Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution by Mark Copelovitch (University of Wisconsin – Madison) and Thomas Pepinsky (Cornell University).

Are cryptocurrencies viable as money? What is the economic function of “shitcoins” and “stablecoins”? And how can we understand the political economy of cryptocurrency and its implications for global finance, state sovereignty, and the international system? At a time when the U.S. government has floated the idea of a Strategic Bitcoin Reserve, and tech oligarchs question the viability of the sovereign state in the age of blockchains, there is a need for some clear and analytical thinking on the political economy implications of cryptocurrency.

We have a new working paper that addresses these questions, contributing some analytical clarity to current debates about blockchains, cryptocurrency, and the future of money that are currently dominated by those with a vested interest in crypto’s success. Our working title is “The Political Economy of Shitcoins.” Here is the abstract:

We study the political economy of cryptocurrency in a global economy comprised of states that issue fiat currency, considering the implications of crypto from the position of users, issuers, states, and the international system. The political implications of cryptocurrency follow from its ability to perform the three functions of money: unit of account, medium of exchange, and store of value. From these foundations, we draw on the established literature on the political economy of international monetary relations and international finance to derive predictions about the future of cryptocurrency in a world of sovereign states. We describe four possible futures for the international monetary system: a world without cryptocurrency, a world in which cryptocurrency exists alongside fiat currency, a world in which cryptocurrency has replaced traditional fiat currency, and a techno-futuristic world in which cryptocurrency spells the end of the Westphalian state system. We evaluate the political and economic stability of each of these four scenarios. We conclude that the most like scenario is one in which crypto survives alongside traditional fiat currency, but also highlight that the future of crypto is a battle over the future of sovereign authority itself.

Money is (domestic and international) politics

Recent technical work on crypto studies the possibility of regulation under decentralized finance. In a world where trusted intermediaries are no longer necessary due to the availability of smart contracts, can a decentralized and permissionless system provably guarantee that some transactions are forbidden? The answer is no: financial regulators cannot rely on a decentralized financial architecture if they also want to do things like implement exchange controls or ban money laundering. Similar constraints bind when we consider the political economy of cryptocurrencies. As crypto engages with political and economic systems, it is bound by existing findings from political economy.

Indeed, it is a central tenet of international political economy that money and finance are deeply intertwined with questions of domestic politics, state power, and sovereignty in the international system (Strange 1988, Kirshner 1997, Kirshner 2003). For centuries, states have been the units with sovereign authority to issue currency and the dominant actors shaping the global financial system (Helleiner 1994, Cohen 2004, Frieden 2020). Indeed, the current international monetary system is characterized by two main features: unprecedentedly large global capital flows and a global economy dominated by state-backed fiat reserve currencies – most notably the US dollar.

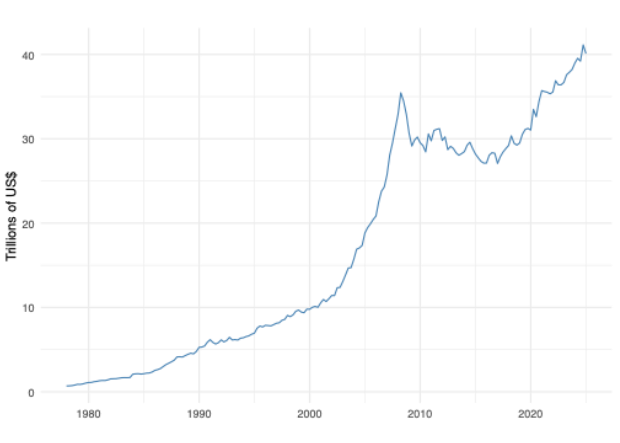

Total Cross-Border Banking Claims, 1977-2023

Source: Bank for International Settlements, series Q.S.C.A.TO1.A.5J.A.5A.A.5J.N (https://data.bis.org/topics/LBS/data).

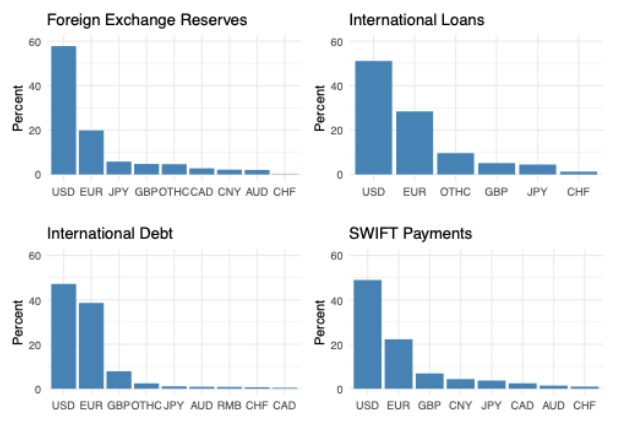

The Dollar’s “Full Spectrum” Dominance

Sources: Norrlöf 2023;Foreign Exchange Reserves from International Monetary Fund (https://data.imf.org/en/datasets/IMF.STA:COFER); International Loans from Bank for International Settlements (https://data.bis.org/topics/IDS/BIS,WS_DEBT_SEC2_PUB,1.0/Q.3P.3P.1.1.C.A.A.TO1.A.A.A.A.A.I) International Debt from Bank for International Settlements (https://data.bis.org/topics/LBS/tables-and-dashboards/BIS,LBS_A6_1,1.0?), SWIFT Payments calculated from Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (https://www.swift.com/swift-resource/252389/download)

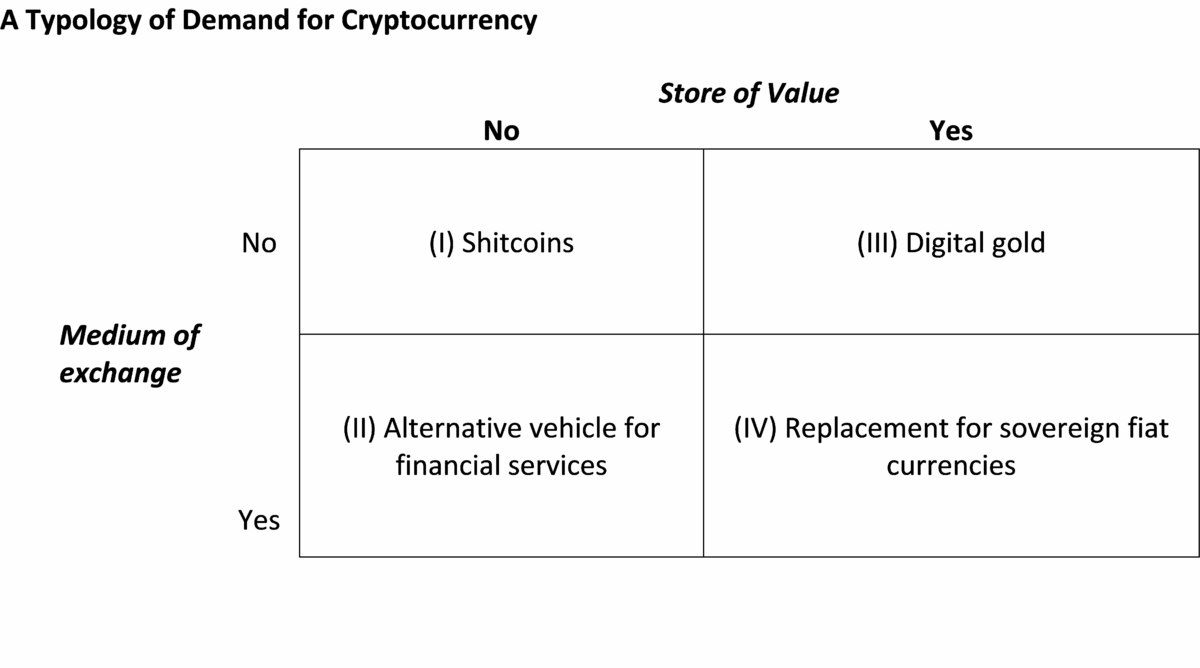

The political economy of crypto follows directly from the (in)ability of different crypto products to rival or replace state-backed fiat currencies in performing the three functions of money. From the perspective of users, demand for crypto is driven by both ideational and material factors. We can distinguish between actors who care about crypto itself as an asset with intrinsic value, as opposed to those who value crypto because of its instrumental value, i.e., its ability to enable them to achieve certain goals and perform certain desired activities in the global economy. Obviously, these overlap, with some actors valuing using or holding crypto or crypto-denominated assets for a combination of ideational factors and material reasons.

Put simply, different users demand different roles for crypto, depending on their interests in having it perform the medium of exchange and store of value functions of money in the global economy:

The political economy of crypto also depends on its supply—or more precisely, on how the supply of a crypto product is determined. If the supply of a crypto product is fixed in the short term and/or predictable in the future (e.g., Bitcoin), then it is like “digital gold.” On the other hand, if its supply is infinite (e.g., NFTs), then it’s worthless, like Bored Apes or Trump Digital Trading Cards. Indeed, there are strong parallels between certain types of crypto and gold as commodities with fixed or exogenous-determined supply. Adopting such varieties of crypto poses the same tradeoffs as adopting a fixed exchange rate in the well-known Mundell-Fleming trilemma (Mundell 1961, Aizenmann et. al. 2021). Yet the degree to which the trilemma “binds” varies substantially across crypto products. Major cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin and Ether, have fixed supply in the short run and the process of increasing supply is costly in both time and energy. These products are functionally equivalent to “digital gold”: their common feature is the costliness of creating more crypto, just like more gold cannot be created unless new supplies are discovered and mined.

The international monetary implications of adopting a currency whose supply is fixed are well-known from history. Both the Long Depression of 1873-96, and the Great Depression of the interwar era laid bare the long-term non-viability of an international monetary system built on a commodity whose supply cannot be increased in the short run to deal with major financial crises (Eichengreen 2008, Kindleberger 2005/1986). Thus, while Bitcoin and other similar crypto products may develop further as assets – and perhaps even carve out some modest role as alternatives to fiat reserve currencies – they simply will not reach the scale needed to serve as the world’s hegemonic international currency. Even a single dominant Bitcoin would face the energy, climate, and speed constraints on increasing supply to address the inevitable demand for liquidity that would emerge in future international financial crises. Brunnermeier and Niepelt (2019) demonstrate that cryptocurrencies cannot fulfill the same role as fiat currencies without the involvement of a politically committed central bank and/or a centralized record-keeping authority.

In contrast, “shitcoins” present the exact opposite problem. Since they are essentially costless to produce, they are useless as viable money in the global economy. Indeed, because the supply of shitcoins is unlimited, the value of any NFT is ultimately zero: as assets whose supply is infinite and effectively costless to increase, they are doomed to remain purely speculative commodities and vehicles for the pursuit of Ponzi schemes and criminal scams.

Crypto, states, and the future of the international monetary system

Put all this together, and you can think about the international political economy of cryptocurrency in a clear and analytical way. You can also see more clearly what techno-futurists who own blockchain protocols and tokens — the Balaji–Thiel class — are up to. Because states are at the heart of the global monetary order, replacing an international monetary system based on fiat currency with one based on crypto means challenging the role of the states in the modern economy. Lest you think this is exaggeration, the author of The Network State is a former Andreesen Horowitz partner who has a Substack where he recently posted that All Property Becomes Cryptography and has set up shop for his Network School in the failed megaproject of Forest City, Malaysia.

It is important to note that the mere existence of a non-state controlled medium of exchange is not a challenge to the current international monetary system. After all, this is the case with gold now and has been for the entire post-Bretton Woods era since President Nixon closed the “gold window” in 1971. Supplementing gold with forms of “digital gold” does not fundamentally alter the current international monetary “non-system” that has operated for decades, free of a specific metallic base standard norm or even norms about which exchange rate regime should prevail (Corden 1981/1983).

Instead, the distinctive novel feature of cryptocurrency is its portability. It is difficult to walk around with bags full of gold, but it is easy to do so with a wallet full of BTC or other crypto. Were crypto to become a large or majority share of global currency markets, it would limit the ability of states to implement financial regulation, capital controls, and monitor global capital flows in the world economy? While some states may choose to cede their ability to do these things, and some economic actors may favor such a future, the history of the international monetary order suggests that a monetary system that so constrains the policy options of national governments will not last long.

The main thing that stands in the way of this future world is the global system of states itself. State-backed fiat still rules the world, and the dollar stands atop the pyramid of fiat currencies as the overwhelmingly dominant medium of exchange and store of value in the global economy. But the threat of crypto is precisely why major central banks, including the Federal Reserve, are now taking central bank digital currencies (CDBCs) very seriously. One can readily imagine a future in which firms and individuals have bank accounts at the Federal Reserve denominated in digital dollars. In this future, the US government would merge blockchain technology with Census data to give every US citizen a federal account, through which digital dollars could be provided instantly without recourse to either the Postal Service or the commercial banking system. Rather than mailing stimulus checks to households, the Fed or a future presidential administration could simply transfer digital dollars directly to voters during economic crises.

This future raises its own set of questions about sovereignty and democratic legitimacy. For example, could the Federal Reserve Chairman or President do this even without Congressional approval? How do we prevent the government from abusing this new system by taxing or even closing individual accounts? But in this world, states would have reasserted control over monetary policy and money, and the crypto threat to supplant fiat currency and undermine state sovereignty would be eliminated.

Which of these futures – a world in which crypto rivals or replaces fiat currencies, or one in which states reassert control over global finance by co-opting crypto into the existing state-based international monetary system – will come to fruition remains uncertain. But it is quite clear, even now, that the future of crypto and the international monetary system are the frontier of the battle over the structure of world order in the second half of the 21st century.

This post written by Mark Copelovitch and Thomas Pepinsky.