Many people have seen pictures of the so-called “Rainbow Mountains” of China on Instagram or some other social media platform. They know they look cool, but don’t know that visiting this landmark can be an introduction to a fascinating and historic corner of China in the Province of Gansu, known as the Hexi (“hə-SHEE”) Corridor.

This story follows my route west from Lanzhou through the Hexi Corridor to Dunhuang, along the ancient Silk Road. Think high-speed trains instead of caravans, rainbow-striped ridgelines, Buddhist caves, and desert winds. I took this tour as a guest of the China Tourism board.

General Wei Qing – Gansu Provincial Museum in Lanzhou

A Bit of History

Emperor Wu of Han had a problem in the late 2nd century BCE because the northwest was a persistent headache. By the 120s BCE, Xiongnu raids (or the Huns, as the Movie Mulan called them) were cutting into tax revenues, threatening farms and towns, and capable of severing the Silk Road just as long-distance trade was becoming lucrative. China also needed strong warhorses from the steppe and Central Asia, which meant securing safe, direct routes rather than relying on hostile intermediaries.

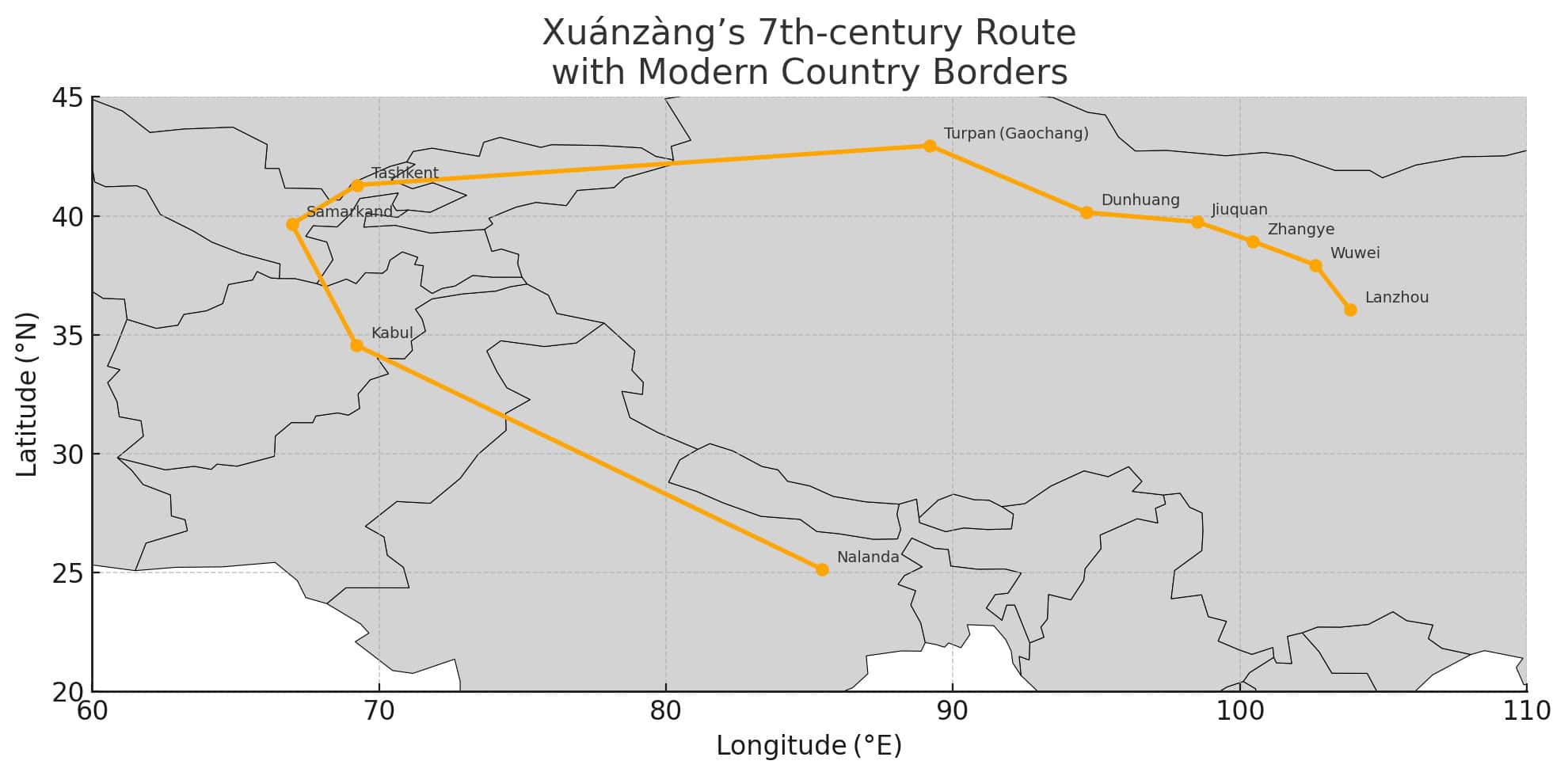

Earlier reconnaissance by Zhang Qian in the 130s BCE showed that alliances and commerce to the west were possible, but only if the narrow Hexi Corridor was held end to end. So in 121 BCE, Emperor Wu sent generals Wei Qing and Huo Qubing to break Xiongnu control, then locked in the gains over the next decade by extending walls and garrisons, planting state farms to feed them, and founding the four cities of Hexi at Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan, and Dunhuang. By about 111 BCE, the route from Lanzhou to Dunhuang was secure, and Silk Road caravans could pass under Han protection.

Goods and ideas flowed through the Silk Road in and out of China for the next 1400 years. Trade waxed and waned depending on who was in charge in China, but this trade route gave the West silk, and later paper and gunpowder. It gave China gold and gems, Buddhism, horses and camels, and glassware.

Lanzhou: Yellow River City

Lanzhou is the capital of the Gansu region, which includes this historic corridor. It is served by the large, new and thoroughly modern Lanzhou airport. The airport was built with growth in mind and is probably 2-3x the size it would need to be for its current air traffic.

The Yellow River

The Yellow River Valley is where China started, and the city of Lanzhou is one of the major cities on the river. The city itself is 2,100 years old and boasts the first bridge over the river, which was not built until 1909 with the help of German engineers.

lamb skin rafts

The boardwalk along the Yellow River by the Iron Bridge are crowded with tourists, mainly from China. If you want to experience how people used to cross the river, outfitters will put you on a raft that is supported by inflated lamb skins to drift down the river. Your return trip will be by a much less historic means, a speedboat.

Journey to the West

As you stroll along the river, watch for a statue of the Mother River that celebrates how central this muddy river was to the start of the Chinese civilization, and a statue called “Journey to the West” that celebrates the journey of the Tang Dynasty monk Xuánzàng , who traveled from Lanzhou to India via the circuitous route of the Silk Road to bring back Buddhist texts.

Gansu Provincial Museum in Lanzhou

At the Gansu Provincial Museum in Lanzhou, the Silk Road galleries frame that story with Han-era finds from the corridor, including the museum’s emblematic treasure, the Eastern Han bronze “Flying Horse of Gansu,” excavated at Wuwei along the route and now a national symbol; together these exhibits show how Wei Qing’s victories helped transform Gansu into China’s overland bridge to Central Asia. English tours are available for the museum.

Markets and Local Cuisine

Don’t leave Langhou without stopping at a tea house for the renowned eight-treasure tea, which includes:

- Tea: green (often jasmine) or black/pu-erh

- Goji berries (wolfberries)

- Red jujube (Chinese dates), sliced

- Dried longan

- Chrysanthemum flowers

- Raisins

- Candied tangerine peel (chenpi)

- Rock sugar (or crystal sugar)

You drink the tea with two hands, using your other hand to hold a lid that keeps these ingredients in your cup.

Trade in Langhou did not end with the decline of the Silk Road. By day, the Taohai Market in the Chengguan District is piled high with spices, teas, produce, and photogenic stacks of breads. By night, we drifted through one of Lanzhou’s four night markets for skewers, pastries, and people-watching.

Lanzhou is known for its handle-pulled noodle soup, which is available at both inexpensive and fancier restaurants in the city. We took a lesson in making noodles at the city’s “noodle museum,” where a master creates perfectly even strands of hand-pulled beef noodles in seconds.

Riding the Hexi Corridor by high-speed rail

From Lanzhou onward, we traveled by China’s high-speed trains. Train tickets can only be booked 2 weeks in advance, so plan accordingly. The trains are modern and efficient. At one short transfer, a conductor literally pushed a car full of passengers off and the next group on to keep the schedule tight. This is a far cry from the night train to Xi’an that I took on a previous visit to China, although I did note that not all the train cars that I was on had western toilets.

Zhangye: Grottos and Rainbow Mountains

Mati Temple Grottoes

On the flank of a sandstone cliff near Zhangye, the Mati Temple Grottoes hide in plain sight. Stairwells thread through the rock to small cave shrines cut over centuries. The oldest sections likely date to the fifth or sixth century. Ming-era additions arrived a millennium later. Some original images were replaced during the Qing dynasty, yet older murals remain in the backs of caves if you look closely.

One of the smaller caves has what looks like an imprint of a horseshoe, which is said to be created by a celestial horse. This print gave the area the name “Horseshoe Temple,” which is the meaning of Mati.

These are not the most interesting Buddhist caves that you will see in this region, but they are a good introduction.

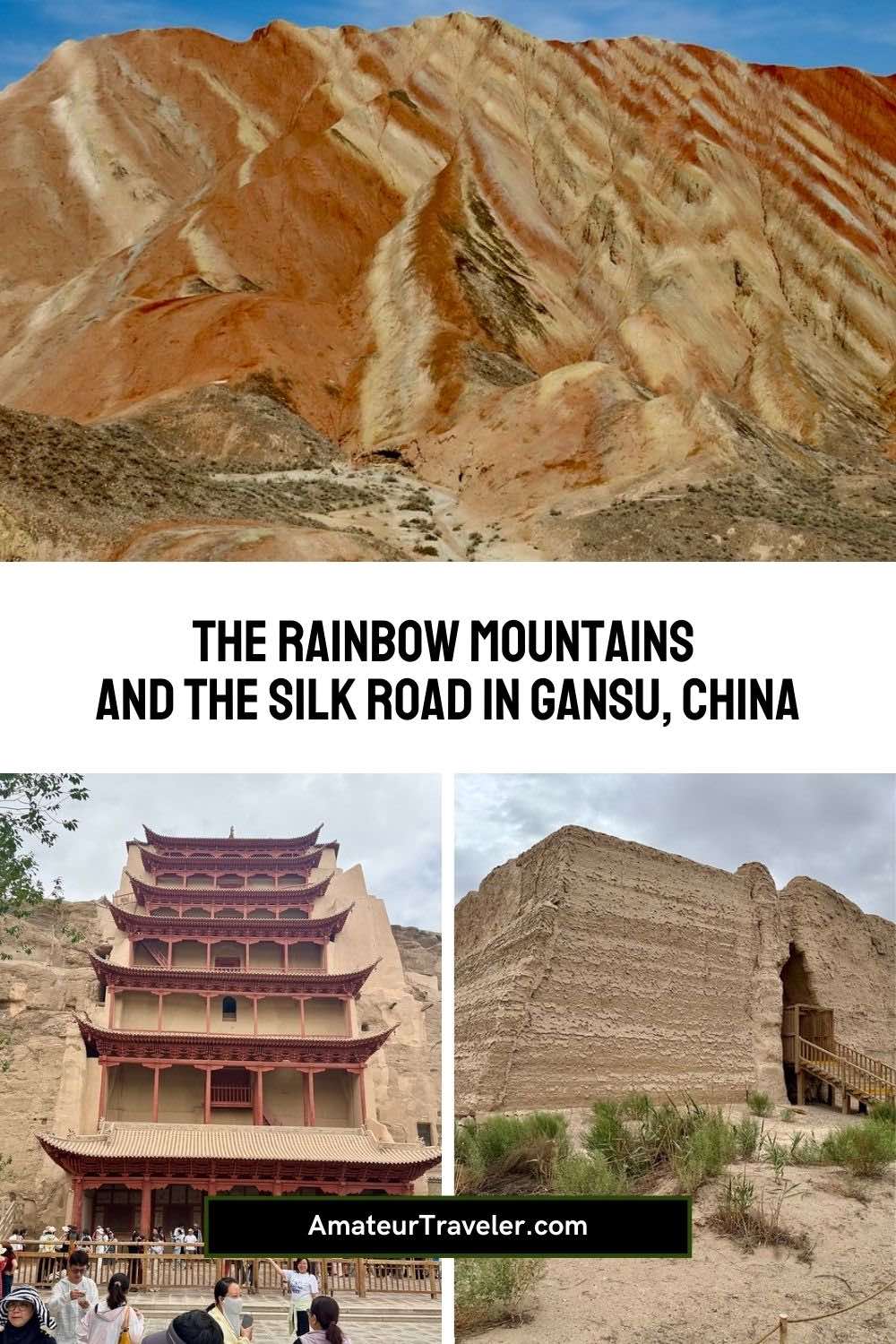

Zhangye Danxia Geopark, the “Rainbow Mountains”

This is the photo that probably drew you to Gansu. The Zhangye Danxia Landform Geological Park rolls out ridgelines striped in reds, yellows, and grays, as if a painter tilted the canvas to a 45-degree angle. Those colors come from layers of iron-rich and iron-poor sediments laid down over time, then uplifted and weathered into the patterns you see today. It is as vivid in person as it looks online. We were told colors pop even more just after rain.

We had the park’s VIP route, which costs more than the regular loops but lets a small group venture deeper and stop at three areas. Two stops deliver classic viewpoints over the striped hills. At the second stop, there is a hike to a higher viewpoint for the more fit and adventurous.

The third feels almost like a pocket version of Bryce Canyon, with gray hoodoo formations where wind and water carved finer shapes. It is only available to those who take the VIP tour. Each of the formations has been given a name. Some of the more memorable names were “Boya playing Heptachord”, “The Drunken Poetic Genius”, and “Old Turtle Asking about Longevity”.

The regular route runs about twelve dollars, the VIP closer to fifty, and both use park buses in a timed loop system.

We had a tour guide, but did not run into any tour guides who spoke English at the park. For a more unusual way to see the park, we saw helicopter tours and ultralight aircraft tours.

Dunhuang: Oasis, Grottoes, and Desert

The train west to Dunhuang runs past long fences of wind turbines and miles of flat gravel plain. When green appears, it appears all at once. This is an oasis town in the truest sense. Downtown feels new because the city was abandoned during the Ming era and only reestablished during the Qing about a century ago. We celebrated our arrival with a traditional lamb dinner, then wandered a permanent night market under trees strung with lights.

The Mogao Grottoes

The Mogao Grottoes, just outside Dunhuang at the edge of the Gobi Desert, are a breathtaking testament to the Silk Road’s cultural and religious exchange. Carved into a sandstone cliff between the 4th and 14th centuries, the site contains 735 caves that hold exquisite Buddhist murals and statues. The visit begins with two short films, one a historical overview, the other an IMAX immersion.

They explain how caravans brought Buddhism from India along this route, inspiring generations of patrons to sponsor cave art as an act of devotion. Our English-speaking guide then led us through eight caves, each revealing a different slice of history: from the giant seated Buddha of Cave 96 that forces you to crane your neck upward, to the reclining Buddha in Cave 332 flanked by past, present, and future Buddhas.

One of the most intriguing parts of the visit was the story of the Library Cave, Cave 17, discovered in 1900 by a Taoist monk clearing sand. Inside were thousands of manuscripts, some dating back to the 4th century, hidden, perhaps to protect them from invading Mongols, until their rediscovery. Sadly, many of these treasures now reside in the British Museum and Paris, taken by early 20th-century explorers such as Aurel Stein and Paul Pelliot.

The artistry that remains in Dunhuang is staggering: 45,000 square meters of murals, statues alive with fluid drapery folds, and donor portraits that give a human face to the people who made this art possible.

Photography is forbidden inside the actual caves, but the on-site museum offers detailed, life-size reproductions of some of the most ornate interiors.

Singing Sand Dunes and Crescent Lake

We had planned a camel ride at the Singing Sand Dunes, but a sandstorm closed the area. You can see the tall sand dunes from town. The classic crescent-shaped oasis sits just beyond. We had to settle for photos and a promise to return.

Music and Dance of Dunhuang

“Music and Dance of Dunhuang” is an evening performance that transforms Dunhuang’s Silk Road history into an immersive theatrical experience. Performed several times daily, the show blends dance, acrobatics, live music, and elaborate staging to evoke the art and stories found in the Mogao Grottoes.

The production begins in an unconventional way: audience members are guided through a series of themed spaces rather than sitting down immediately. In the opening hall, artificial rain falls as performers move among the crowd, drawing you into the narrative. From there, you follow the cast into other rooms, at one point encountering leaping “demons” in a dimly lit chamber, before arriving in the main theater.

Once in the main performance hall, the scale widens to a Cirque du Soleil–style spectacle, complete with aerialists, jugglers, and dancers in flowing costumes inspired by the grotto murals. The choreography and set design echo the painted scenes of celestial musicians and flying apsaras that appear in the cave art, while the music incorporates both traditional Chinese instruments and modern arrangements. Without relying on spoken dialogue, the show communicates its story visually and musically, making it accessible to both Mandarin and non-Mandarin speakers.

Yardang Geopark

About two hours north of Dunhuang, the landscape dissolves into a vast, wind-scoured expanse that feels almost otherworldly—this is Dunhuang Yardang National Geopark, part of the UNESCO Global Geoparks network. The term “yardang” refers to elongated ridges of compacted sand and rock, carved over centuries by wind erosion. Here, thousands of these formations stretch across the Gobi Desert in a scene so barren and dramatic it’s earned the nickname Yadan Devil City. Standing among the formations, you can hear the wind whistle through narrow gaps, producing the eerie, high-pitched sounds that inspired the name.

The park’s infrastructure is well developed: visitors tour on a loop bus that stops at designated viewpoints, each with just enough time to explore and photograph before reboarding.

The formations themselves ignite the imagination. Many are named for what they resemble—ships, animals, even yurts—inviting visitors to spot shapes in the sandstone much like one would in cloud formations. One highlight is “the Armada,” a series of parallel ridges lined up like a fleet at sea, created where wind has scoured away softer material between harder layers. Colors here are subtler than Zhangye’s Rainbow Mountains, with soft yellows, tans, and grays that shift in the changing light.

The sheer emptiness surrounding the park makes the shapes seem even more striking, rising from a flat desert plain that stretches to the horizon. For the adventurous, optional add-on excursions by jeep, dune buggy, or open-air bus venture deeper into the park for more intimate encounters with the formations.

Scenes from Disney’s live-action Mulan were shot here, and it’s easy to see why—the setting evokes the vast, untamed edges of empire. Whether you explore only the main loop or opt for an off-road excursion, Yardang offers a chance to experience the stark beauty of the Gobi in one of its most iconic forms.

Jade Gate

Yumen Pass, or the “Jade Gate,” sits about halfway between Dunhuang and Yardang Geopark, marking one of the most important checkpoints on the ancient Silk Road. Established during the Han Dynasty in the 2nd century BCE, it took its name from the jade that caravans carried eastward from Central Asia.

The pass was part of a larger defensive network along the Hexi Corridor, anchored by the original Han-era Great Wall built from tamped earth and straw. Unlike the stone and brick Ming Dynasty walls near Beijing, these fortifications are low, weathered, and earthen, yet remarkably well preserved given their 2,000-year age.

Caravans once passed just south of these walls, while the nomadic Xiongnu roamed to the north, making the pass both a gateway and a guard post for traders, soldiers, and envoys traveling between China and the West.

Today, visitors tour the site via shuttle bus, stopping at several points of interest. One viewpoint offers a close look at the eroded wall and a surviving guard tower; another features the remains of a large earthen fortress that also served as a granary to supply frontier garrisons. A smaller outpost, Fang Pan Castle, rounds out the circuit, set against the surprising greenery of the nearby Shule River oasis. Standing here, it’s easy to imagine the mix of relief and anticipation that travelers must have felt after crossing hundreds of miles of desert to reach this narrow lifeline of water, shelter, and protection.

What we skipped and what you might add

Gansu’s westbound arc offers more than any one trip can hold. We passed on Wuwei and Jiayuguan due to time and rail routing. Wuwei is famous for the bronze Galloping Horse you can see in Lanzhou’s museum. Jiayuguan preserves the western end of the Ming Dynasty’s western Great Wall stronghold. If you have a spare day, both make sense. Wuwei is not yet connected by the same high-speed line.

How to Plan a Similar Trip

You can find small group tours of this area on Tour Radar: Gansu Tours. The director of the Los Angeles office of the China Tourism Board also recommends this tour vendor for planning trips to Gansu: China Tour.

Where We Stayed

Here’s a handy summary of where we stayed during our Silk Road route in Gansu, with brief impressions and convenient booking links:

- Lanzhou – Lanzhou Olympic Sports Guozi Hotel: Comfortable and modern, great location with thoughtful touches (even a robot delivery service introduced us to tech-savvy China).

- Zhangye – Zhangye Hotel: A lovely hotel, a bit out of town, in a quiet park with a pond.

- Dunhuang – Huaxia Hotel: You have to love a hotel that provides a hot water foot bath after your trip to the desert, but it’s not the newest hotel in the area and would benefit from adding non-smoking rooms.

Final Thoughts

Traveling the Silk Road across Gansu is a journey through layers of history, culture, and landscape that few places can match. From Lanzhou’s bustling riverfront and steaming bowls of hand-pulled noodles to Zhangye’s technicolor Rainbow Mountains and Dunhuang’s awe-inspiring Mogao Grottoes, each stop offers its own window into China’s past and present. High-speed trains link ancient outposts, desert winds still sculpt the Yardang formations, and sites like the Jade Gate remind you that this was once a true frontier.

Gansu blends preservation with accessibility. You can stand where Han generals defended the empire, then be back in a modern hotel by nightfall. It’s a region that rewards curiosity, invites slow exploration, and leaves you with the sense that you’ve walked, however briefly, in the footsteps of caravans, monks, and explorers who shaped the story of East-West exchange.

To learn more about my journey, listen to the podcasts Travel the Silk Road in Gansu, China – Amateur Traveler Episode 955 and Travel to China (Beijing and Gannan) – Amateur Traveler Episode 954.

This post is about part of a 2-week trip to China sponsored by the Chinese Tourism Board. I am grateful for the trip, but all opinions expressed are my own.