In my commissioned research activities, which are separate from the basic academic research that occupies most of my time, I come across interesting situations which bear on the way monetary systems operate and the type of constraints faced by different levels of government. In Australia, we have three levels of government: Federal (currency issuer), State and Territories (currency users), and Local government (currency users). Our constitution also confers the major spending responsibilities – education, health, transport, etc on the states and territories despite them having few legal means to raise revenue, which has been a major problem since Federation. If one then embeds that constitutional fact into the fictional mainstream economics narrative that says the currency-issuing federal government is like a household – that is, is financially constrained in its spending. So public debt becomes a media issue. After the pandemic, the federal and state governments were left with significant increases in debt liabilities that has led the state governments to impose austerity cuts and hike taxes. The Victorian state government has recently hiked a levy on land ostensibly to provide extra funding for emergency services. The problem is that the campaign against this tax hike is bringing together an array of anti-progressive elements who just want a change of government. Their campaign, which is roping in progressives who don’t seem to understand the issues, cannot answer how the fire services, which have been underfunded for years as a result of an austerity mindset and facing major equipment deficits and wage demands, will be able to provide adequate services with such a tax hike. The land tax is a progressive tax and the best source of revenue to improve the fire services which are essential to the community. Once again the buy-in to the anti-tax campaign is a case of progressives shooting themselves in the foot.

Background

When the Pandemic hit Australia in March 2020, the the Federal and State (I will just use State for State and Territories) governments introduced rather wide-ranging restrictions of activity and movement while health authorities worked out what was going on and while they waited for a viable vaccine to be made available.

Accompanying those restrictions, were significant fiscal interventions – income support and other measures – which saw the fiscal balances of the various levels of government move into larger deficits.

Between 2018-19 and 2020-21, the federal fiscal balance went from zero as a per cent of GDP to 4.3 per cent in 2019-20, then 6.4 per cent in 2020-21.

Between 2018-19 and 2019-20, the total All states operating balance went from a surplus of $A5,219 million to deficit of $A26,337 million.

These were quite stunning fiscal shifts at both federal and state levels of government.

The federal government and the governments of the three largest states recorded the following fiscal balance shifts between 2018-19 and 2019-20:

| Government | 2018-19 $m |

2019-20 $m |

| Australia | +4,252 | -89,116 |

| NSW | +1,459 | -8,111 |

| Victoria | 1,488 | 8,701 |

| Queensland | 734 | 6,235 |

Again, I emphasise the enormous scale of these shifts.

The residual state debt balances are being attacked by conservatives as being evidence of fiscal profligacy, but the reality is that they reflected sound health and labour market policy decisions taken at a time when uncertainty was high and no-one knew where the pandemic was going to take us.

Had the governments failed to intervene on this scale, the income losses for citizens and the negative health consequences would have been much higher than they were.

In 2018-19, net debt as a percentage of GDP for all Australian governments was 24.5 per cent.

By 2020-21, it had risen to 37.8 per cent.

By June 2024, Federal debt as a per cent of GDP was 25.7 per cent and total state debt was 11.2 per cent.

Now I don’t use that data to suggest a problem – rather to illustrate the scale of the emergency fiscal response to the health crisis.

As part of this response, the Reserve Bank of Australia (effectively part of the federal governmental machinery, even if most people mistakenly think otherwise) introduced a very large bond-buying program.

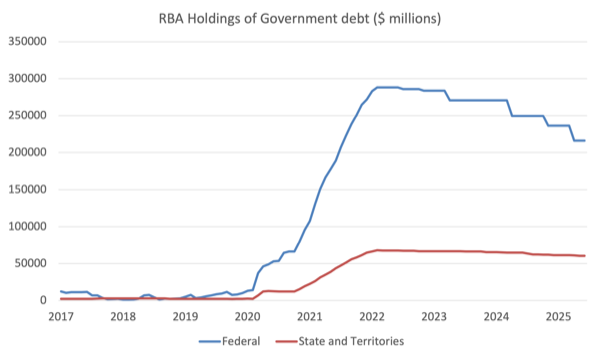

The following graph shows the shift in RBA debt holdings of federal and state debt between January 2017 and June 2025.

After February 2022, the program was tapered and the RBA has been reversing its purchases in stages.

On September 14, 2021, in the midst of the crisis, the RBA governor gave a speech – Delta, the Economy and Monetary Policy – where he said:

… keeping funding costs and lending rates low across the economy; ensuring that the financial system is very liquid; supporting household and business balance sheets; and contributing to an exchange rate that is lower than it would be otherwise. It is through these transmission mechanisms that our policies are supporting, and will continue to support, the recovery of the Australian economy over the months ahead.

The states had no option but to issue debt to fund the increases in net spending because it is a currency user.

The federal government, as the currency-issuer, faces no such financial constraint and so its voluntary practice of issuing debt to match its net fiscal spending in each period is really unnecessary.

But it is a reality given the dominance of the fiscal fictions that pretend the federal government is like a big household and financially constrained.

Challenging that fiction is not the topic of today though.

Given that reality, the RBA knew that if it entered the secondary bond market and purchased a dominant share of the new debt entering that market then it would drive yields down and insulate the economy from destructive (and greedy) speculative behaviour from the financial markets.

The reason the yields fell to very low levels is because the yield is inversely related to price (in a fixed income asset market) and the RBA pushed the demand for the bonds up, which pushed the prices up and the yields down.

The reality was that between January 2020 and February 2022, the RBA purchased the around 97 per cent of all the treasury bonds issued by the Federal government over that period.

There was a similar percentage for the shift in state-level debt purchased by the RBA, which meant that the RBA was effectively funding the shift in fiscal deficits of the currency-using state and territory governments.

Some more salient details.

The RBA earns interest on the government debt it holds.

And then transfers net profits in the form of dividends to the federal treasury department.

I call this the right pocket of government (Treasury) shifting $s into the left pocket of government (RBA) via the interest payments on the debt the RBA holds, and then the left pocket giving it back again via the dividends.

Totally ridiculous.

But for the state and territory debt there is another dimension.

The yield (interest payments) from the states to the RBA which ultimately end up in the Treasury department represent a massive fiscal (income) transfer from the state level to the federal level.

Not many people understand that and the media is totally silent about it.

Why this has become very significant is that the states are now implementing very damaging austerity because they have, as a consequence of the pandemic, what they frame as a ‘debt problem’.

And it is true that the states as currency-issuers have to find the revenue to service that debt and with the RBA hiking interest rates 11 times between May 2022 and November 2023, bond yields have risen in tandem, increasing the proportion of outlays that have to be dedicated to servicing the debt.

However, if you think about it for a second, you will realise that the ‘problem’ emerged as a consequence of the pandemic.

But think a bit more – the RBA holds most of the debt associated with that so-called debt problem.

And it could easily just type zero against that state/territory debt – that is, write it off – and no-one would blink an eyelid.

Except the ‘debt problem’ would disappear like that – a click of the keyboard and it would be gone.

I have been regularly calling for that to happen – in public presentations, in radio interviews, etc.

There was no evidence before the pandemic that the net spending of the states was out of control.

But now, the states are inflicting damaging austerity – scrapping important labour market programs, delaying essential infrastructure improvements, cancelling important projects etc – because of this ‘problem’.

So there would be a national gain if the RBA took that decision.

At a time when the federal government is looking at ways to increase productivity in the face of rising dependency ratios, having the states cutting spending in education, health, infrastructure, transport etc is not the way to go.

Victorian tax issue and the emergency services

Let’s focus on the State of Victoria for it was the worst hit in fiscal terms by the Pandemic, given its long lockdown and extensive fiscal support it provided citizens to protect their incomes, health and property during the early years of the Covid disaster.

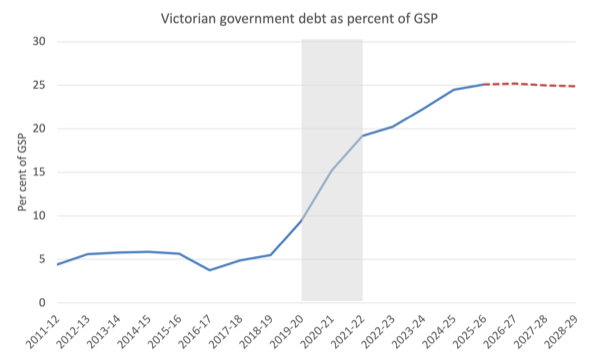

The next graph shows the Victorian state government’s outstanding debt as a per cent of Gross State Product (the state level measure of GDP).

The shaded area is the pandemic response and as noted above the RBA holds a significant proportion of the debt that was issued in that period by the Victorian government.

There is now a sense of crisis in Victoria and the government is looking at various ways of increasing revenue to reduce the outstanding public debt.

Note before the pandemic, the debt levels were low and during this period the Government was engaged in some large infrastructure projects that have been of great benefit to the citizens of that state (for example, the elimination of the dangerous railway crossings).

However, the Victorian government has also been infested for many years with the neoliberal austerity mindset – hence its fiscal surplus pre-pandemic.

One of the casualities of that mindset have been the fire and rescue services which are provided by Fire Rescue Victoria (FRV) and reflecting the high urbanisation of the state, FRV provides protection for 65.3 per cent of the Victorian population, 65 per cent of the dwellings but covers only 1.5 per cent of the geographic area of the state).

The remainder is provided by the Country Fire Authority (CFA), which is largely a volunteer service in rural areas.

Importantly, FRV provides protection for 92 per cent of the Capital Improved Value of buildings throughout the state of Victoria.

As a result of a – Black Saturday bushfires – in Victoria in early 2009, a – 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission – was established to examine how such a catastrophic event could occur (173 people died in the fires and a lot of property was lost).

One of the changes introduced after that Commission was the creation of a hypothecated revenue source for the fire services, the so-called – Fire services property levy – which was intended to provide better surety for the services and allow them to expand infrastructure and personnel.

The Victorian government noted in its most recent fiscal papers that:

Levy rates are set each year to target an amount of revenue to raise … 100 per cent of revenue from the levy goes to supporting the State’s fire services, including funding vital life-saving equipment, vehicles, firefighters, staff and volunteers, training, infrastructure, and community education.

The Victorian State Revenue Office tells us the levy has been charged annually and has two components: (a) a fixed charge that is indexed to the Consumer Price Index, meaning it is largely preserved in real terms on an annual basis; and (b) a variable charge levied on the ‘on the property’s classification and capital improved value’.

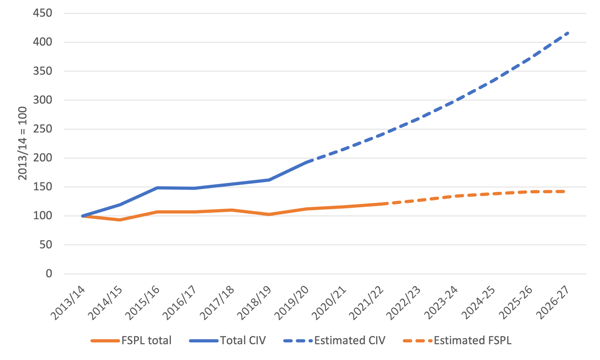

On average, the FSPL revenue grew by 3.18 per cent per annum between the years 2013-14 and 2023-24. The projected annual growth for the period 2024-25 to 2027-28 is 5.82 per cent.

The Victorian government sets the rates for the levy “to target an amount of revenue to raise” – that is, to ensure the funds required by the FRV (and CFA) are adequate.

87.5 per cent of FRV’s revenue requirements are funded by the levy to date.

The problem is that FRV still runs at a loss and is under constant pressure to funds its operations and adequately pay its staff.

For example, a qualified firefighter in Victoria has not received a pay rise since March 2021.

Over the time that has elapsed, the purchasing power of that wage has fallen by 21.4 per cent.

Relative to past trend real wage growth, the firefighter is now 27.2 per cent worse off in real terms as a result of the wage freeze and the ensuring inflation since March 2021.

FRV also has major infrastructure deficits (trucks, machinery, etc) as a result of failure to adequately fund it in the past.

So while the FSP levy might be set to generate a certain revenue, the reality is that it has been levied at rates that are too low – if the goal is to adequately fund the emergency services.

Moreover, the funding base – Capital Improved Value of Victorian properties – has grown in value.

Residential value dominates the total and between 2014 and 2024 increased by 110.2 per cent at an annual average rate of growth of 11.02 per cent.

Total CIV rose by 110.4 per cent over the period 2014 to 2024 – an annual average rate of growth of 11 per cent.

The following graph shows the growing discrepancy between FSPL revenue (actual and projected) and CIV (actual and projected).

FSPL revenue, actual and estimated and CIV actual and estimated, 2013-14 = 100

Given the significant growth in property wealth – the leviable tax base – there is huge scope for the Victorian government to ensure the fire services have sufficient financial resources without compromising other spending plans or requiring tax increases on other sources of revenue.

I say that because the Victorian government has been trying to restrict wages growth for firefighters (currently zero growth since March 2021) by appealing to is alleged ‘debt problem’.

But the fire services are funded from the hypothecated levy which is separate from consolidated revenue.

The point is that there is considerable extra capacity to raise revenue via a levy to appropriately scale the level of government support for FRV to the value of protection it provides Victorian

The other point is that the levy itself is a highly progressive source of revenue for the state government.

A – Land value tax:

… is a progressive tax, in that the tax burden falls on land owners, because land ownership is correlated with wealth and income.

It is also an ‘efficient’ tax because land is fixed and the owners enjoy increased net worth as a consequence of doing nothing.

The Victorian government also raises revenue from an assortment of taxes – such as payroll taxes, short-stay levies, etc which are not progressive in incidence.

So given that the state is a currency-user and the fire services have to be funded with revenue gained from taxation, the hypothecated fire services levy was a good option.

For progressive-minded people, such a tax is also good for equity (the rich pay more!).

Now why is this a problem now?

The State government is obsessed with austerity and has decided to lump a whole lot of additional parts of government emergency services into the levy, rename it the – Emergency Services and Volunteers Fund (ESVF) – and significantly increase the tax rates on property.

I won’t go into all the details – of which bodies have become recipients etc here.

The problem is that there is now considerable doubt that the extra capacity to raise revenue from the property levy is sufficient to meet the needs of the expanded list of recipients in the proposed Amendment without impinging on the funding capacity of the FRV and the CFA

My concern is that there will not be sufficient funds generated from the levy.

I have done a lot of detailed modelling recently on this question and I have concluded that the estimated increase in the levy revenue will not cover the estimated revenue requirements of the recipients list, which includes FRV, the major fire and rescue body in Victoria.

The details are not the issue here.

Some of the problems I see include:

- The Victorian government estimates of the required revenues of the different emergency bodies are flaky and fail to include some expensive adminstrative areas within the State Control Centre which will be funded by the ESVF.

- FRV has been running at a loss. In 2024, its total revenue and income from transactions was $1.122 million and its total expenses were $1.223 million. Once ‘other economic flows’ were included in the net result, the overall net loss was $104.2 million. Its accumulated deficit by 2024 was $247 million. There are outstanding investment shortfalls in capital equipment and FRV has not increased wages since March 2021.

- There is likely to be increased demand on the emergency services in the years ahead as a result of increased population, increased urban density, and climate change.

The problem now though is that a large coalition of unlikely collaborators including unions have united to oppose the change in the tax rates underpinning the levy.

They are framing the issue as a big tax hike by a wasteful government.

Even progressive-minded people are buying into the campaign that has just been launched largely by local governments to force the State government to scrap the tax hikes.

The local governments are rallying people claiming the State government is coercing local governments to become their ‘debt collectors’.

The problem is that the campaign is bring together an array of characters and groups that include those who are hostile to trade unions, those who are anti-government, the Right-wing elements in our society – including the more extreme end of the National Party and Liberal Party, the so-called sovereign citizen types, and more that are not the slightest bit concerned about the funding requirements of FRV and the loss of purchasing power by the firefighters.

Their motivation is to get rid of the State Labor government at his year’s election and install the deplorable Liberal/National Party as government.

Progressives are being duped into supporting this campaign and should wake up to themselves.

Conclusion

The reality is that the State government’s decision concerning the ESVF is flawed but not for the reasons this campaign is promoting.

The Government should continue to fund the additional organisations it desires to be funded from the FSPL (renamed as the ESVF) from consolidated revenue and ensure the revenue from the FSPL is adequate so that FRV can continue to provide the necessary risk protection to Victorians.

There is scope (as above) within the property tax to generate extra capacity which can be used to improve funding for equipment and personnel for FRV and the CFA.

It is the safer option for government and the communities that depend on the fire services for protection and risk abatement.

It will require a tax increase.

There is a massive shortfall of revenue available for FRV and the years of austerity have left it with a large infrastructure deficit.

And the firefighters have not had a pay rise since March 2021.

So FRV needs revenue and the property levy is a progressive tax where those with more means pay more.

If this campaign opposing the tax increase is successful then the funding crisis within FRV will deepen.

And people will die and more houses and buildings will be lost when the next fire comes through.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.