BBC News, Delhi

Reuters

ReutersIndian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was one of the first world leaders to visit Washington weeks after US President Donald Trump started his second term.

He called Modi his “great friend” as the two countries set an ambitious target of doubling their trade to $500bn by 2030.

But less than six months later, the relationship appears to have hit rock bottom.

Trump has now imposed a total of 50% tariffs on goods imported from India, and his earlier threat of levying an extra 10% for the country’s membership in the Brics grouping, which includes China, Russia and South Africa as founding members, still stands.

He initially imposed a 25% tariff, but announced an additional 25% on Wednesday as a penalty for Delhi’s purchase of Russian oil – a move the Indian government called “unfair, unjustified and unreasonable”.

And just last week, Trump called India’s economy “dead”.

This is a stunning reversal in a relationship that has gone from strength to strength over the past two decades, thanks to efforts by successive governments in both countries, bipartisan support and convergence on global issues.

In the past few weeks, there were positive signals from Washington and Delhi about an imminent trade deal. Now that looks increasingly difficult, if not impossible.

So what went wrong?

A series of missteps, grandstanding, geopolitics and domestic political pressure seem to have broken down the negotiations.

Delhi has been restrained in its response so far to Trump’s tirades, hoping that diplomacy might eventually help secure a trade deal. But in Trump’s White House, there are no guarantees.

Trump has commented on many issues that Delhi considers red lines. The biggest among them is Trump repeatedly putting India and its rival Pakistan on an equal footing.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesThe US president hosted Pakistani army chief Asim Munir at the White House just weeks after a bitter conflict between the two South Asian rivals.

He then signed a trade deal with Pakistan, offering the country a preferential tariff rate of 19%, along with a deal to explore the country’s oil reserves. He went as far as saying that some day, Pakistan might sell oil to India.

Another constant irritant for Delhi is Trump’s repeated assertion that the US brokered a ceasefire between India and Pakistan.

India sees its dispute with Pakistan over Kashmir as its internal affair and has always rejected third-party mediation on the issue. Most world leaders have been sensitive to Delhi’s position, including Trump in his first stint as president.

But that’s no longer the case. The US president has doubled down on his claim even after Modi told India’s parliament that “no country had mediated in the ceasefire”.

Modi didn’t name Trump or the US but domestic political pressure is mounting on him not to “bow down” to the White House.

“The fact that this is happening against the backdrop of heavy and high-level US engagement with Islamabad immediately after an India-Pakistan conflict is even more galling for Delhi and the wider Indian public. This all sharpens concerns harboured by some in India that the US can’t truly be trusted as a partner,” says Washington-based South Asia analyst Michael Kugelman.

He adds that some of the anger in Delhi might “be Cold War-era baggage coming to the fore”, but “this time around it’s intensified by real-time developments as well”.

Modi’s government thrives on nationalist issues, so its supporters would likely expect a firm response to the US.

It’s a Catch-22 situation – Delhi still wants to clinch a deal but also doesn’t want to come across as buckling under Trump’s pressure.

And it appears that Delhi is gradually releasing the restraint. In its response to Washington’s anger over India’s purchase of Russian oil, Delhi vowed to take “all necessary measures” to safeguard its “national interests and economic security”.

But the question is why Trump, who loved India’s hospitality and called it a great country earlier, has gone on a tirade against a trusted ally.

Some analysts see his insults as a pressure tactic to secure a deal that he thinks works for the US.

“Trump is a real estate magnate and a tough negotiator. His style may not be diplomatic, but he seeks the outcomes diplomats would. So, I think what he’s doing is part of a negotiating strategy,” says Jitendra Nath Misra, a former Indian ambassador and now a professor at OP Jindal Global University.

A source in the Indian government said that Delhi gave many concessions to Washington, including no tariffs on industrial goods, and a phased reduction of tariffs on cars and alcohol. It also signed a deal to let Elon Musk’s Starlink start operations in India.

But Washington wanted access to India’s agriculture and dairy sectors to reduce the $45bn trade deficit it runs with Delhi.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut these sectors are a red line for Modi or, for that matter, any Indian prime minister. Agriculture and related sectors account for more than 45% of employment in India and successive governments have fiercely protected farmers.

Mr Kugelman believes giving in to Washington’s demands isn’t an option for India.

“India first needs to assuage public anger and make clear it won’t give in to the pressure. This is critical for domestic political reasons,” he says.

He also believes that Trump’s insistence that India stop importing oil from Moscow has more to do with his growing frustration over Russian President Vladimir Putin.

“We’re seeing Trump continuing to ratchet up his pressure tactics, trying to cut Russia off from its most important oil buyers by penalising them for doing business with Moscow,” he says.

But Delhi can’t afford to stop importing oil from Russia overnight.

India is already the world’s third biggest consumer of crude and may surpass China in the top position by 2030 as its energy demand is likely to increase with a fast-growing middle class, according to International Energy Agency (IEA).

Russia now accounts for more than 30% of India’s total oil imports, a significant jump from less than 1% in 2021-22.

Many in the West see this as India indirectly funding Moscow’s war but Delhi denies this, arguing that buying Russian oil at a discount ensures energy security for millions of its citizens.

India also sees Russia as its “all-weather” ally. Moscow has traditionally come to Delhi’s rescue during past crises and still enjoys support among the wider Indian public.

Moscow is also Delhi’s biggest arms supplier, though its share in India’s defence import portfolio dropped to 36% between 2020-25 from 55% between 2016 and 2020, according to Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

This was largely due to Delhi boosting domestic manufacturing and buying more from the US, France and Israel.

But Russia’s role in India’s defence strategy can’t be overstated. This is something the West understood and didn’t challenge – until Trump decided to break from established norms.

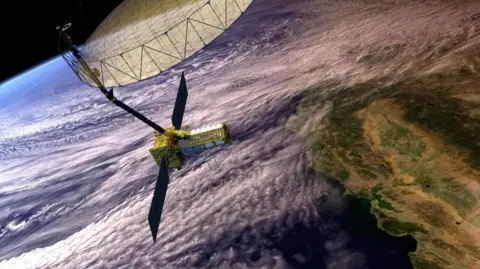

NASA

NASASo far, India was able to successfully walk the diplomatic tightrope with the West overlooking its strong ties to Russia.

The US has long viewed India as a bulwark against China’s dominance in the Indo-Pacific region, which ensured bipartisan support for Delhi in Washington.

And Moscow (though sometimes reluctantly) didn’t react harshly to its ally forging close ties with Washington and other western countries.

But now Trump has challenged this position. How Delhi reacts will decide the future of the India-US relationship.

India has been measured in its response so far but is not holding back completely. In its statement, it said that the US had encouraged it to keep buying oil from Russia for global energy market stability.

It also said that targeting it was unjustified as the EU continues to buy energy, fertiliser, mining and chemical products from Russia.

While things seem bad, some analysts say that all is not lost. India and the US have close links in many sectors, which can’t be uprooted overnight.

The two countries cooperate closely in the space technology, IT, education and defence sectors.

Many large domestic IT firms have invested heavily in the US, and most big Silicon Valley firms have operations in India.

“I think the fundamentals of the relationship are not weak. It’s a paradox that the day Trump announced 25% tariffs and unspecified penalties, India and the US collaborated in a strategic area when an Indian rocket sent a jointly-developed satellite into space,” says Mr Misra.

It will be interesting to see how India reacts to Trump’s sharp rhetoric.

“Trump is unapologetically transactional and commercial in his approach to foreign policy. He has no compunction about deploying these potentially alienating harsh tactics against a close US partner like India,” says Mr Kugelman.

But he adds that there’s a lot of trust baked into the partnership, given the work that has gone into it over the past two decades.

“So what’s lost can potentially be regained. But because of the extent of the current malaise, it could take a long time.”

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.