Yves here. This article from Global GeoPolitics documents in detail how key African states such as Nigeria, Kenya, and Rwanda have unwittingly and severely compromised their sovereignity via entering into agreements for the use of citizen tax and health data with foreign providers. They go beyond technical assistance and represent the transfer of strategic assets.

From an e-mailed overview:

Drawing on independent analysts, legal scholars, and historical precedent, the analysis shows how data now performs the same function taxation and population registers once served under colonial rule. The piece sets out the long-term consequences for sovereignty, security, and democratic accountability, and explains why these agreements mark a structural turning point rather than isolated policy errors.

The risks of these decisions become clearer when placed against recent evidence of how the same data firms who will use this data operate in active conflict zones. An Associated Press investigation confirmed that artificial intelligence systems developed by Microsoft and OpenAI were integrated into Israeli military targeting operations in Gaza and Lebanon, marking one of the first documented uses of commercial AI in live warfare. Those systems relied on large-scale data ingestion, predictive modelling, and pattern analysis drawn from civilian information streams. The outcome demonstrated how population data, once absorbed into security architectures, can be repurposed for surveillance, targeting, and lethal decision-making without public oversight. African governments transferring tax, health, and biometric data to foreign partners are placing similarly comprehensive population profiles into ecosystems already proven capable of military application. Control over such data determines not only economic planning or healthcare delivery, but also how populations can be mapped, categorised, and acted upon during political crises, civil unrest, or external intervention. The Gaza precedent shows that assurances of benign use hold little weight once data enters integrated intelligence systems governed beyond the reach of affected citizens.

In addition, a widespread view is that China has made such strong economic inroads into Africa so as to greatly weaken US and European influence. The generally unrecognized role of the West in being able to see and mine large amounts of sensitive information of citizens in major African nation suggests that the US and the old colonial powers still have a lot of sway.

Originally published by Global GeoPolitics

Data colonialism on the African continent has moved from abstraction into formal state policy through binding agreements signed without public consent, parliamentary scrutiny, or meaningful legal protection for citizens. Nigeria’s memorandum of understanding with France on tax administration data, alongside healthcare data-sharing agreements signed by Kenya and Rwanda with United States agencies, reflects a pattern of external control over sovereign information systems. These arrangements represent a transfer of strategic national assets rather than technical cooperation. Historical experience across former colonies shows that control over taxation, health records, and population data has always preceded deeper forms of domination, even when formal sovereignty remained intact.

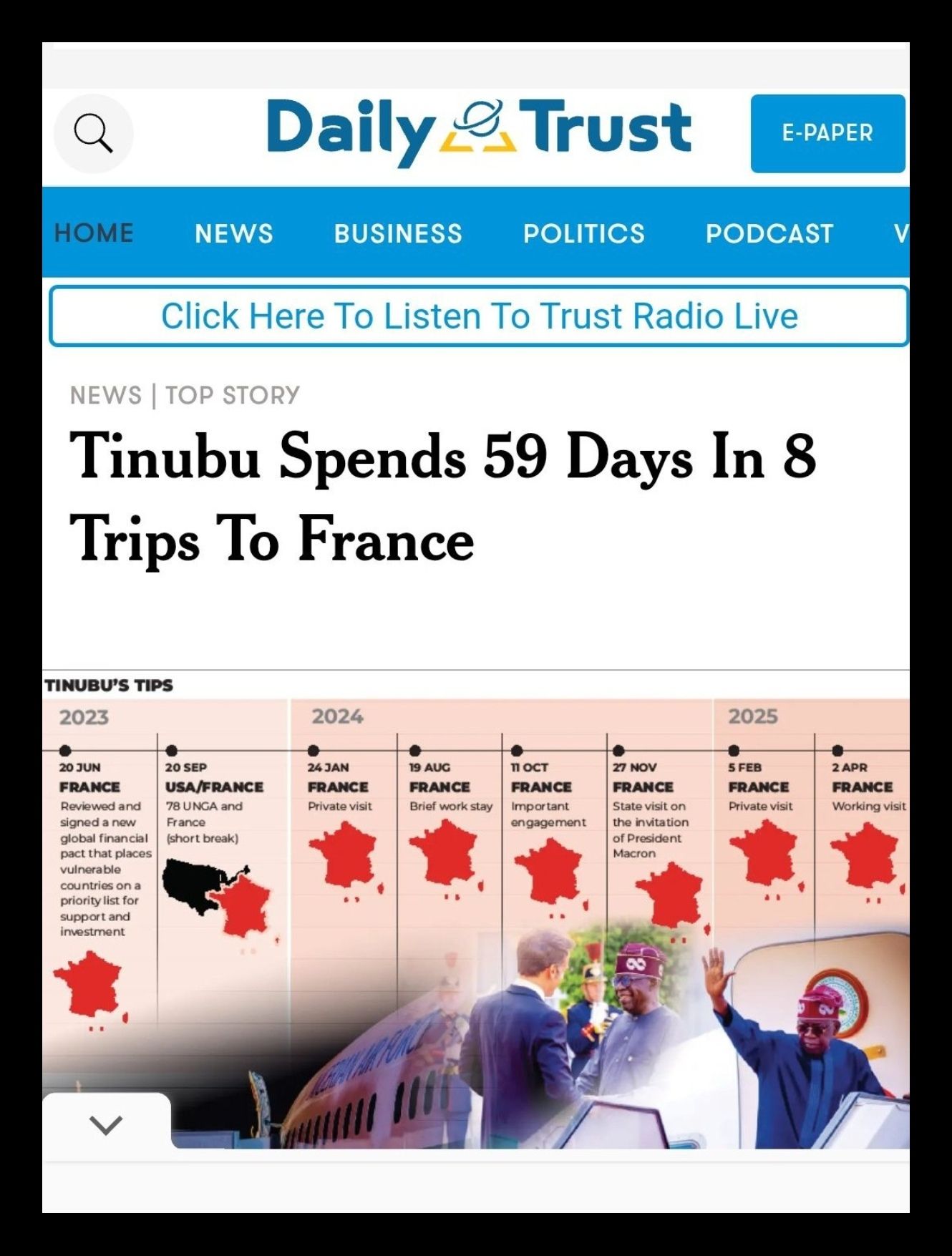

Nigeria’s agreement with France centres on automated compliance systems, artificial intelligence-driven audits, and data analytics applied to tax administration. French officials publicly described the arrangement as mutually beneficial, yet the structural asymmetry remains obvious. France lost direct colonial control over West Africa, but retained institutional expertise in fiscal extraction, population monitoring, and administrative enforcement. Tax data reveals income distribution, consumption patterns, business structures, geographic movement, and political exposure. Economic historians such as Walter Rodney described taxation systems as the backbone of colonial administration, allowing metropoles to extract value without constant military enforcement. Modern digital tax systems perform the same function at far greater scale and precision.

Legal scholars focusing on data sovereignty argue that aggregated data retains strategic sensitivity even when individual records are anonymised. Professor Teresa Scassa of the University of Ottawa has shown that aggregated datasets allow accurate reconstruction of behavioural and economic patterns, particularly when combined with external datasets. Once transferred, recipient states gain long-term leverage over fiscal policy design, enforcement thresholds, and revenue forecasting. Nigerian officials claimed raw taxpayer data would not leave the country, yet cross-border analytics require data visibility, modelling access, and algorithmic training inputs. Control shifts gradually through dependence on foreign technical infrastructure and expertise.

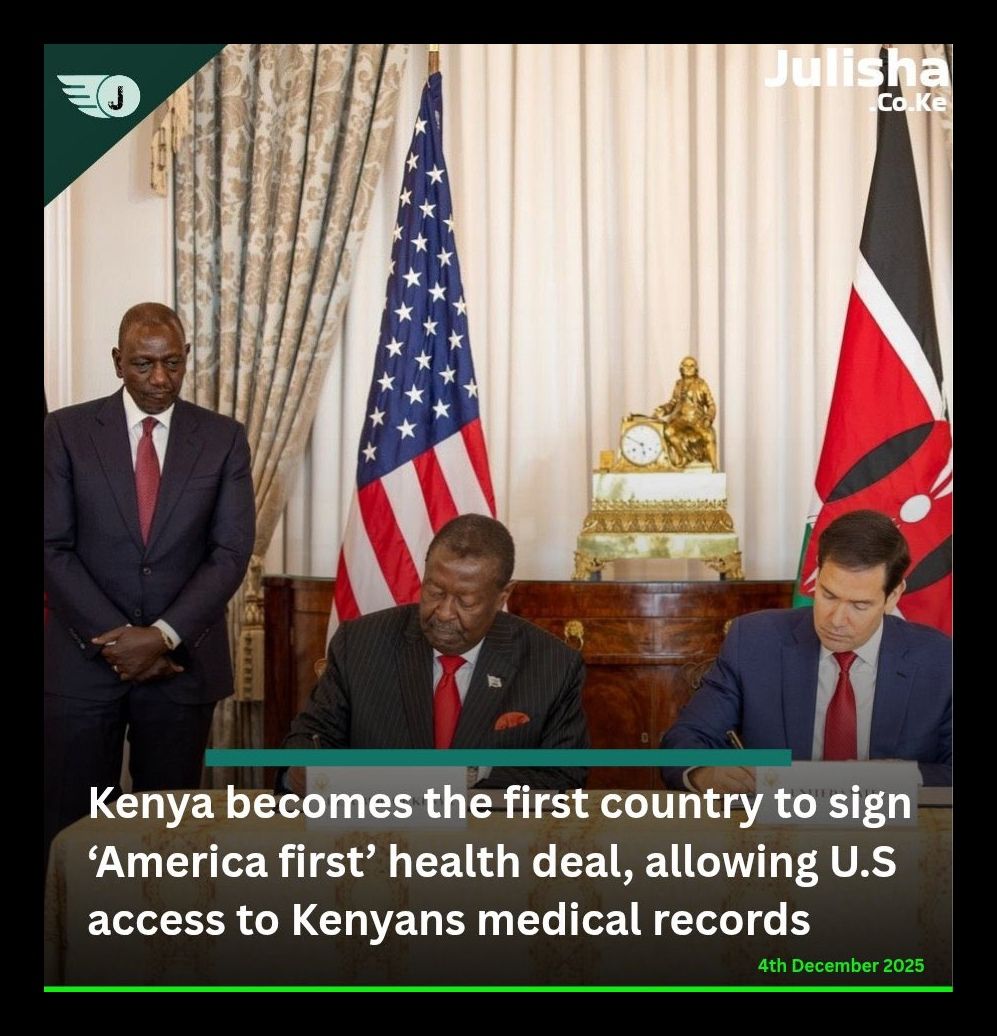

Kenya and Rwanda’s healthcare data agreements with United States agencies follow a similar logic, though framed through public health cooperation and biomedical innovation. Health data constitutes a nation’s most comprehensive intelligence resource, covering genetics, disease prevalence, medication response, mental health trends, and demographic vulnerability. Dr. Vandana Shiva and other critics of bio-colonialism have long warned that genomic and health data extraction enables pharmaceutical monopolies, patent capture, and long-term dependency. African populations become research substrates while value creation occurs abroad, protected by intellectual property regimes enforced through international trade law.

These agreements proceeded without informed consent from citizens or transparent legislative debate. Constitutional scholars such as Kenya’s Patrick Lumumba have argued that consent cannot be implied through executive authority when fundamental rights over bodily autonomy and privacy are involved. Data protection laws across these states remain underdeveloped, particularly regarding biometric, genomic, financial, and geolocation information. Nigerian legal advocates warned legislators that tax and GPS data lacked explicit classification as sensitive national security assets. Parliamentary inaction allowed executive agencies to proceed under international pressure.

India offers a cautionary precedent rather than a model. Rajiv Malhotra’s extensive work on digital colonisation documents how Indian data assets were surrendered to foreign platforms under the guise of innovation and growth. Indian labour built artificial intelligence systems whose ownership, governance, and profit streams remained external. Domestic startups were absorbed by multinational corporations, while the state relied on foreign infrastructure for digital public goods. Indian policymakers retained flags and constitutions while losing epistemic control over information flows, cultural narratives, and behavioural conditioning. African states now face the same trajectory at a faster pace and with weaker institutional resistance.

The consequences extend beyond economics into political control. Scholars Nick Couldry and Ulises Mejias describe data colonialism as appropriation of human life through quantification, producing asymmetrical power relations resembling historical empire structures. Behavioural data allows external actors to influence elections, social movements, consumption habits, and public opinion without visible coercion. Military intervention becomes unnecessary when information systems shape perception and compliance. The Benin coup and wider Sahel instability revealed how external powers maintain influence through selected elites rather than popular legitimacy. Leaders function as administrative intermediaries rather than representatives of their populations.

United States government documents increasingly frame health, technology, and data cooperation as components of national security strategy. Former intelligence officials have openly described data as the new strategic resource, replacing oil and minerals. African healthcare datasets feed artificial intelligence systems used for military logistics, population modelling, and predictive governance. Professor Shoshana Zuboff’s analysis of surveillance capitalism demonstrates how data extraction concentrates power while hollowing democratic accountability. African states lacking bargaining power exchange permanent data access for temporary funding, technical assistance, or political support.

United Nations and World Economic Forum initiatives under Agenda 2030 promote digital identity systems, interoperable health records, and cross-border data frameworks. Official language emphasises inclusion and efficiency, yet governance structures consistently place decision-making authority outside national jurisdictions. Political economist Quinn Slobodian documents how global governance regimes bypass democratic processes in favour of technocratic rule. African governments adopt these frameworks without public mandates, often under debt pressure or diplomatic leverage. Citizens inherit digital systems designed elsewhere, governed elsewhere, and monetised elsewhere.

Recolonisation today operates through standards, platforms, and dependencies rather than direct occupation. Control over data infrastructure determines future industrial capacity, defence readiness, and political autonomy. States unable to withdraw from foreign systems lose the ability to act independently during crises. China and Russia recognised this threat earlier and imposed strict data localisation, platform controls, and sovereign cloud infrastructure. African states remain divided, exposed, and reliant on external assurances that history repeatedly disproves.

Independent African economists such as Samir Amin warned that peripheral integration into global systems rarely produces development without internal capacity building. Data extraction mirrors raw material export patterns, leaving value-added processes abroad. Artificial intelligence trained on African data will generate products sold back to African governments at monopoly prices. Dependency deepens while sovereignty erodes incrementally, rarely triggering immediate public outrage because consequences unfold quietly over years.

Political accountability weakens when leaders negotiate away strategic assets without electoral consequences. Executive authority expands while citizen oversight contracts. Digital systems introduced without consent condition populations into compliance through service dependency. Refusal becomes impractical when healthcare access, taxation, banking, and identification require participation. Epistemic control replaces overt repression, producing what social theorists describe as managed consent.

Five hundred years of slavery and domination by the West, the Africans have learnt little, even from the current global events. The risks of these decisions become clearer when placed against recent evidence of how the same data firms operate in active conflict zones. An Associated Press investigation confirmed that artificial intelligence systems developed by Microsoft and OpenAI were integrated into Israeli military targeting operations in Gaza and Lebanon, marking one of the first documented uses of commercial AI in live warfare. Those systems relied on large-scale data ingestion, predictive modelling, and pattern analysis drawn from civilian information streams. The outcome demonstrated how population data, once absorbed into security architectures, can be repurposed for surveillance, targeting, and lethal decision-making without public oversight. African governments transferring tax, health, and biometric data to foreign partners are placing similarly comprehensive population profiles into ecosystems already proven capable of military application. Control over such data determines not only economic planning or healthcare delivery, but also how populations can be mapped, categorised, and acted upon during political crises, civil unrest, or external intervention. The Gaza precedent shows that assurances of benign use hold little weight once data enters integrated intelligence systems governed beyond the reach of affected citizens. Just think about how quickly Israel and its backers introduced AI to genocide. The world was meant to adopt this technology very cautiously because as it poses an existential threat. These African leaders, however much they being bribed, they are insane. They actually believe that by redacting names and identifiers, AI is incapable of putting this data back together and linking it to the correct identities. That’s probably one of the lies they were sold.

African states face a narrowing window to assert data sovereignty through constitutional protection, legislative oversight, and domestic technical capacity. Failure to act ensures a future defined by algorithmic governance designed elsewhere. Historical empires extracted labour and resources until resistance emerged. Digital empires extract behaviour, identity, and decision-making itself, leaving little space for reversal once systems mature. African governments should suspend all cross-border data-sharing agreements pending public disclosure, parliamentary review, and constitutional scrutiny. National data protection laws must classify financial, biometric, genomic, and geolocation data as strategic assets with strict localisation requirements. Domestic capacity building should replace reliance on foreign technical systems through regional cooperation and independent infrastructure development. Citizens require enforceable rights over data use, withdrawal, and redress. Sovereignty must extend beyond borders into digital and epistemic domains if independence is to retain meaning.