Leah Boustan and William Collins in NBER Reporter summarise recent research on Development of American economy:

The Development of the American Economy (DAE) program was one of the first research programs launched by Martin Feldstein in 1978 when he formalized the modern structure of the NBER.

The mission of the program is to research historical aspects of the American economy. Its members are economic historians whose specific interests span many subfields within economics, including macroeconomics, labor economics, finance, political economy, trade, and industrial organization. Broadly, economic history research comes in two flavors. First, economic historians study the evolution of economic trends that illuminate issues relevant to the modern economy, such as the entry of women in the labor force and the moderation of economic crises over time. Second, economic historians use the natural experiments offered by history to test economic theory and identify causal channels that may drive important economic change.

Recent work by Robert Margo demonstrates the continued integration of economic historians into mainstream economics.1 Of articles published in the field’s flagship journals such as The Journal of Economic History and Explorations in Economic History, 20 percent contained econometric language in 1970—words like “regression”—and now 70 percent do. Earlier cohorts of economic historians published 36 percent of their articles in economics journals (outside of economic history journals), whereas more recent cohorts publish 75 percent of their articles in these venues.

Given the wide span of interests and expertise of DAE program affiliates, research topics cover many areas, including health, the environment, banks, financial crises, corporate governance, education, migration and immigration, and intergenerational mobility. In recent years, affiliates have responded to global events by increasing their focus on historical pandemics, industrial policy, and trade. Text analysis, the use of large language models, and machine learning are among the new methodological areas of interest used in the group.

This report highlights research in four areas: innovation and manufacturing, economic mobility, banking and finance, and women in the economy.

On Banking and Finance:

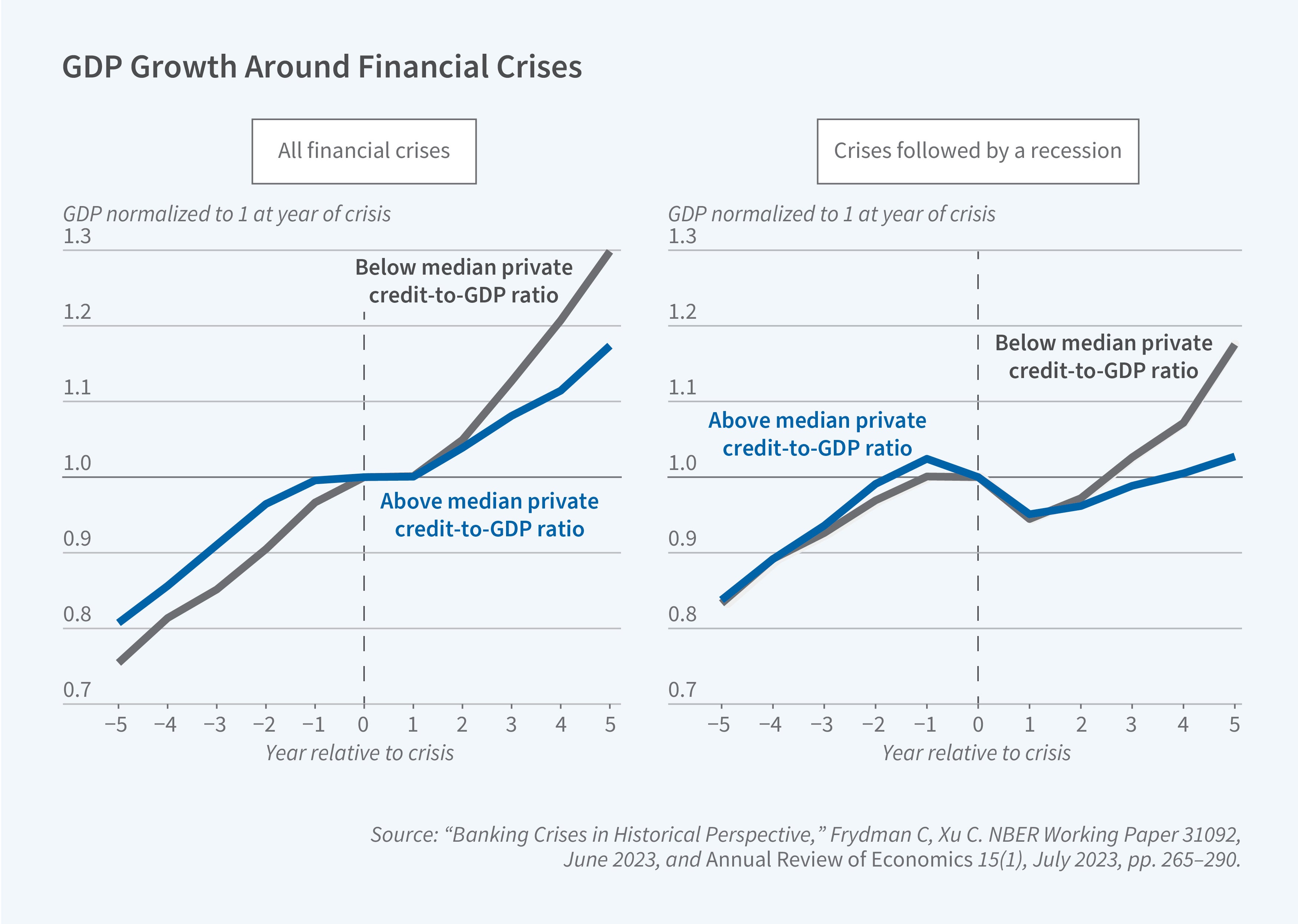

Recent research has continued to advance our understanding of bank failures and financial crises. Frydman and Xu review the last 20 years of research on banking crises, highlighting the value of long-term perspective, the importance of leverage in the financial system as a precursor to crises, the negative and often long-lasting impacts on the broader economy, and the important role that timely government responses can play in offsetting panics.28

A substantial body of research examines banking during the Great Depression, when waves of bank failures fueled the economy’s downward spiral. Most places in the US lacked branch banking in the early twentieth century, a feature of the American economy that may have left it especially vulnerable to financial crises. Quincy shows that Bank of America’s branching system in California, the largest in the country, improved local credit and economic outcomes during the Depression and beyond. Bank of America’s geographic diversification and internal movement of capital insulated its branches from local shocks, in contrast to local unit banks and small branch networks.29 Mitchener and Richardson assemble new datasets from bank balance sheets and show that banks that survived the early 1930s significantly contracted their lending, accounting for a large fraction of the total decline in bank lending.30 Mitchener and Vossmeyer find that the closure of thousands of banks during the Depression did little to reduce risk in the financial system; that is, there was no “cleansing effect” from the closures.31 Instead, acquisitions merely redistributed the risk to healthier banks.

In the absence of deposit insurance, banking panics in the early years of the Great Depression were common. President Roosevelt declared a “bank holiday” in March 1933 to assess banks’ health and then allowed individual banks to re-open over time. Jaremski, Richardson, and Vossmeyer show that this sequential re-opening conveyed noisy information about banks’ health and resulted in financial resources shifting across banks and communities.32 The stigma of banks re-opening late lasted for a decade, but this was not detrimental to local commercial or industrial activity. The US Postal Savings System did insure deposits. This was a haven for depositors, but it may have exacerbated liquidity risk for local banks. Jaremski and Schuster show that banks operating near post offices that accepted deposits were more likely to close in the early years of the Depression, a reflection of depositor withdrawals.33

Recent research has also drawn on historical experience to better understand financial markets. For instance, Bernstein, Frydman, and Hilt study the introduction of Moody’s ratings for corporate securities in 1909.34 Even though the ratings had no regulatory implications, lower-than-expected ratings caused a rise in market bond yields and bonds that were rated by Moody had reduced bid-ask spreads, consistent with improved liquidity and information transmission. Cortes, Vossmeyer, and Weidenmier investigate the “war volatility puzzle” (i.e., the relatively low level of US stock volatility during wartime, even during World War II).35 They hypothesize that government-guaranteed contracts reduce the uncertainty of firms’ earnings, which is consistent with new, hand-collected military spending data spanning more than 100 years, as well as with micro-level analyses. In another paper connected to the economic ramifications of war, Brunet, Hilt, and Jaremski find that Liberty Bond drives during World War I had lasting effects on households’ financial behavior, as evidenced in mid-twentieth-century data on stock and bond ownershi