BBC Balkans correspondent

DAMIR SENCAR/AFP via Getty Images

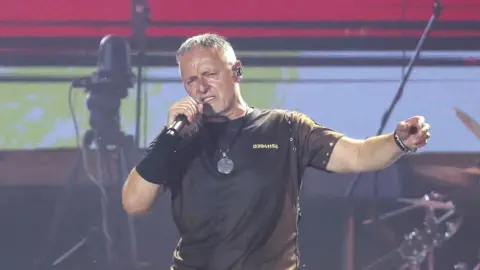

DAMIR SENCAR/AFP via Getty ImagesA “neo-fascist Croatian Woodstock” or patriotic, anti-establishment fun?

Last month’s mega-gig by the ultra-nationalist singer Thompson – the stage name of Marko Perkovic – has dramatically exposed the polarised divisions deep within Croatian society.

It shone a spotlight on wildly differing interpretations of both the country’s struggle for independence in the 1990s, and the history of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), a World War Two-era Nazi puppet state.

Nobody would argue that the concert was anything other than huge. Thompson’s management claimed that more than half a million tickets for the show at Zagreb Hippodrome were sold. The actual attendance was considerably lower – but still in the hundreds of thousands.

That enormous crowd enthusiastically joined in when Thompson launched into his opening number, Čavoglave Battalion. To his cry of “Za dom” (“for homeland”), the audience roared back “Spremni!” (“ready!”). MPs from the governing HDZ party were among those chanting along.

Reuters

ReutersThis chant has outraged opposition parties and organisations working for human rights and ethnic and regional reconciliation. They point out that “Za dom, spremni” originated with the anti-Semitic, Nazi-allied Ustasha organization during World War Two – and that Croatia’s Constitutional Court has ruled that the phrase “is an Ustasha salute of the Independent State of Croatia [which is] not in accordance with the Constitution of the Republic of Croatia”.

“This has opened Pandora’s box,” says Tena Banjeglav of Documenta – Centre for Dealing with the Past, an organisation which focuses on reconciliation by taking a factual approach to both World War Two and the more recent war of independence.

“You’ve now got politicians in parliament screaming ‘Za dom, spremni’. On the streets, kids are singing not only that song, but other songs Thompson used to sing which glorify mass crimes in World War Two,” she says.

“The government is creating an atmosphere when this is a positive thing. It is creating a wave of nationalism which could explode into physical violence.”

The government has in fact downplayed the chanting at the concert. Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic described it as “part of Thompson’s repertoire” and posed for a photo with the singer the day before the Zagreb gig.

Conservative commentator Matija Štahan believes that Thompson’s time serving as a soldier during the war of independence gives him the right to use “Za dom, spremni” in his work.

“It is an authentic outcry for freedom against aggression,” he says.

“Many journalists in the West say it’s the Croatian version of ‘Heil Hitler’ – but it would be best to describe it as the Croatian version of [the Ukrainian national salute] ‘Slava Ukraini’.

“Both rose to prominence in the context of World War Two – which was a war for many small nations who wanted their own independent states,” Mr Štahan says.

“Symbols change their meaning – and just like ‘Slava Ukraini’, ‘Za dom, spremni’ also means something different. Today, it’s an anti-establishment nationalist slogan. It’s against the Croatian politically-correct post-communist political elite. Young people want to shout it as something that’s subversive.”

This interpretation cuts no ice with the Youth Initiative for Human Rights (YIHR), a regional organisation which works for reconciliation among the younger generations in the Western Balkans.

“It is clearly a fascist slogan,” says YIHR’s director in Croatia, Mario Mažić.

“As an EU member state, Croatia should be an example for the rest of the region, but it has not dealt with the past. It identifies with the losing side in World War Two, doesn’t recognise it waged an unjust war in Bosnia and refuses to acknowledge systematic crimes against Serbs.”

Thompson staged another huge show at the start of August in Krajina, the stronghold of Croatian Serbs during the war of independence. That performance was part of the celebrations for the 30th anniversary of Operation Storm – the military battle which ended Croatia’s war of independence from Yugoslavia in the 1990s, but which also displaced hundreds of thousands of Serbs.

In recent years, the government had started to include commemorations for Serb victims. But reconciliation now appears to have a lower priority than promoting nationalist sentiment, with a military parade in Zagreb the showpiece of this year’s events.

“All these things became more visible since the UK left the European Union – because when it comes to anti-fascist values, it can’t be only up to Germany to protect them,” says historian Tvrtko Jakovina.

Mr Jakovina believes this is convenient for a government which seems to have no answers to the numerous challenges facing contemporary Croatia.

“In the summer of 2025, we don’t talk about the problems with our tourism, climate change, non-existent industry, higher education – or the demographic catastrophe that’s looming,” he says.

“Instead, we’re talking about the military parade and two Thompson concerts.”