For centuries, codfish in the Baltic Sea, which lies between Sweden and Eastern Europe, have been a regional dietary staple. Fishers once hauled in nets filled with cod more than three feet long, weighing as much as 85 pounds.

Cod are a keystone species, an apex predator that kept herring and sprat in check and provided nourishment for seals and other predators. But starting in the mid-1990s, cod numbers in the Eastern Baltic began to collapse, leading herring and sprat populations to increase and, in turn, overgraze zooplankton. Baltic cod fishing in the east has been banned since 2019 to allow the stocks to recover.

The numbers of cod aren’t the only thing that has shrunk — so has their average size. Eastern Baltic cod are roughly half as big as they were in 1996, and their median weight has dropped to roughly a fifth of what it had been in that year.

A recent study blames the change on heavy fishing pressure, which selectively removed larger fish, which are more profitable, from the population. That not only reduced cod numbers, it also changed the fish’s genome so they no longer grow as large or as quickly. Slower-growing fish — which stay smaller longer, and so avoid trawlers’ nets — have an advantage in the face of intense fishing pressure.

Biologists used to think evolution only played out over thousands of generations, but rapid human-induced evolution is now well-accepted.

“Selective overexploitation has altered the genome of the Eastern Baltic cod,” said Kwi Young Han, a postdoctoral researcher at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany, and lead author of the study. “We see this in the significant decline in average size, which we link to reduced growth rates.” These changes took place over 25 years.

Biologists used to think that humans did little to affect the course of evolution, that it was something that played out over thousands of generations. But rapid human-induced evolution is now well-accepted. Fish are a model for this phenomenon because they are so aggressively harvested that evolutionary changes show up rapidly, which has both management and economic implications.

Human-induced evolution has and is taking place in myriad species around the world. An oft-cited example is the peppered moth, which occurred in both white and dark forms in Britain and Ireland. Lighter-colored moths would rest on light-colored tree bark, protected from predators by their natural camouflage. But after the start of the Industrial Revolution, soot began blackening tree trunks — a condition that favored darker-colored moths. In the 1950s, biologists discovered that in industrial regions 80 percent of peppered moths had evolved to become dark colored because of its protective advantages.

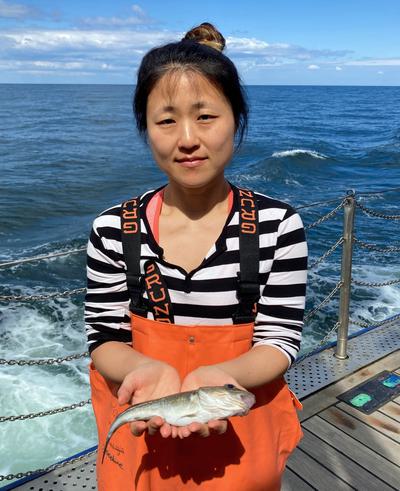

Left: A scientist holds a mature cod in 1987. Right: Biologist Kwi Young Han holding a mature cod today.

Photo by Jesper Bay of the Danish Institute for Fisheries and Marine Research, March 1987; Thorsten Reusch / GEOMAR

Trophy hunting has also been shown to induce rapid evolution. Bighorn rams in the Canadian Rockies can be shot legally only if their horns nearly complete a full circle, and many trophy hunters have sought out the larger horned animals. But larger horn sizes are indicative of genetic fitness, and hunter killing of larger-horned rams left more shorthorns to pass on their genes. Researchers saw a decrease in horn size over several decades, and studies have found sheep with larger horns are more genetically fit, which could impact the long-term health of the population.

During Mozambique’s 15-year civil war, which began in 1977, the armed forces killed 90 percent of the elephant population, targeting the animals to sell their tusks. As the population recovered, an unusually large percentage of females were born tuskless: the poaching had selected for animals with genes coded for tusklessness.

Studies of urban birds show that their human-influenced diets, traffic noise, fragmented habitat, and other factors are causing them to evolve in novel directions. Some city birds, for instance, have increased the general volume or frequency of their calls to be heard above noise, and a study in Arizona found that house finches had developed larger beaks, perhaps because backyard feeders provide harder seeds.

“If the largest animals are preferentially caught over the years, this gives the smaller individuals an evolutionary advantage,” says an ecologist.

While other studies have demonstrated that commercial fishing alters fish size and changes the trajectory of their evolution, the recent Baltic cod study is the best evidence yet for the concept of fisheries-induced evolution — the idea that human pressure on the world’s commercial fisheries has altered species’ genomes by removing the largest, fastest-growing fish, which in turn has altered the size of fish and subsequently their role in the marine ecosystem.

Until now, experts had lacked hard evidence of genetic changes, but new technology has enabled researchers to study changes at the genomic level. And the Eastern Baltic cod’s isolation from other cod species made them an ideal test case for linking the impact of fishing on cod genomes. “The paper is quite strong and mostly unassailable partly because of this unique situation,” said David Conover, an expert on fisheries-induced evolution at the University of Oregon, who wasn’t involved in the research.

To conduct her study, Kwi Young Han and her team in Germany examined the otoliths — a tiny ear bone that records a fish’s annual growth — of cod caught in the Eastern Baltic between 1996 and 2019. They combined that data with body-size metrics and DNA sequencing to determine whether there had been a genetic shift in the population. Scientists identified genetic variants that are associated with body growth and examined whether they became more or less frequent over that period. Their data showed that the fastest-growing fish have nearly disappeared, while slower-growing cod, which reach maturity at a smaller size, have proliferated.

Dark and light peppered moths. As industrial soot blackened trees, most of the moths evolved to become darker to be better camouflaged.

Bill Coster IN / Alamy

“If the largest animals are preferentially caught over the years, this gives the smaller, faster-maturing individuals an evolutionary advantage,” said Thorsten Reusch, head of GEOMAR’s marine ecology research department and one of the paper’s authors. “What we are observing is human-triggered evolution — fishing-induced selection. This is scientifically exciting, but ecologically — of course — highly dramatic.”

Genetic changes and overfishing are not the only problems that Eastern Baltic cod face. Diseases, parasites, and declining salinity, due to increasing amounts of freshwater inflow, are all taking a toll. This year the Baltic saw the warmest water temperatures since records have been kept. The warmer climate is also increasing the extent of hypoxic conditions — dead zones — in the sea, which are deadly to cod.

The genetic changes in fish stocks in the Baltic have taken place in commercial fisheries globally. Some researchers partly blame fishery managers who ignore science and set unsustainably high quotas to satisfy industry demand for larger catches.

The loss of big fish has another effect. “It compromises the population because larger fish lay way more eggs than smaller fish do,” said Conover. “It’s an exponential relationship.”

Research has shown that big, old, fat, fertile, female fish — known as BOFFFFs — are key to resilient populations of many of the world’s fish species: They not only lay more eggs, but their larvae grow faster and are much less likely to starve. BOFFFs also have a longer spawning season and lay their eggs in many different sites, thus increasing the chances their offspring will survive.

Unfortunately, in places like the Eastern Baltic, the genes for large fish have already disappeared, which complicates their recovery.

It is unknown what the changes in genetic diversity, driven by fishing pressure, might mean. “Diversity allows [fish] to hedge their bets in the face of variable or unfavorable environmental conditions” and adapt in the future, said Julie Charbonneau, a fisheries researcher in British Columbia. By losing that diversity, she said, “you are potentially losing some resilience and the ability to recover down the line.”

Smaller fish that have fewer offspring “can reduce both the productivity of a stock and its value on the market,” said Hanna Schenk, an evolutionary biologist who studied the decline of Baltic cod while at Leipzig University.

Ecological changes have been seen in parts of the Baltic, said Han. Because cod are apex predators, “top-down control is way weaker, and this has a cascading effect on the lower-level food web,” she said. “The predators are gone and there are larger populations and sizes of smaller fish, so there is less zooplankton that smaller fish feed on and more phytoplankton. This can lead to eutrophication [over-enrichment with nutrients] and other problems.”

In the new paper the researchers say a different kind of planning is needed to improve the sustainability of fisheries — one that adopts a century-long planning horizon and may include the introduction of size-selective harvesting, tracking changes in population genetics, and creating more marine protected areas where fishing is banned.

Bighorn rams in Jasper National Park in Canada. Trophy hunting has led to a decline in average horn size.

franzfoto.com

“More selective fishing could reverse evolutionary decline in the long term,” said Martin Quaas, head of the biodiversity economics group at the German Center for Integrative Biodiversity Research. Protecting fish, though, likely won’t do much to increase their size in the short term because, while fishing is a strong driver of evolution, natural selection happens more slowly. In fact, cod fishing has been banned in the Eastern Baltic for six years and yet “there’s no sign of a rebound in body size,” said Han.

Some research shows, however, that if genomes that favor faster growth and larger size still exist in the population, protection from fishing can help cod regain their size and age structure.

From an economic standpoint, “fishing should have largely avoided undesired evolutionary changes” by allowing more larger fish to survive, Quaas said. “Now that these changes have taken place, they are costly to reverse in the short run, but in the long run this would pay off in economic terms.”

Unfortunately, in places like the Eastern Baltic, the genes for large fish have already disappeared, which complicates their recovery. That’s why the Stockholm-based nonprofit Baltic Waters launched, in 2022, a project called ReCod, which annually releases off the coast of Sweden between 1 million and 1.5 million yolk sac larvae with genetic and phenotypic variations.

There is already much criticism of fisheries management for ignoring science in favor of profit. Now that advances in technology are helping scientists understand how human behavior affects the evolution of fish, managing fisheries will be even more complex — and important.

“This whole concept was denied,” said Han. “It’s been denied for a long time because it’s hard to prove [that fisheries-induced] evolution is happening. This paper is bringing that discussion back into play and saying, ‘It is happening.’ I hope it’s a turning point and people move toward more sustainable management.”