Yves here. We’re featuring this post more as a critical thinking exercise rather than for the findings of the study posted below, although they are also of interest. As you’ll see, a study performed using 2000 to 2005 data in Germany found that workers who’d lost their jobs didn’t fare as bad as average outcomes suggested, since some were hit hard, while 25% had reached higher of pay in five years.

To which I say “Huh?”

First, even the relatively advantaged 25% would often suffered loss of income and presumably relative savings over the part if not all of the five year period. To reach better conclusions, you’d need to estimate lifetime earnings and see if they had prospects of coming out net ahead, based on the period of no/lower income and to what degree the later, higher earnings more than compensated for that.

Second, 25% better off still confirms a grim picture, that 75% were worse off on a long-term basis.

Third, the study time frame happened to occur during a period of strong growth in Germany. From the World Bank:

Fourth, German collective bargaining representation has fallen since 2000, which generally suggests a weakening of labor rights (readers who have more knowledge of the situation in Germany are encouraged to speak up; a quick search was not terribly informative). A European Union Trade Council report in 2020 found that the percentage of German workers covered by collective bargaining agreements had fallen by 14% to 54%, below the EU average of 61%. So Germany is far from the worker paradise that some assume it to be. The EU states with much higher collective bargaining levels: Denmark, Finland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Italy, Austria, Netherlands, Finland, Belgium, France, Luxembourg, Sweden. Austria leads the pack at 98%.

Mind you, what bothers me is not the findings (the findings are the findings, after all) but the spin, staring with the dishonest labeling of job loss as “job displacement”. “Job displacement” connotes that all of those fired eventually find new employment, when some never do, or at least not at any kind of reliable work.

In addition, it’s one thing to say, “Earlier information on this topic might not be as terrible as it appeared” as opposed to the shading taken here, that unevenly distributed long-term results from job loss means they are not a biggie. Arguably less bad is still bad.

An example of what I mean:

Interestingly, both groups exhibit similar overall mobility – changing industries, occupations, and regions multiple times – but adjusters make decisive moves immediately after displacement, while casualties experience delayed and unstable transitions.

So it is entirely the worker’s fault if they do not land well. The authors’ posture is that the laggards had not acted “decisively” enough.

Now admittedly, there likely were some job losers who were shocked and arguably took more time than was optimal before getting serious about securing new employment. But from observing some unceremonious exits, how fast one lands is to a significant degree a function of luck and the utility of one’s personal networks.

By Eric Hanushek, Paul and Jean Hanna Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution Stanford University; Simon Janssen, Senior Researcher German Institute for Employment Research (IAB), and Jacob D Light. Originally published at VoxEU

Decades of research have confirmed that job displacement causes significant and persistent earnings losses. This column presents new evidence from workers displaced during firm closures in West Germany between 2000 and 2005 which suggests that these losses are in fact much more heterogeneous than previously documented, and that the large average losses documented in previous work are heavily influenced by a minority of workers who experience catastrophic earnings declines.

A recurrent and urgent policy debate revolves around the long-term consequences workers face after job displacement events like firm closures or mass layoffs. Historically, studies have shown that such displacements trigger substantial and persistent earnings losses for affected workers. An extensive literature – dating back to Jacobson et al. (1993) and including influential recent studies by Davis and von Wachter (2011) for the U.S. and Schmieder et al. (2023) for Germany – documents persistent earnings losses of 15-25% following displacement, with older and less-educated workers disproportionately affected.

Much of this literature, however, has concentrated on average effects within and across groups of different workers, leaving a significant gap in our understanding of the distribution and heterogeneity of these losses among workers. In a recent paper (Hanushek et al. 2025), we use new empirical methods and comprehensive administrative data from Germany to characterise the full distribution of displaced workers’ earnings losses. Our findings suggest that the conventional narrative about displacement – centred on average losses – obscures significant differences in how workers adjust after losing their jobs and masks the fact that roughly a quarter of displaced workers come out ahead after five years.

The Skewed Distribution of Earnings Losses

We examine workers displaced from all firm closures in West Germany between 2000 and 2005. Our analysis employs a novel combination of matching and synthetic control methods at the individual worker level, which enables us to capture the full distribution of displacement losses rather than just average effects.

Our central finding is that the distribution of earnings losses is highly skewed, meaning that focusing solely on average outcomes gives an incomplete and potentially misleading view of workers’ actual experiences. The large average losses documented in previous work are heavily influenced by a minority of workers who experience catastrophic earnings declines. In fact, the modal worker’s cumulative earnings loss over five years amounts to just three months of pre-closure earnings – a significant but manageable reduction. A relatively large number of displaced workers earn even more than comparable non-displaced workers following displacement. This finding is consistent with Farber’s (2017) finding that many displaced US workers quickly secure better-paying jobs.

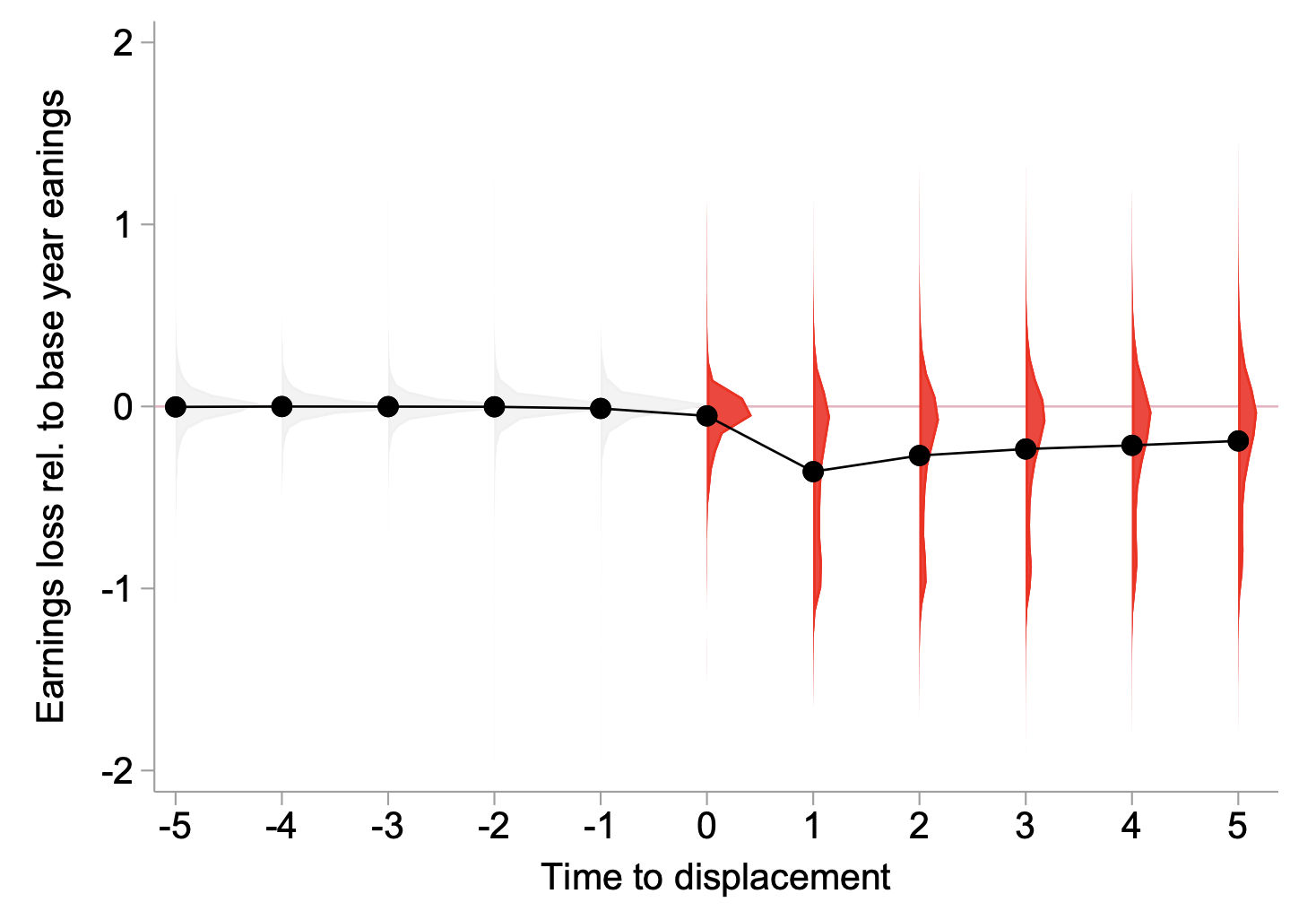

Figure 1 illustrates the point graphically; the dots plot mean earnings differences between displaced and a comparable group of non-displaced workers in the years before and after the displacement, while the grey/red shaded regions plot the full distributions. While the dots demonstrate a steep and persistent decline in earnings for the average displaced worker, the distribution of these losses is quite wide. Large losses are concentrated among a relatively small number of workers and many workers experience little disruption, or even earn more than would have been expected absent the displacement.

Figure 1 Distribution of relative earnings losses after firm closure

Notes: The figure displays the distribution of displaced workers’ earnings losses throughout a period of five years before until five years after a firm closure. The earnings losses are measured relative to the individual worker’s average earnings in the three years before the displacement. The dots represent the mean earnings losses for each period. The shaded areas represent the distribution of the displaced workers’ earnings loss estimates.

Source: IEB.

Limited Predictive Power of Observable Characteristics

Previous studies document differences in displacement effects for workers from different demographic groups – older workers, women, and those with lower educational attainment typically suffer larger average losses. This literature also highlights the loss of firm-specific wage premia as a primary driver of losses following displacement (e.g. Lachowska et al. 2020). Our findings align with these average patterns but also highlight their limited explanatory power: observable worker and firm characteristics explain less than 20% of the total variance in displaced workers’ earnings losses.

Even among displaced workers from the same firm, in identical roles, and with similar demographic characteristics, we find strikingly divergent outcomes. Some quickly transition to new employment with stable or even improved wages, while others face protracted unemployment or severe wage penalties. This within-group heterogeneity poses challenges for policymakers designing unemployment assistance programmes, as targeting based on worker or firm characteristics alone may fail to direct resources to those who most need them. Instead, ex ante unobservable factors and luck seem to drive a substantial portion of the heterogeneity in workers’ post-displacement outcomes.

Distinguishing ‘Adjusters’ From ‘Casualties’

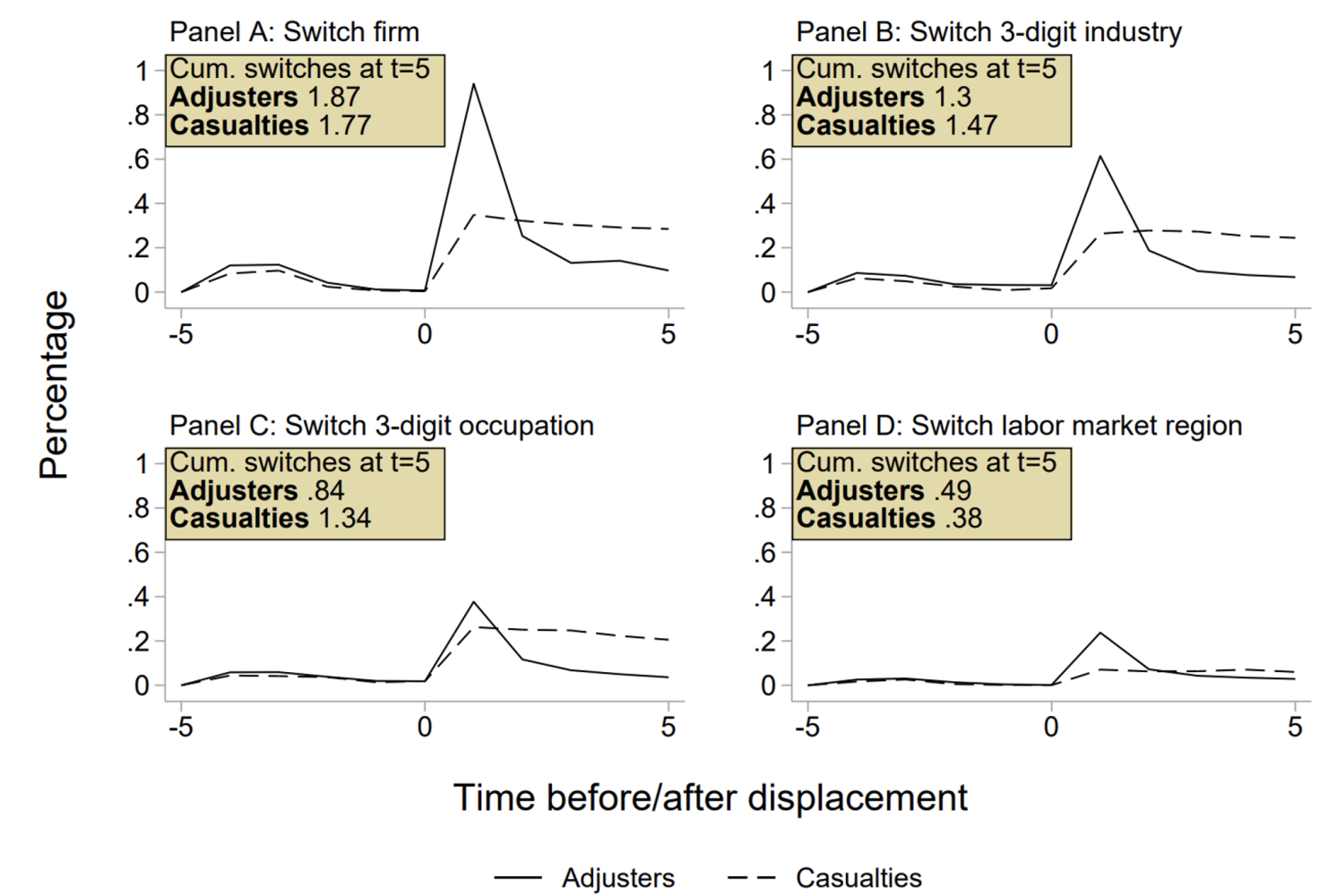

To further illustrate the heterogeneity in displacement outcomes, we classify workers into two groups based on the severity of their losses: ‘adjusters’ (lowest quartile of losses) and ‘casualties’ (highest quartile of losses). Although these groups are similar demographically, their post-displacement labour market trajectories differ profoundly.

Adjusters react quickly. They switch occupations, industries, and even regions immediately after displacement. Adjusters stabilize quickly in these new positions and typically regain or exceed their pre-displacement wage levels within five years. In contrast, casualties struggle to regain stable employment, experiencing prolonged unemployment and unstable, low-paying jobs. Figure 2 documents this divergence across a variety of different margins of adjustment:

Figure 2 Fraction of workers who switch firm, industry, occupation, and region after firm closure

Notes: The figure compares the frequency of different margins of response to firm closure for Adjusters and Casualties around firm closures (time = 0). All changes are conditional on being employed during that year. The boxes in the upper-left corner summarize the average cumulative number of changes during the five-year period post-displacement for each group.

Source: IEB.

Interestingly, both groups exhibit similar overall mobility – changing industries, occupations, and regions multiple times – but adjusters make decisive moves immediately after displacement, while casualties experience delayed and unstable transitions. This finding echoes recent research by Fallick et al. (2025), who emphasise the role of extended unemployment spells in exacerbating displacement losses. Consistent with work by Minaya et al. (2023), we do not see large numbers of workers pursuing continuing education as a means of adjusting to the displacement.

The effect of firm-specific factors is also nuanced. Casualties go to lower paying firms and receive wages significantly below average in these firms. Adjusters go to slightly higher paying firms but then see wages significantly above the average worker in these firms.

Conclusion

Decades of research have confirmed that job displacement causes significant and persistent earnings losses. However, our new evidence suggests these losses are much more heterogeneous than previously documented. By focusing on average effects, researchers and policymakers may miss the substantial variation in displacement experiences among observably similar workers. Navigating a layoff involves personal circumstance, resilience, and luck. These unpredictable factors complicate the design of effective assistance programmes, as it remains difficult to anticipate who will adjust successfully and who will endure lasting disruption.

See original post for references