Yves here. Even though my rewritten headline to a VoxEU piece (originally Risks in the new international trade landscape) may seem surprising, you’ll see that its even its opening paragraph depicts risks that have long been underway as if they were relatively new developments. The reason for showcasing this article despite that is that it contains useful analysis such as import concentration of particular high technology products, that gives a much more granular feel for where Chinese imports are particularly dominant or otherwise hard to replace.

Nevertheless, this post is another demonstration of the danger of fealty to neoliberal dogma, here, that liberalized trade will solve all problems. I recall in high school, while doing debate research, I came across an article in a serious policy journal about how the US (IIRC the military) depended on certain nations in Africa for key minerals (again IIRC, the centerpiece of the article was rhodium) where supplies were not at all reliable and the geopolitics of the particular exporters made them less so. In the unipolar moment, if not earlier, concern about strategic needs and resulting vulnerabilities seems to have gone out the window.

By Florencia Airaudo, Economist Board Of Governors Of The Federal Reserve System; Francois de Soyres, Chief of Advanced Foreign Economies Federal Reserve Board Of Governors; Ece Fisgin, Research Assistant Federal Reserve Board Of Governors; Alexandre Gaillard, Postdoctoral Fellow, Julis-Rabinowitz Center for Public Policy & Finance Princeton University; Ana Santacreu, Economic Policy Advisor Federal Reserve Bank Of St Louis; Keith Richards, Research Assistant Federal Reserve Board Of Governors; and Henry Young, PhD candidate University Of Michigan. Originally published at VoxEU

Global trade is entering a new era shaped by geopolitical alignment and China’s evolving role. China has become a direct competitor in high-tech sectors while dominating critical input markets, creating dual risks for advanced economies in the form of supply dependence and industrial displacement. These risks increasingly reinforce one another, challenging traditional trade logic. This column document these shifts using new data on trade flows, technological overlap, and input concentration – highlighting the strategic vulnerabilities facing advanced economies, particularly in Europe, as trade becomes more politicised.

As advanced nations rethink supply chain security and industrial resilience, international trade is entering a new phase – driven less by efficiency and more by strategic logic. Three concurrent forces are transforming trade: selective geopolitical fragmentation, China’s rapid technological rise, and its dominance over rare earths and other critical inputs (Alfaro et al. 2025).

A growing literature shows trade patterns increasingly reflect foreign policy alignment (Gopinath et al. 2024, Goldberg and Ruta 2025, Airaudo et al. 2025). In this column, we build on these insights to examine the broad contours of trade fragmentation and the risks China’s evolving role pose for the outlook for advanced economies. In particular, we highlight how industrial competition and input dependence reinforce strategic vulnerabilities for advanced economies.

While we do not advocate for any specific trade policy, our goal is to provide a positive analysis of recent structural shifts in global trade. In principle, a world with minimal trade frictions – where efficiency and comparative advantage guide trade flows – would be welfare-enhancing, but recent developments suggest a growing role for strategic considerations.

Selective Geopolitical Fragmentation

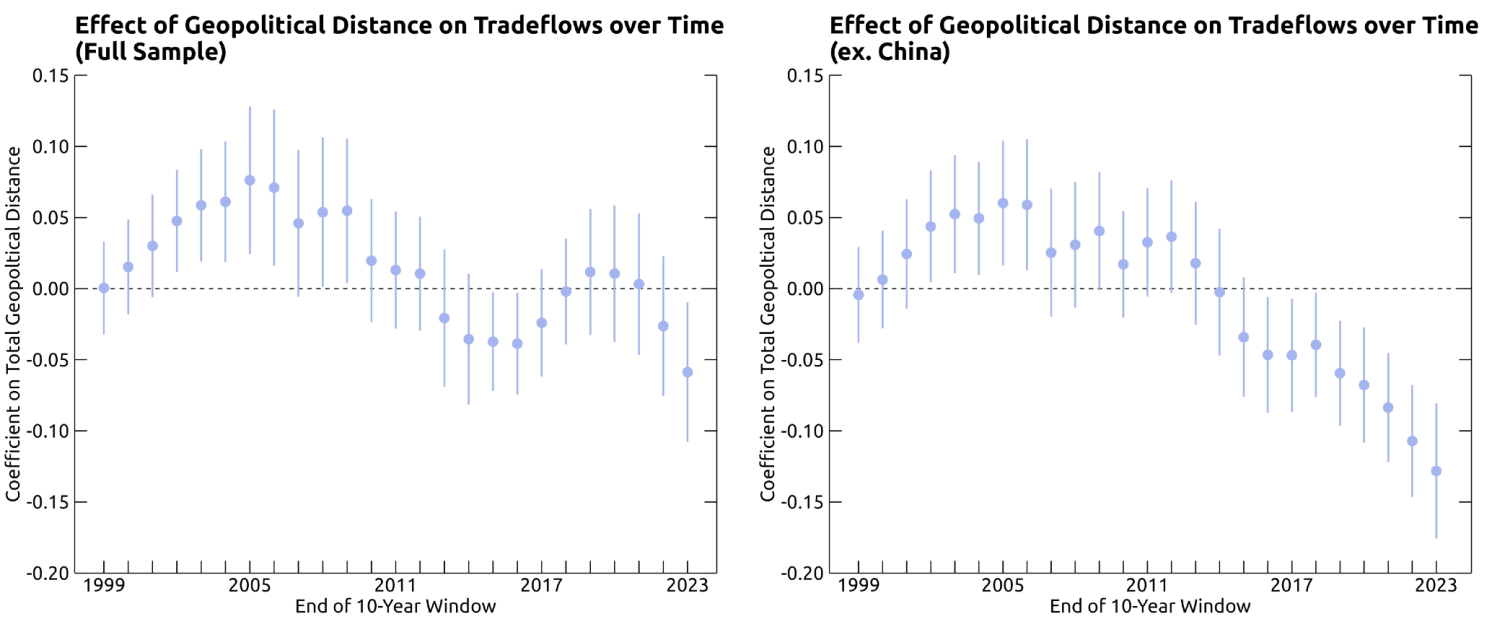

Geopolitical alignment is increasingly shaping trade flows, but the pattern is selective – and China plays a unique role. To quantify geopolitical distance, we use the Ideal Point Distance (IPD), based on how closely countries’ UN voting patterns align (Bailey et al. 2017, Airaudo et al. 2025). 1 Using geopolitical distance based on all votes, we estimate its impact on bilateral trade using a standard gravity framework, using a ten-year rolling window and controlling for conventional trade determinants.

The left panel of Figure 1 shows that geopolitical distance has begun to weigh on trade, though the effect is moderate. Excluding China (right panel), the correlation becomes much stronger – reflecting China’s distinctive behaviour of expanding exports broadly while compressing imports, which dampens the overall link. This suggests that fragmentation is real but uneven, with China masking underlying shifts. It is also sector-specific: in Europe, fragmentation is concentrated in low-tech goods; in the US, high-tech sectors are more affected.

Figure 1 Association between geopolitical distance and trade flows

>

China’s Rising Competition

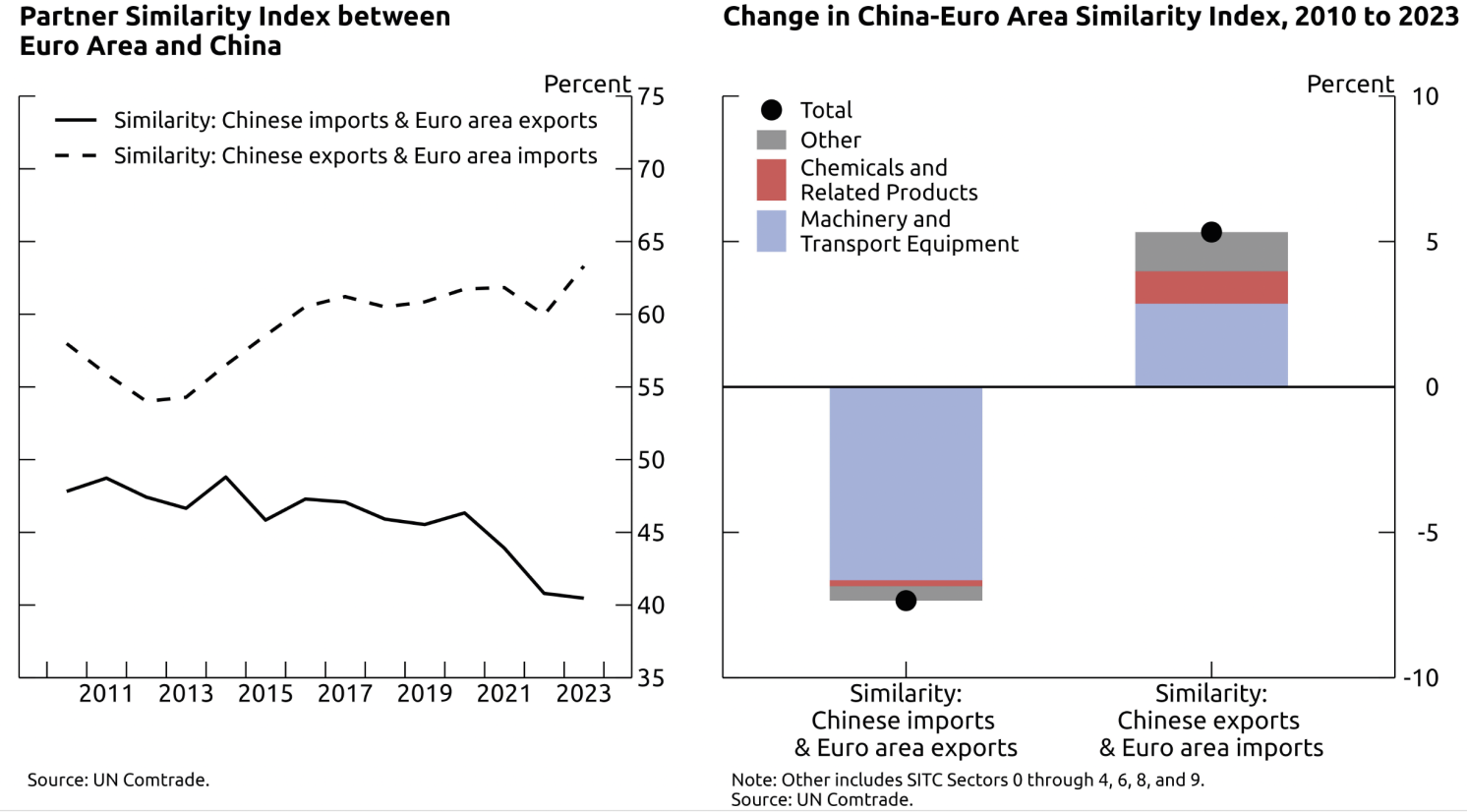

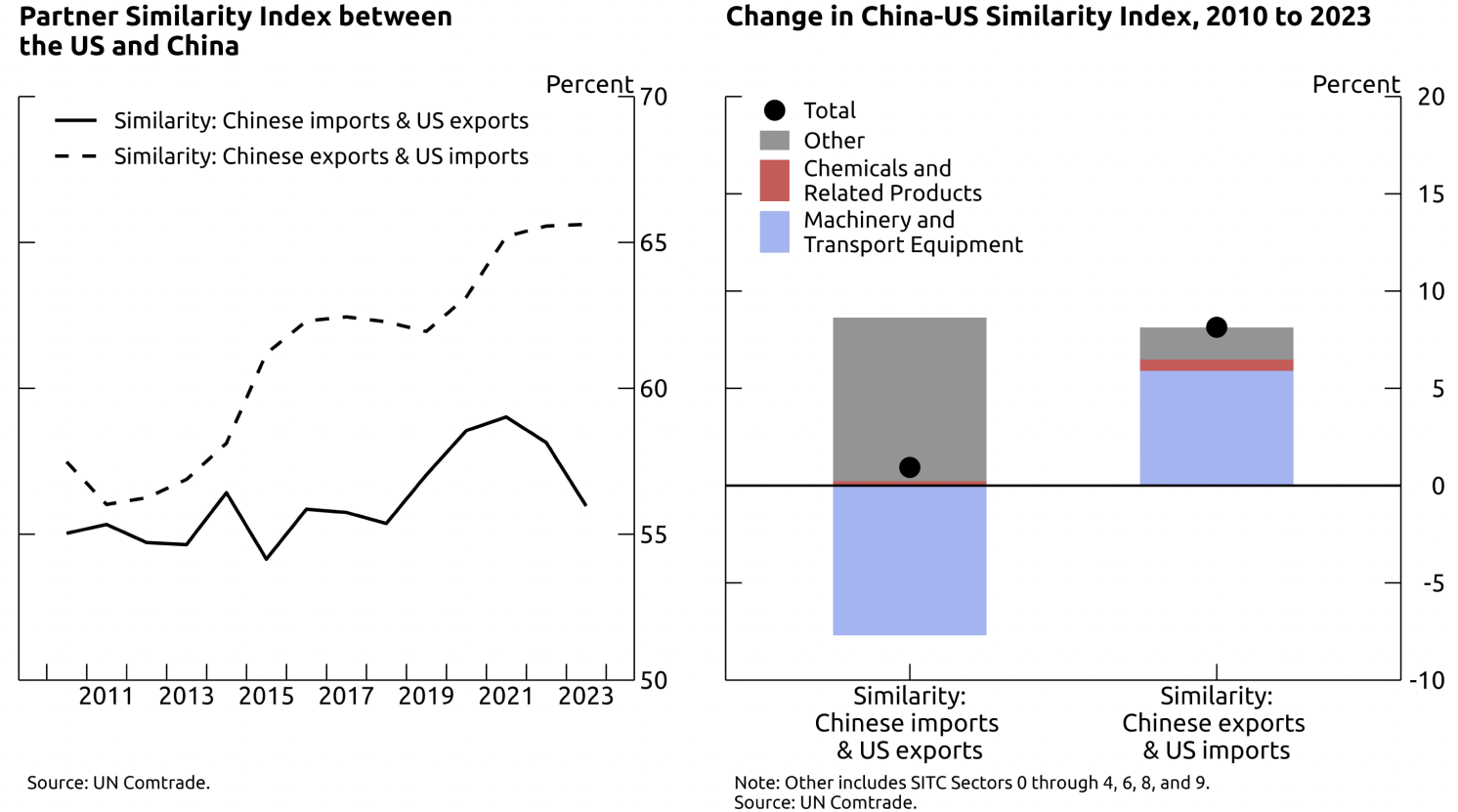

China is becoming a more competitive and asymmetric trade partner for advanced economies. To assess how trade competition is evolving, we rely on the Partner Similarity Index (PSI), which quantifies how well an exporter’s sectoral specialisation match an importer’s sectoral demand (de Soyres et al. 2025a). Inspired by similarity indices introduced by Finger and Kreinin (1979), PSI values range from 0 to 100, with a higher number indicating stronger sectoral alignment.

Figures 2 and 3 show that the PSI between China’s exports and advanced economy imports has been rising steadily, especially in sectors such as machinery, electronics, and transport equipment. This indicates that, whereas China once specialised in cheap, low-tech goods, it is now increasingly supplying the types of goods that advanced economies demand – signalling a move up the value chain and a transition from production complementarity to direct rivalry.

At the same time, the PSI between advanced economy exports and China’s imports has declined. In particular, euro area exports are becoming less aligned with what China is buying, especially in the automotive sector. This divergence highlights China’s effort to become more self-reliant in strategic sectors, as also documented in de Soyres and Moore (2024).

Figure 2 Sectoral trade similarity between the euro area and China

Figure 3 Sectoral trade similarity between the US and China

These trends indicate not only intensified global competition but also growing asymmetry: while advanced economies are more exposed to China as a supplier, China is becoming less reliant on them as a market – exacerbating pre-existing trade imbalances between Western countries and China.

Innovation Catch-Up

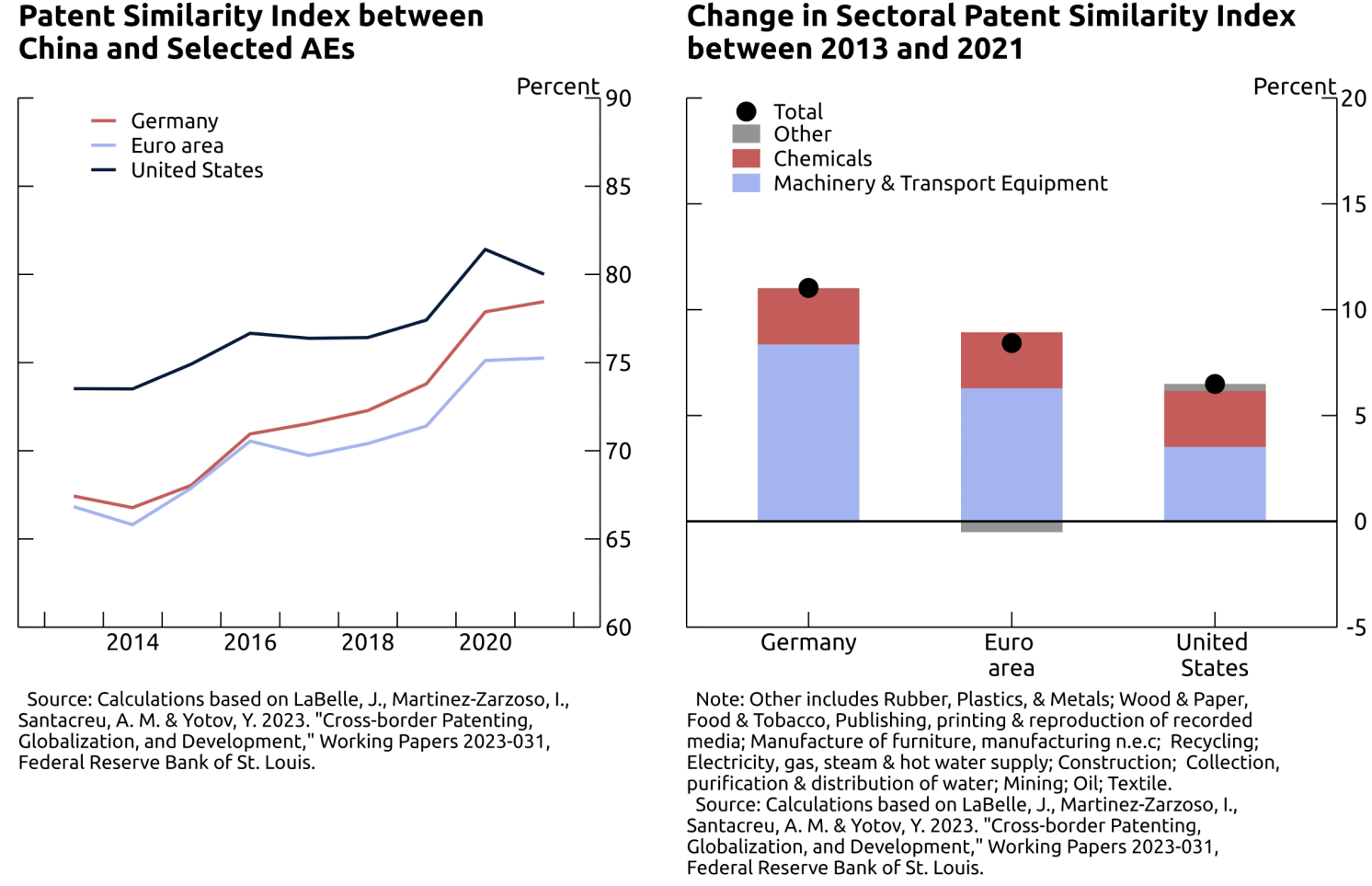

China is shifting from cost-based competition to innovation-led rivalry in strategic sectors. To understand whether this competitive shift is underpinned by technological capacity, we turn to patent data. When inventors or companies file patents abroad – what we call ‘patent exports’ – they are making strategic decisions that reveal their global ambitions. As discussed in LaBelle et al. (2023), companies typically pursue international patents to secure exclusive rights to sell their innovations in valuable foreign markets.

Figure 4 presents the Export Similarity Index (ESI) calculated using patent ‘exports’. The ESI provides a forward-looking measure of innovation overlap, tracking how similar the technological output of two economies is, sector by sector.

Figure 4 Patent Similarity Indices

Drawing on de Soyres et al. (2025b), we find that China’s patenting activity has surged in key sectors such as telecom, green energy, and electronics. The ESI between China and both the US and the euro area has increased markedly over the past decade, suggesting that China is not only producing what advanced economies demand, but also innovating in the same strategic sectors. Taken together, the PSI and patent-based ESI analyses show that China evolved from being a partner that sources advanced technology products from abroad, to being a mostly self-reliant rival in these sectors.

Strategic Inputs Dependence

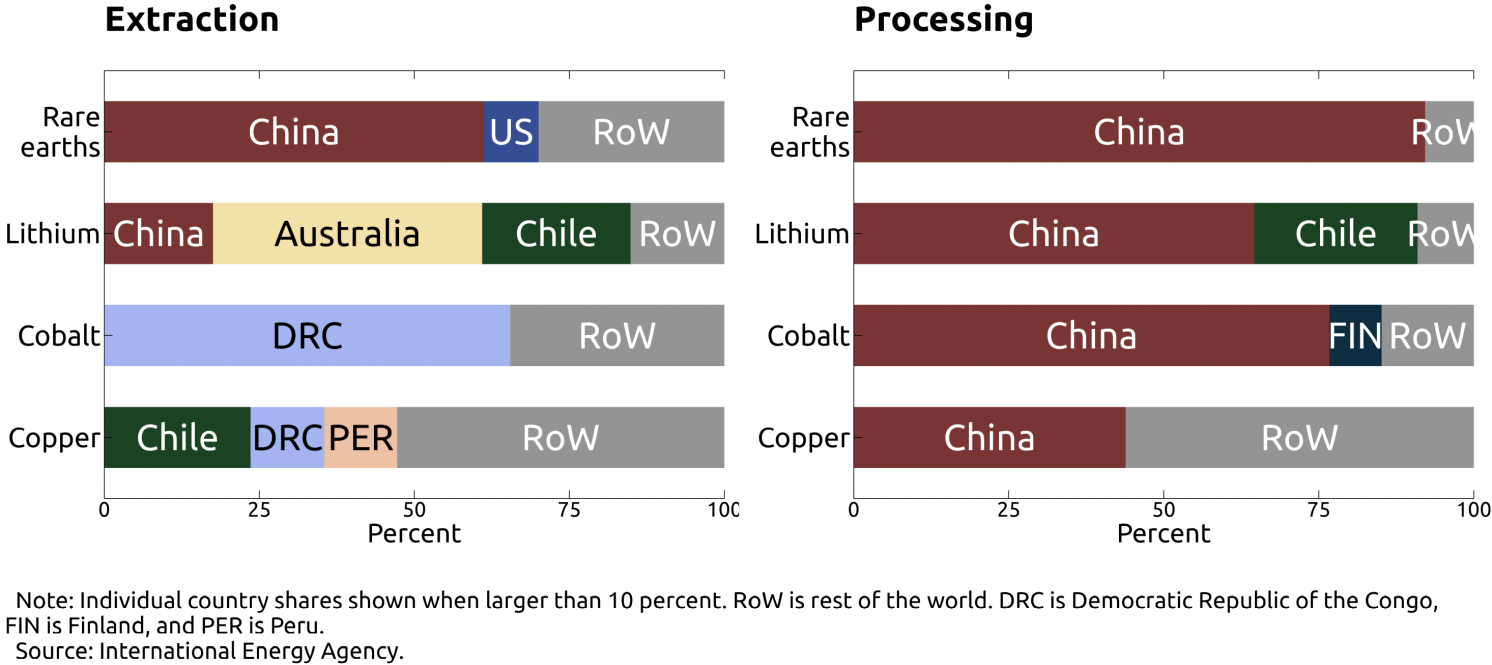

High import concentration in critical inputs creates structural vulnerabilities for advanced economies. Figure 5 illustrates China’s dominant role in the refining of critical minerals and rare earths. China alone accounts for over 90% of global rare earth processing and holds substantial shares of global capacity in refining other strategic materials. These inputs are essential to a wide range of industrial and defence applications and are difficult to substitute in the short term.

Figure 5 Global concentration of critical mineral supply chains, 2023

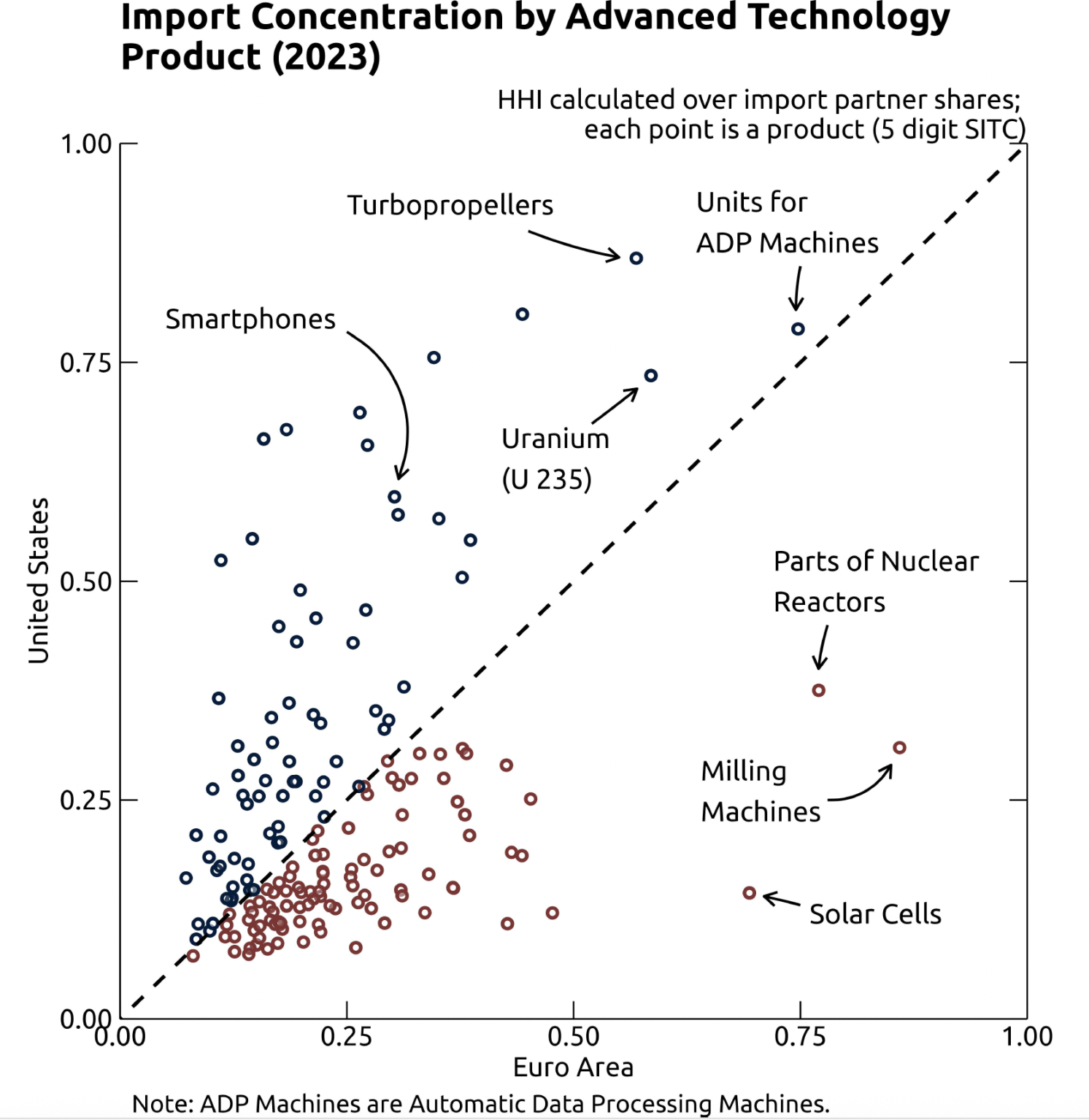

Figure 6, building on Mejean and Rousseaux (2024), shows that imports of advanced technology products are highly concentrated in both the euro area and the US, based on Herfindahl indices. While the specifics vary, both regions rely heavily on a few suppliers – many of them geopolitically distant – for critical inputs tied to the green and digital transitions. This concentration heightens the risk of supply disruptions from logistical shocks, trade disputes, or coercive policies.

Figure 6 Import concentration by advanced technology products, 2023

These vulnerabilities are not hypothetical. In 2010, China imposed export restrictions on rare earths amid a maritime dispute with Japan, cutting export quotas by roughly 40% and temporarily halting shipments to Japan. The move triggered sharp price increases and disrupted downstream industries across advanced economies, particularly in electronics, renewable energy, and defence. Recent policy developments suggest that similar restrictions remain a live possibility.

A Reinforcing Risk Structure

China’s rise in global trade poses two distinct but increasingly interconnected risks for advanced economies.

- First, China is a direct competitor in high-tech sectors – such as solar, electric vehicles, and telecom – where it challenges domestic producers through aggressive pricing and scale. This creates a substitution risk, as Chinese exports displace local production.

- Second, China dominates the supply of hard-to-replace inputs – like rare earths, graphite, and battery materials – creating a complementarity risk: advanced economies depend on Chinese inputs, making them vulnerable to export restrictions.

Crucially, these risks reinforce each other. By restricting critical inputs while offering ready-made substitutes, China can simultaneously disable foreign production and expand its own market share. This dual leverage magnifies strategic vulnerability, linking upstream control with downstream dominance. Addressing this challenge requires a coordinated response – combining innovation investment, supply chain resilience, and trusted international partnerships.

Focus on Europe

Fragmentation exposes monetary policy to structural risks. Inflationary pressures may rise, as reliance on geopolitically distant suppliers increases the likelihood of persistent supply shocks and greater inflation volatility. Strategic fragmentation can also raise market concentration, reducing competition and contributing to price stickiness. Moreover, uneven exposure across euro area member states complicates a unified monetary policy response.

Deeper internal integration could help the euro area respond more effectively to global fragmentation – not only by enhancing resilience, but also by boosting innovation and external competitiveness. Our new estimates suggest that internal trade barriers remain significant, driven by regulatory divergence, infrastructure gaps, and non-harmonised standards – despite years of progress, integration has largely stalled since the early 2010s. Reducing these frictions would expand the scale and efficiency of domestic production, helping European firms better compete in global markets. At the same time, a more integrated capital market would improve access to innovation financing and support broader risk-taking.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are our own, and do not represent the views of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis, nor any other person associated with the Federal Reserve System.

____________