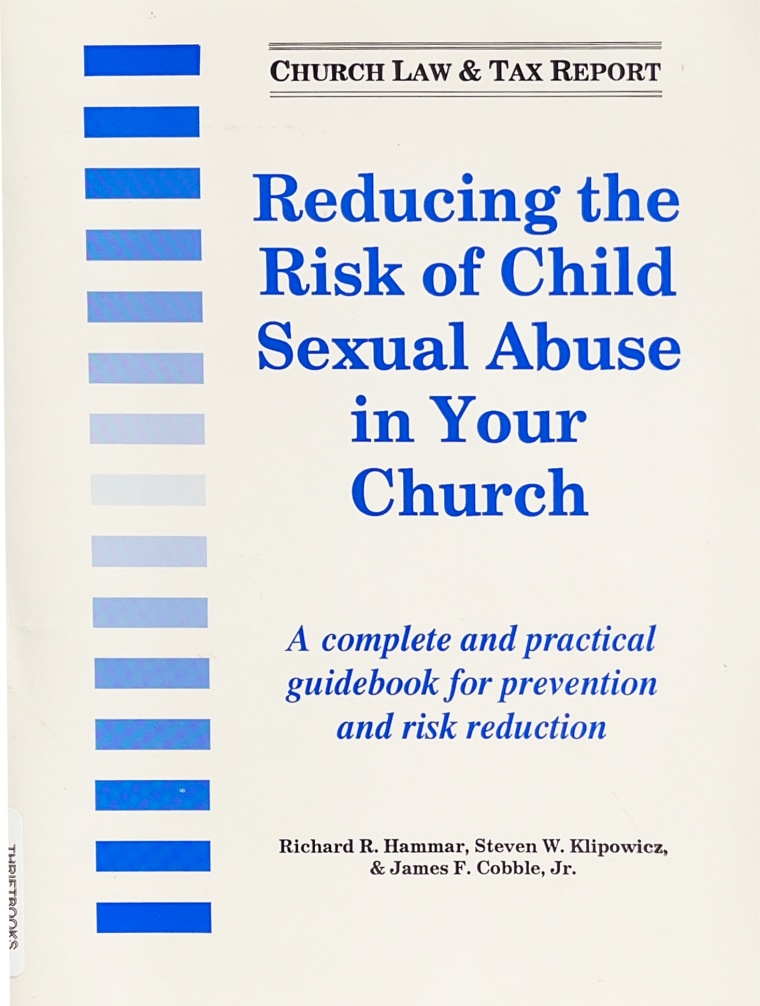

As reports of sexual abuse mounted across its congregations, the Assemblies of God unveiled a solution in 1993: an educational program developed by Hammar called “Reducing the Risk.” Packaged in books, cassettes and VHS tapes, the initiative promised to teach churches how to prevent abuse while protecting themselves from liability.

One video from the series delivered a blunt warning: “Other charities, such as the Boy Scouts and Big Brothers, have instituted very effective screening procedures. As a result, the pedophile or the child molester is migrating to the last institution where he can be placed in immediate contact with potential victims in an atmosphere of blind trust, and that’s the church.”

But with no requirement, some Assemblies of God churches didn’t adopt the safety measures. At Saraland First Assembly of God in Alabama, Brandon Champion said he bore the cost.

He was about 13 when his Royal Rangers leader, Samuel Arthur Thompson, took an interest in him in the mid-1990s. Thompson built remote control helicopters and invited Champion to stay the night, promising to teach him to fly them.

The attention turned predatory. Champion recalled waking to find Thompson’s hands inside his pants. Other times, he said, Thompson groped him while camping.

The grooming and abuse continued for two years before Champion typed a letter to his pastor, Ken Draughon: “I do not know if I am the first person whom he has treated, or rather mistreated in this manner,” Champion wrote. “However, I would prefer to be the last.”

Champion’s mother, Maggie, hand-delivered the note to Draughon, who told her he would “take care of this,” she later testified. But Draughon didn’t call the police, according to depositions and trial testimony. Weeks later, Maggie Champion went to authorities. Thompson was convicted of sexual abuse and sodomy and sentenced to three years in prison.

Draughon, now superintendent of the district council that oversees Assemblies of God churches across Alabama, didn’t respond to messages. Neither did Saraland First Assembly. Champion and his mother won a civil judgment against Thompson in 2006 but never received any money. Last year, Thompson was labeled a “prolific child molester” by federal officials and sentenced to 220 years in prison on new abuse charges.

Champion remains angry at the denomination, comparing its leaders to the religious authorities Jesus rebuked in the New Testament for putting power and pride above justice and compassion.

“If you’ve actually read the Bible and you believe the things in there, I don’t know how you could let so many children and innocents come to victimization,” he said, “without taking some sort of affirmative action.”

Tasked with preaching the word of God, Royal Rangers leaders sometimes conveyed far more nefarious messages. Around 2013, an Olney, Texas, troop commander warned a 6-year-old boy he’d been abusing that if he told anyone, he would kill the child’s family, according to the boy’s mother.

The boy stayed silent, and for about two years, Royal Rangers leader Ryan Anthony Winner not only sexually assaulted the child but also recorded nude photos and videos of him, court records show.

He was caught when an Australian undercover officer thousands of miles away from First Assembly of God in Olney discovered graphic photos of the boy in online albums Winner had labeled “My Son,” the records show.

Winner was arrested in 2015 and was sentenced to 60 years in federal prison after pleading guilty to producing child sexual abuse material. He explained his perverse code of honor to authorities, according to a criminal court filing: He never abused the boy during Sunday services because he didn’t want to taint the child’s relationship with God.

The boy’s mother, whom NBC News is not naming to protect her son’s identity, filed a lawsuit alleging that Winner had a “propensity” for sexually abusing children, yet the Olney church placed him in a leadership position anyway. She settled with the church and the Assemblies of God’s North Texas district council, but she told NBC News she’s furious at the denomination for allowing decades of abuse without meaningful reform.

“Why would you not protect the next generation from predators?” she said.

For decades, many who say they suffered in the Royal Rangers kept their pain buried. Now, scores of them are speaking out.

In the last four years alone, former Royal Rangers participants have filed at least 17 lawsuits alleging sexual abuse, court records show. They accuse Assemblies of God churches of shielding predators and ignoring warnings.

Many say their abuse shaped everything that followed: years of addiction, struggles with self-harm, a lasting loss of trust in religion. The Assemblies of God’s national office has sought to be dismissed from recent lawsuits, arguing just as it had decades earlier that it holds no authority over Royal Rangers outposts — and therefore bears no responsibility for lives crushed by them.

In a podcast interview last year, the Assemblies of God’s national leader described an influx of sex abuse litigation, including the Royal Rangers lawsuits, as a top challenge facing the denomination.

“That’s becoming an ever-increasing burden that I would appreciate the prayer of our fellowship on as we navigate through these times,” general superintendent Doug Clay said.

For survivors like J.M.R. of Oregon, the denomination’s response is unacceptable. He says that after his Royal Rangers commander molested him and other boys starting in the late 1970s, his pastor urged families to forgive the man.

Last year, J.M.R. sued the Assemblies of God’s district office in Oregon and its national headquarters; the case is ongoing.

“It’s a child molester’s perfect situation,” J.M.R. said. “No process. No protocols.”

The Royal Rangers code urges boys to live by truth and bravery. In coming forward, some say they’re doing exactly that — and calling on the Assemblies of God to do the same.