& I do not have one. I do have scattered observations on how it might work out for the tech industry. How it is affecting the overall business cycle—that is another equally complicated topic that will have to wait for another day. What we do see is tech giants pouring ungodly massive sumds of hundreds of billions into data centers where profits are elusive, out of a fear that disruption rewards outsiders, not incumbents. Programmer copilots, ad targeting, boilerplate-construction, and AI-slop creation tools as we see them today hardly justify the scale. But what new things will emerge? Colossal investment, uncertain payoffs, except for the makers of digital picks-&-shovels & the grifter VCs moving over from crypto to AI…

It is time to pause and consider just how gonzo the AI-economy truly is. The sharp Tabby Kinder at the FT:

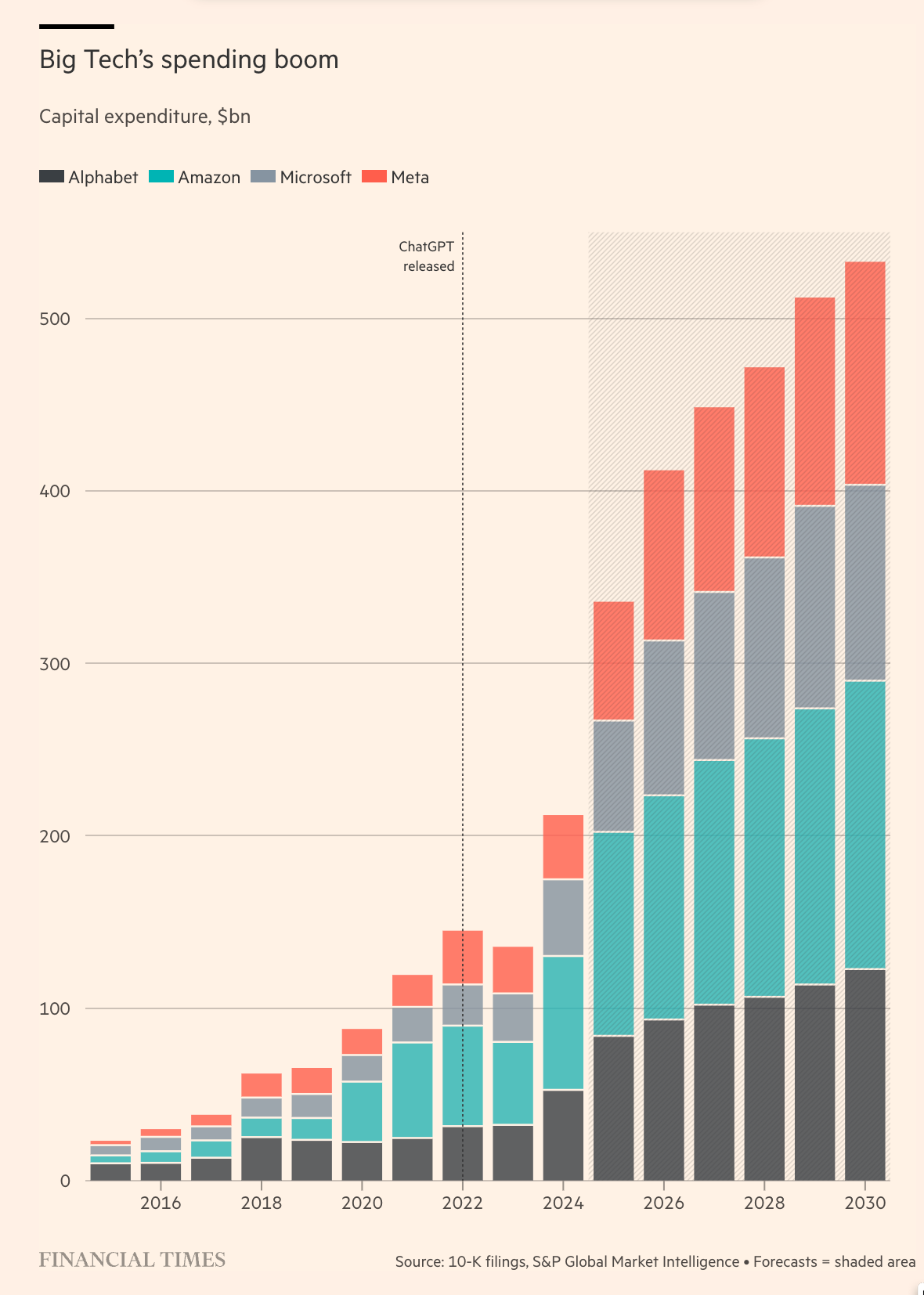

Tabby Kinder: “Absolutely Immense”: the companies on the hook for the $3tn AI building boom <https://www.ft.com/content/efe1e350-62c6-4aa0-a833-f6da01265473>: ‘Spending… to build the data centres… to power the AI era… “is absolutely immense,” said Rob Horn… at… Blackstone…. Google, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta will spend more than $400bn on data centres in 2026 — on top of more than $350bn this year…. The US has about 20 gigawatts of operational data centre capacity. Before the end of the year, another 10GW… projected to break ground globally… Historically… the “hyperscalers” — Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure and Google Cloud… [investments for] cloud services businesses w[ere] self-funded. But the scale of computing power needed…. Iinternal cash flows largely covered… $200bn last year, costs are projected to double this year and increase furthre next… [yet] hyperscalers’ generative AI revenues were just $45bn last year….

“People are making forecasts on the assumption that all enterprises will start to use AI technology and pay… enough… to justify…these… facilities,” said a banker.… “That we’re all going to be using AI all the time for everything. That…incomprehensible world… [is what] you need… [to keep] this all ends up losing money…”… “We view cloud services data centre build-outs as fairly robust. We are less confident long-term in the AI training-only locations,” said one executive at a large develope… “in 10 years you [may] just have a shed with obsolete GPUs and cooling infrastructure…”… Still, the hyperscalers can afford the risk…. “Microsoft and Amazon…are just gobbling up everything because popular opinion is that it’s a winner-takes-all market…”

And I have the natural observations, which I want to write down here all in one place:

I think the AI boom is the main prop of the current expansion. Remove data‑center spending, the GPU scramble, armies of prompt engineers, and the venture surge for anything labeled “AI,” and the economy is perilously close to stall speed. Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Meta alone plan $400 billion in data centers in 2026, dwarfing past tech cycles and rivaling the interstate highway system or Apollo. Hiring in tech‑adjacent sectors—chips, cloud, consulting—has been robust, cushioning the economy against higher rates and post‑plague normalization.

It is anticipation of AI‑driven productivity—and the capital expenditures to chase it—that keeps the ship sailing forward. But will, in the end, these software architectures be useful enough for their broad adoption? Will enough of the value generated be diverted from consumer to producer surplus? Or will it be a minus for the world but a plus for tech corporate shareholders and investors via malevolent attention-focused brain hacking/ We do not know. Thus whether this ends in a bust or a true transformation, and how big a bust, is for now hidden behind an impenetrable veil of time and ignorance. For now, we see that without this employment and production would almost surely be in a Bad Place, and that there is not yet a marked-out path to mammoth profitability consonant with the mammoth investment scale.

I have thought for a considerable length of time that the investments to graft natural‑language interfaces onto the “sticky” services monopolized by Google, Amazon, FaceBook, and Microsoft are less about profit than survival, or at least about CEO status in the sense that ranking in their pecking order depends on success, and that it is not clear it is better in the eyes of their peers to efficiently and profitably manage decline than to flame out spectacularly. Gelsinger is better regarded today for losing massive amounts of money for Intel than his more finance-regarding predecessors who ran that gold mine to exhaustion.

Plu: disruption is rarely polite. The iPhone eviscerated Nokia and BlackBerry; Google search left Yahoo and AltaVista as footnotes. Today, generative AI and chatbots threaten to obsolete those interfaces and the cash flows behind them (DeLong, Substack). Hence the billions for data centers and LLM training: defensive insurance against a nimble upstart with a more “natural” interface. Returns on such spending are often elusive; direct payback may never arrive, but the chance that standing still would be catastrophic is too high. This build‑out resembles an old-fashioned arms race: not to win decisively, but to avoid defeat. And so of all the tech platform oligopolists, only Apple is essentially sitting this one out.

Google’s search monopoly, once an unassailable gold mine, now perhaps faces an existential threat. First, its search is crippled because it swims in an ocean of SEO‑optimized content—a potential Achilles’ heel. Chatbot rivals, free of SEO baggage and possessing a natural-language interface, deliver plausible conversational answers that are not SEO-warped as they bypass click-and-scroll. An even if Google manages to match answer quality, the economics shift. An ad model built on result‑page engagement can evaporate when a single exchange answers the query with no click‑through. Victlry here may well be Pyrrhic. The old money flow may not exist in the new régime, no matter how strong the constructed defensive moat.

I see the executives of the tech platform oligopolies—Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and FaceBook—as powerfully haunted by the stories they tell themselves of the past of their industry, by which they rose to deserved prominence, wealth, and status by outmaneuvering those who could not see how fast and in what directions tech was changing. They see tech history as littered with giants felled by what they classify under complacency. With fear of AI‑driven disruption defining the moment. flush with cash and memories, they build, buy, and preempt in an orgy of defensive paranoia, not confidence.

Profits, if they come, are unlikely to flow substantially to the tech giants. They are too busy fortifying their moats.

Gains will go instead to the makers of “picks and shovels” and to nimble outsiders who carve new niches beyond the oligopolists’ reach.

The obvious parallel, of course, is in the stories we tell of the California Gold Rush: miners rarely struck it rich, but sellers of Levi’s, shovels, and whiskey did. In today’s AI boom, the equivalents are ASML, TSMC, NVIDIA, and similar firms. Their products fuel the computational arms race, yet they avoid the zero-sum struggle for platform dominance. Perhaps also with an edge are those who can profit from scale as providers of computational capacity, Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and perhaps another rising hyperscaler or two. I do not see where there mammoth future profitability will come from. But I am given pause by the fact that I do not understand why AWS today is so massively profitable. There are clearly important things that I do not understand here.

Meanwhile, truly outsized returns may await those who invent genuinely new and improved services—applications of AI that solve problems or create value in domains the platform giants cannot or will not fully control. Transformation often comes from the periphery, not the center; the platform oligopolists’ efforts to preëmpt an crush competition within their core markets may leave the field open for innovation elsewhere The challenge ispredicting where those green shoots will emerge.

The next wave of service providers will be those who exploit the scale and flexibility of modern AI—massive-data, multi-attention-layer models that now wield what once seemed infinite computing power. The truly gold mine-scale money-making breakthroughs, if there are to be any, still lie ahead, not yet visible.

Thus there is still a big question: What, concretely, are the “new-and-improved” services that justify the AI boom? For now, the list is rather thin. Programmer copilots like GitHub Copilot boost output for the already-productive if not yet for experts, offering quick solutions. FaceBook claims its multi-attention-layer models deliver ad-targeting gains, refining content to hack user attention. Productivity tools for managing the funnel of information overload seems to work. And so does automating the production of documents of boilerplate and ritual. Plus, unfortunately, picking-up-nickels by attention-hacking via the creation of massive amounts of AI-slop.

Thus we are living through an extraordinary, gonzo moment in the industrial-organization of technology. Trillions are being mobilized to build AI infrastructure on a scale comparable only to the interstate highway system, Apollo, or perhaps the Cold War arms race. And yet, the payoffs remain almost entirely notional as we point to copilots, advertising tweaks, and productivity funnels that are incremental in terms of money flows even though they do promise to produce massive amounts of user surplus.

The payoffs now and visible in the future do not yet justify $400 billion a year in concrete, silicon, and cooling towers by the cold calculus of financial-economic profit and loss.

If transformative applications arrive, today’s spending will look prescient—the necessary down payment on a new technological régime. If they do not, these “hyperscaler” investments may be remembered as the most expensive defensive panic in business history, an orgy of capital immolation spurred by fear of becoming the next Nokia or Yahoo.

For now, the boom props up the broader economic expansion as well, offsetting the drag on the economy created by the random chaos-monkey actions of the White House. The boom employs engineers, fills order books at NVIDIA and TSMC, and underwrites consulting and cloud. But the question remains unanswered: is this a genuine revolution, or a stall-speed economy kept aloft by trillion-dollar engines that may never deliver thrust? The veil of time and ignorance still hides the answer. Like all great speculative buildouts, it is enriching the pick-and-shovel sellers, terrifying the horse-and-buggy incumbents, and leaving the rest of us waiting with baited breath to see which of the many promised futures (if any) will, in fact, arrive.