Let’s talk about money, specifically the use of bribery as a weapon in war and geopolitics. Like any weapon, it has technical characteristics and operational effects. In the ancient world bribery was practiced openly in the form of tribute paid by subject states to dominant powers. Masters were bribed to “protect” their subjects. In the modern era, bribery is legally discouraged and notionally repudiated by all, yet it persists as a significant factor in the conduct of armed conflicts and geopolitical struggles. Although international bribery of military and political figures is clandestine, a great deal can be deduced from occasional disclosures of these practices. When making a case for a crime, lawyers frequently assemble evidence for means, motive, and opportunity, so I will follow that model in this discussion. Although I will focus on U.S. government practices in this discussion, other major countries act in a similar, if more limited, manner.

The Means of Government Bribery

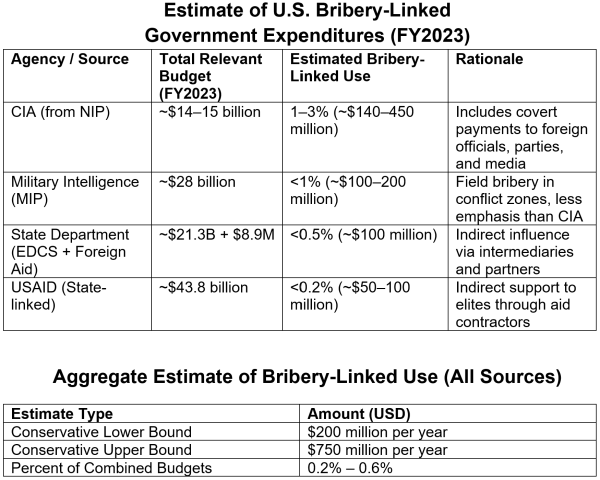

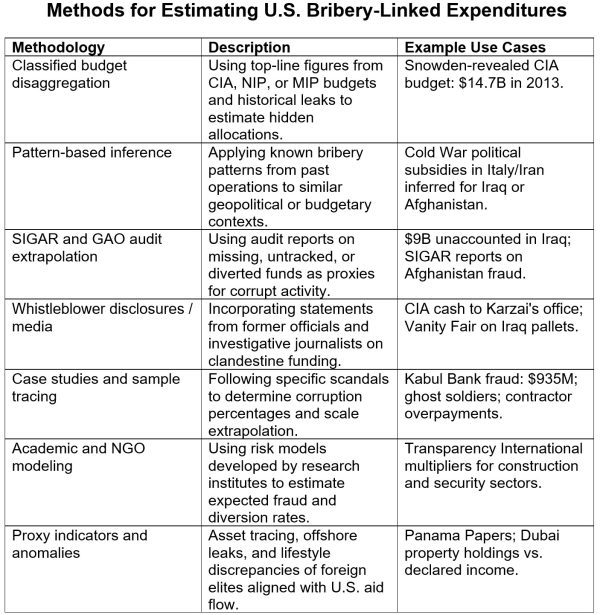

The U.S. has considerable resources available for bribery. The black budgets of the U.S. intelligence agencies and discretionary funds of the State Department amount to many billions of dollars. Even a small fraction of this amount can fund a massive amount of international bribery. Analysts have developed a number of tools for estimating the scope of this clandestine activity.

The Motives for Government Bribery

The benefits of bribing foreign officials include securing markets for U.S. corporations, establishing military bases, obtaining intelligence information, and preventing other nations from receiving more favorable treatment than the U.S. If there is a potential for armed conflict, it is usually cheaper for the U.S. to bribe than to fight, but if armed force is applied, bribery increases the chances of victory, as it did in the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Another cost-effective form of military bribery is the funding of proxies, such as the overthrow of the Assad regime in Syria by operation Timber Sycamore. There are many desperate young men willing to take up arms for pay, and the loyalties of their leaders are often for sale. Of course, once a proxy war reaches a sufficiently large scale, covert financing is no longer feasible, and the U.S. provides direct aid to “allies.”

The Opportunities for Government Bribery

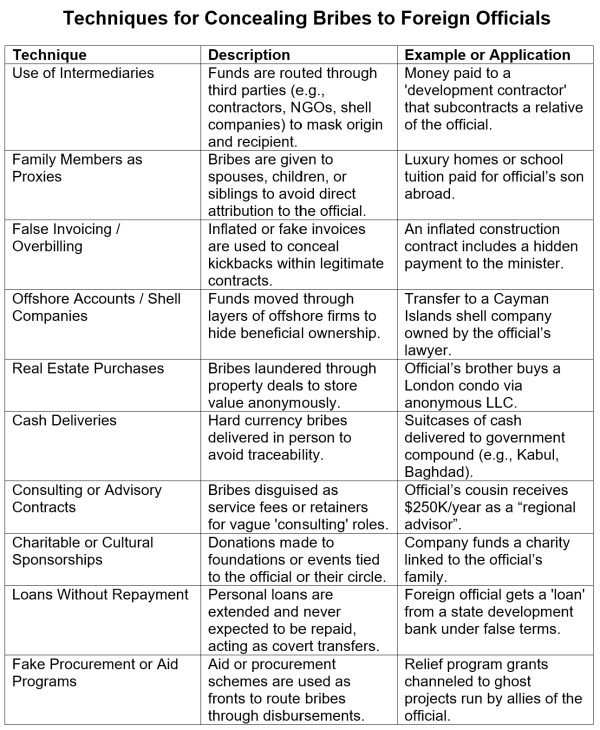

The opportunities for bribery of foreign officials are provided through the elaborate and effective financial techniques by which large bribes can be delivered secretly. The U.S. government relies on the same methods that wealthy individuals and criminals use to conceal the sources and destinations of large cash transactions. These methods involve cutouts, shell companies, multiple offshore bank transfers, and many other techniques that make investigation and discovery of the bribes nearly impossible

.

.

Although Congressional oversight of U.S. intelligence agencies notionally requires disclosure of bribery transactions, the information provided to Congress generally does not include identification of the parties participating in the bribery process. Thus the U.S. government maintains secret ties to many individuals and institutions whose purpose is to facilitate clandestine bribery. Once one grasps the considerable scale of U.S. bribery of foreign officials, many puzzling events in international relations start to make sense.

Clandestine bribery functions not as a rogue tactic but as a systemically embedded instrument of U.S. foreign policy, enabled by legal ambiguity, institutional compartmentalization, and perceived strategic necessity. Though individual payments may be small in scale, their cumulative effect is substantial: reshaping political outcomes, sustaining alliances, and projecting influence beneath the threshold of official diplomacy. Accordingly, bribery should be suspected in cases where foreign officials exhibit unusual decision-making, such as abrupt reversals of longstanding positions, unexplained shifts in policy alignment, or the initiation of unexpected diplomatic or military initiatives that lack clear domestic justification.

Curious Cases Suggesting Bribery

- The Philippines’ recent antagonistic posture toward China, its largest trading partner. This stance includes: – Granting expanded basing rights to the U.S. – Publicly challenging Chinese maritime claims – Reorienting military procurement toward Western suppliers. Such a pivot, particularly in the face of substantial economic costs, raises the possibility that covert inducements were involved.

- Eastern European Alignment with U.S. Defense Policy: The accelerated shift by certain Eastern European states to host advanced U.S. military installations—despite domestic political divisions and economic dependence on regional neighbors—suggests the possibility of inducements to override internal resistance.

- Overnight Policy Reversals in West Africa: Sudden terminations of Chinese infrastructure contracts in favor of U.S.-backed development alternatives, particularly in politically unstable or economically distressed nations, raise questions about the presence of behind-the-scenes financial incentives.

- Support for Controversial UN Resolutions: Instances where small or economically vulnerable countries reverse longstanding non-alignment stances to support controversial U.S. positions in international forums (e.g., votes on sanctions or recognition issues) may reflect the influence of off-the-record payments or promised aid.

- Surprise Recognition of Diplomatic Allies: Nations that unexpectedly sever ties with traditional economic partners to recognize U.S.-backed governments or territorial claims (e.g., Taiwan over China) without public consultation may be acting under covert inducement.

These examples are not presented as proven cases of bribery, but as pattern-consistent anomalies in foreign policy behavior that, when viewed through the lens of established clandestine funding practices, merit close scrutiny.

Conclusion

There is abundant evidence that the U.S. government has institutionalized practices of bribery of foreign military and political officials. Thus bribery, explicit or indirect, is a plausible explanation for unexpected decisions of foreign leaders favorable to the U.S. but contrary to the interests of their nations. The U.S. Congress should act to restrain this activity because of its potential to undermine Constitutional war powers and trigger undeclared wars. Intelligence agency disclosures to Congress should fully describe the means by which bribery is effected. Utilizing bribery, a fundamentally corrupt practice, in “defense” of U.S. national security undermines the international reputation of the United States and betrays the trust of citizens in their government. The money weapon is a poor choice for inclusion in an arsenal of democracy.