Yves here. We’ve pointed out that poor people often suffer health care costs by virtue of where they live. Rich people do not reside hard by chemical plants or sewage fields. Housing by large thoroughfares is also typically cheaper than similar dwellings further away, and for good reason. It’s not just the din. It’s also the fumes.

I suspect most readers, in comparatively well-off countries and neighborhoods, take not-too-dirty air for granted. In most of Asia, particularly the big cities, that is not at all the case. One of the reasons mask-wearing is normal here is that they are often used to combat PM2.5 pollution.

The article below shows that so-called eco-taxes not only reduced carbon emissions to a marked degree, but also improved health outcomes, particularly in low-income areas.

By Piero Basaglia, Sophie Behr, and Moritz Drupp Associate Professor for Sustainability Economics & Chair of the Sustainability Economics Group Eth Zurich; Professor of Sustainability Economics University Of Hamburg. Originally published at VoxEU

Fuel and carbon prices are typically assessed based on their effectiveness in reducing emissions, while their broader societal benefits often go overlooked. This column evaluates one of the world’s largest environmental tax experiments – Germany’s eco-tax reform – and finds that it led to sizable reductions not only in carbon emissions but also in harmful local air pollutants. Estimates reveal that two-thirds of the monetised benefits of the eco-tax stemmed from health gains linked to cleaner air and accrued disproportionately to lower-income and more polluted areas, suggesting that fuel taxes can deliver pro-poor environmental gains, even when their cost incidence is regressive.

The world faces a widening gap between climate ambition and political reality. Limiting global warming to below 2°C requires swift and ambitious global policy action (IPCC 2023). Yet public resistance to climate measures is mounting. The ‘gilets jaunes’ protests in France revealed the political sensitivity of fuel taxes (Douenne and Fabre 2022), and the re-election of Donald Trump raises fresh doubts about US commitment to global decarbonisation goals. While surveyed experts recommend that carbon prices should be much higher compared to their existing levels (Drupp et al. 2024), climate and environmental policy more broadly is under political pressure across a growing number of countries. Against this backdrop, fuel taxes remain one of the most contested, yet effective, instruments to curb emissions according to economists.

Public resistance to fuel and carbon taxes often stems from concerns over fairness, economic costs, and limited environmental benefits. Yet, public discourse and much of the economic literature (e.g. Andersson 2019, Leroutier 2022) often evaluates these taxes solely in terms of their CO₂ reductions or economic impacts, overlooking their broader societal benefits. In particular, air pollution – a leading cause of premature death worldwide with wide-reaching negative effects on well-being and productivity (e.g. Neidel et al. 2022) – is driven heavily by fossil fuel use in transport (Schlenker and Walker 2016, Knittel et al. 2016). In addition, existing research tends to emphasise average policy effects, even though carbon and fuel pricing can have substantial distributional consequences (Drupp et al. 2025, Känzig 2023). It is therefore crucial to study not only the extent to which fuel taxes can reduce a broader set of externalities, but also who actually benefits from these environmental and health improvements.

The German Eco-Tax: A Bold but Overlooked Policy Experiment

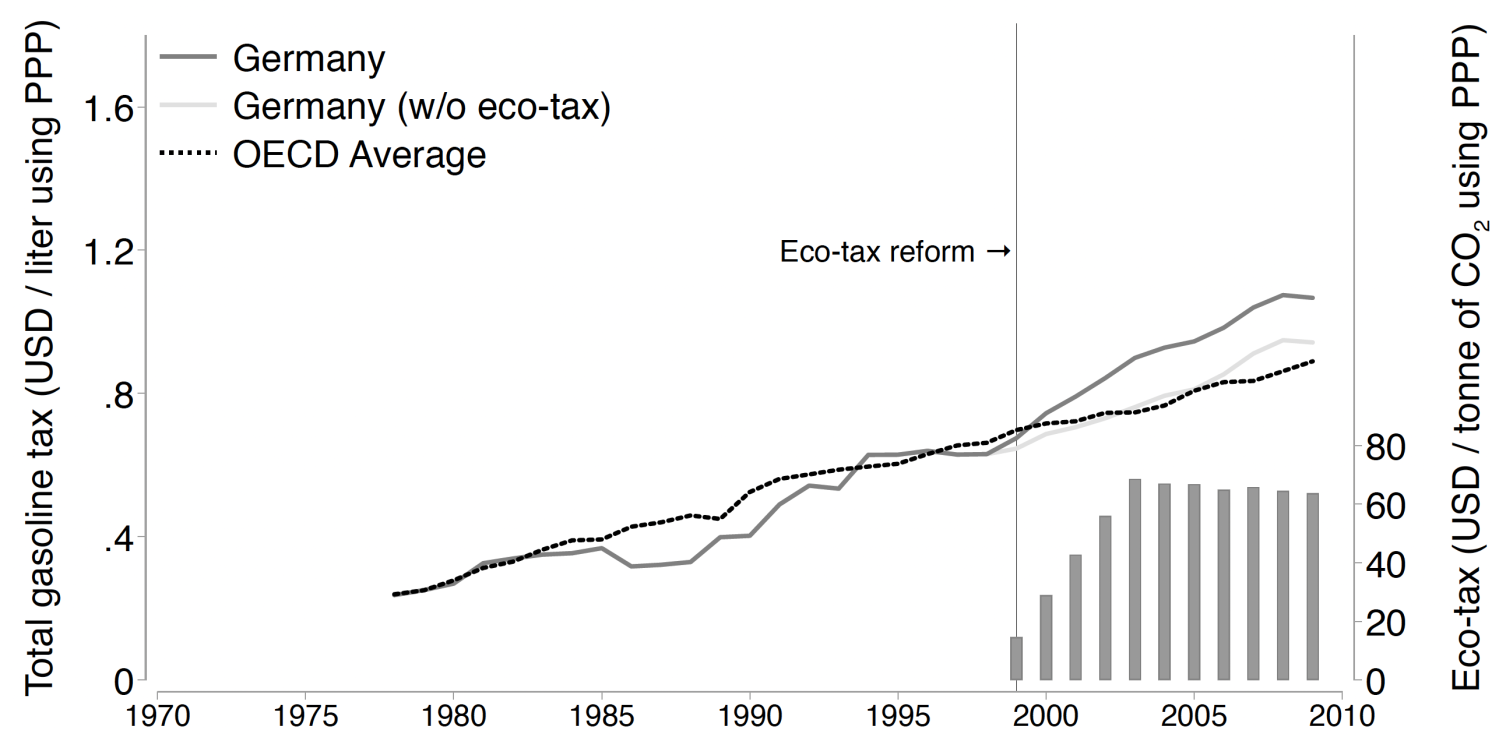

Germany’s ecological fiscal reform, commonly referred to as the eco-tax, was implemented in stages between 1999 and 2003 and increased taxes, among others, on gasoline and diesel by €0.15 per litre (see Figure 1). This amounted to an implicit carbon price of €58–€66 per tonne of CO₂, among the highest in the world at the time, second only to Sweden.

Figure 1 Evolution of transport fuel taxes in Germany and OECD average

Note: Prices are in US dollars using purchasing power parities (PPP), taken from Energy Prices and Taxes Statistics from the International Energy Agency (IEA). The eco-tax rates, expressed in terms of tonnes of CO2-equivalent, adjusted for PPP and including the value-added tax (VAT), are from Bach (2009).

Source: Basaglia et al. (2025).

The reform followed a ‘double dividend’ logic (Bach 2009). Revenues were used to reduce pension contributions, aiming to shift the tax burden from labour to pollution. Despite its scale and prominence, the eco-tax has received relatively little empirical attention compared to other European reforms. In a recent study (Basaglia et al. 2025), we revisit the German case with newly available data and methods, linking transport-related emissions, population, and socioeconomic indicators at the regional level.

Building the Counterfactual: What if Germany Hadn’t Introduced the Eco-Tax?

To evaluate the impacts of the eco-tax, we draw on the synthetic difference-in-differences (SDID) approach developed by Arkhangelsky et al. (2021). This method allows us to estimate what German emissions would have looked like in the absence of the reform by comparing trends to a weighted combination of similar European regions that were not exposed to the tax. In effect, for each of Germany’s roughly 400 districts (Kreise), we construct ‘statistical twins’ to serve as a counterfactual across a range of specifications. By comparing outcomes between actual and synthetic districts, we then isolate the causal impact of the eco-tax on emissions. We focus on the transport sector, as other targeted sectors were subject to substantial exemptions, diluting the price signal. In terms of outcomes, we focus on emissions that contribute to both global warming and local health risks, specifically carbon dioxide (CO₂), fine particulate matter (PM₂.₅), and nitrogen oxides (NOₓ).

Figure 2 European territorial grids in the estimation samples

Note: Estimation sample definitions used in the analysis. The left panel displays the 15 countries that were EU members at the time of the eco-tax reform (EU-15, light blue), alongside the current EU membership (EU-27, dark blue), which constitutes our baseline sample. Note that the UK formally left the EU in 2020. The centre panel highlights EU border regions, defined as areas either sharing a land border or with more than 50% of the population residing within 25 km of one. These regions are excluded from the Border regions model specification for robustness due to potential concerns linked to fuel tourism. The right panel shows a restricted EU sample, excluding countries that experienced major fuel tax changes. All panels use the OECD’s TL3 regional classification.

Source: Basaglia et al. (2025).

Swift and Significant Gains from Carbon Pricing

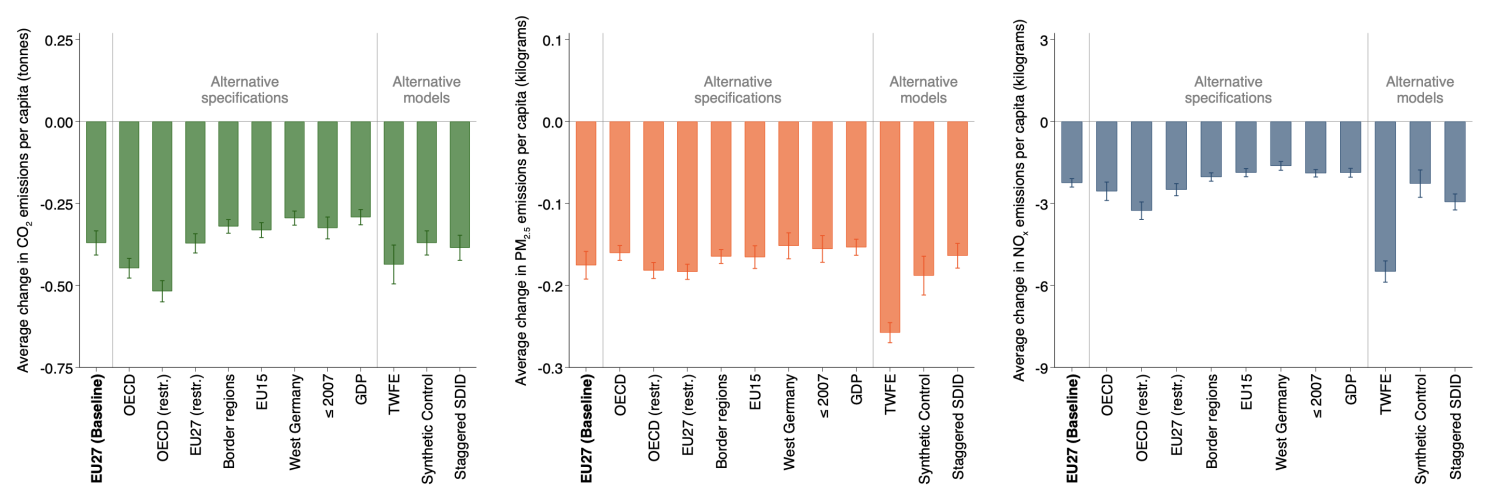

We show that the eco-tax led to a 15% reduction in transport-related CO₂ emissions per capita, a 25% reduction in PM₂.₅ emissions, and a 13% reduction in NOₓ emissions. These effects are economically sizable, and hold across multiple model specifications and leveraging different estimation samples to mitigate concerns about the impacts of (1) EU-wide macroeconomic shocks, (2) fuel tourism, or (3) concurrent fuel tax reforms in other countries.

Figure 3 Average treatment effects across specifications and models

Note: The figure plots our estimated average treatment effects on the treated (ATTs) in our baseline as well as (i) alternative specifications and (ii) alternative models with a different estimator or study design. See Basaglia et al. (2025) for more details on the different methodological approaches.

Source: Basaglia et al. (2025).

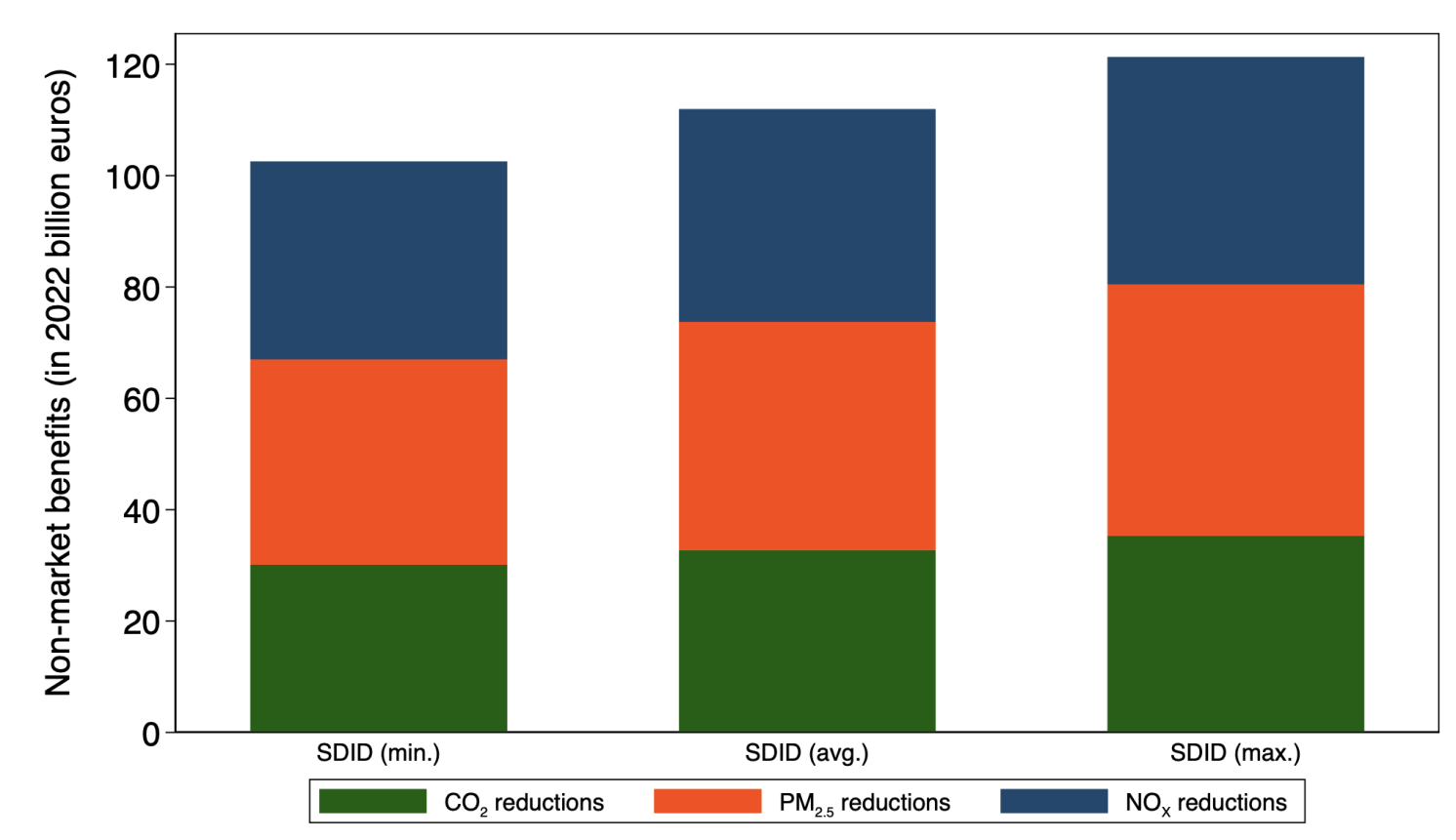

When using official damage valuations from the German Environment Agency (Umweltbundesamt 2012) at the time, the avoided external costs exceed €100 billion (in 2022 prices) over the first decade. Crucially, two-thirds of these savings stem from reductions in air pollution, rather than CO₂ alone (see Figure 4). These results challenge the common sole focus on climate benefits when evaluating fuel or carbon pricing. Air quality improvements are not only substantial, they also accrue more directly to those who shoulder the mitigation burden.

Figure 4 Reductions in climate and pollution damages due to the eco-tax

Note: The figure plots the estimated reductions in external climate and pollution damages based on estimates from the SDID estimations with minimum and maximum values corresponding to the 95% confidence intervals.

Source: Basaglia et al. (2025).

Who Benefits from Cleaner Air? Equity Effects of Fuel Taxation

Fuel taxes often raise distributional concerns, as lower-income households tend to spend a larger share of their income on energy and are more vulnerable to policy-driven price increases. Indeed, fuel pricing in Germany is slightly regressive (e.g. Jacobs et al., 2022). However, these arguments typically focus on costs, overlooking how the benefits of reduced pollution are distributed across space and income groups. To assess this, we examine the eco-tax’s effects across Germany’s districts, combining high-resolution per capita emissions data with local economic indicators, such as purchasing power per capita (see Figure 5).

We find that:

- pollution reductions and the associated health benefits were larger in lower-income districts; and

- health gains were greatest in areas with higher baseline pollution levels

This suggests that, while the eco-tax imposed modestly regressive fuel cost burdens, it generated a progressive distribution of environmental benefits. By cutting pollution most in places where it was both most harmful and most concentrated, the reform helped reduce pre-existing inequalities in environmental exposure, an equity dimension often overlooked in debates on carbon pricing across Europe. 1

Figure 5 Distribution of pollution changes and health co-benefits

Note: Panel (a) maps the distribution of the changes in PM₂.₅ per capita, while Panel (c) provides an analogue for NOₓ. Panel (b) maps purchasing power per capita in 2005 (in thousand EUR). Panels (d) and (e) combine information from Panels (a–c) and plot the reductions in PM₂.₅ and NOₓ against purchasing power using scatterplots with quadratic fits. Panel (f) shows predicted pollution reduction benefits across the purchasing power distribution, based on a quadratic regression of benefits on purchasing power and its square, under two benchmark assumptions for the income elasticity of benefits: zero and one. Panel (g) plots fitted pollution reduction benefits along baseline PM₂.₅ pollution deciles (assuming an income elasticity of zero, following German Environment Agency guidance), disaggregated by whether districts are classified as urban, intermediate, or rural.

Source: Basaglia et al. (2025).

How Did the Eco-Tax Work? Behavioural Responses and Trade-Offs

A second key finding of our study relates to the behavioural response to the eco-tax. Using additional fuel consumption data and cross-country comparisons, we estimate that the demand response to tax increases was 3–5 times larger than the response to equivalent market-driven price changes. This aligns with prior findings from the US and Sweden (Li et al. 2014, Andersson 2019), which suggest that taxes are more visible, durable, and predictable and therefore more likely to influence consumer behaviour than, for instance, fluctuations in global oil market prices.

This insight is of high policy relevance. Many governments rely on historical data linking fuel consumption to market price fluctuations when assessing the likely effects of proposed carbon pricing. These estimates are often used to forecast emissions reductions or cost burdens when debating policy adoption. Our findings and related prior research imply that this approach can largely underestimate the real impact of tax-induced price hikes, particularly if it fails to account for the stronger behavioural response that arises from the salience and credibility of tax changes. In short, we argue that how prices changed matters perhaps as much as by how much.

We also look at how different fuels contributed to the reductions. Most of the CO₂ decline came from reduced gasoline use, in part because some drivers switched to diesel, which emits less CO₂ per litre. Yet, the drop in harmful air pollutants like PM₂.₅ and NOₓ was mainly due to lower diesel consumption. This reveals an important trade-off: while diesel is more climate-efficient, it produces more air pollution. Policies that focus only on reducing the carbon content of fuels, without considering pollution, may unintentionally incentivise a shift toward diesel. If not carefully designed, such policies risk worsening local pollution even as they reduce carbon.

What policymakers should take away from the German experience

Our findings have four key implications:

- Environmental or health co-benefits are sizable and must be included in policy appraisals. Focusing only on CO₂ misses most of the welfare gains from fuel taxation.

- Fuel taxes are more effective than commonly assumed, likely due to their salience, longer persistence and behavioural impacts.

- Distributional assessments should consider benefits, not just costs. In this case, low-income and high-pollution areas gained most from improved air quality.

- Design matters. Policymakers should account for substitution effects and aim for comprehensive taxation that aligns climate and broader sustainability goals.

Fuel Pricing Works – but the Full Societal Value of Pricing Schemes Is Often Overlooked

Fuel and carbon taxes remain politically contentious, but dismissing them risks sidelining one of the most effective tools available for cutting emissions and improving public health. The German eco-tax experience demonstrates that well-designed fuel taxation can simultaneously advance climate goals, raise public revenue, and deliver substantial health benefits – particularly in more polluted and economically vulnerable areas. As governments grapple with the challenge of decarbonising transport and cleaning up urban air, recognising these broader co-benefits is essential for informed, balanced policy debate and for building the public support that ambitious climate action ultimately requires. This does not only apply to taxation but is also relevant for other forms of regulation. Indeed, recent research has, for instance, documented that the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) has likely generated sizable health co-benefits, and the cap-and trade scheme in California has likewise led to a substantial reduction in air pollutants and reduced environmental justice gaps (Hernandez-Cortes and Meng 2023). This offers important lessons for the design of price stability mechanisms intended to balance distributional implications for the EU ETS 2, which will expand the scope of carbon pricing to include the transport and heating sectors in 2027.

See original post for references