“The IMF’s maximum credit to Argentina… is projected to reach 1,352% of the country’s quota in 2026. This would be the Fund’s largest exposure in absolute terms in its history.”

Before we get to the meat of this story, let’s begin with a wee refresher. On April 11, as readers may recall, Argentina’s faux libertarian President Javier Milei gave a televised address to the nation. Flanked by his senior cabinet members, Milei told the Argentine people that his government had finally lifted the currency controls that had plagued the economy since 2011 so that people can once again buy dollars unhindered.

Economic stability, he said, had finally returned to the country — all thanks to another, ahem, IMF bailout, Argentina’s 23rd since becoming a member of the fund in 1956.

The latest $42 billion injection — $20 billion from the IMF, $12 billion from the World Bank and $10 billion from the Interamerican Development Bank — was intended to artificially prop up the peso in the months leading up to mid-term elections in October. But the peso is already in freefall, and the elections are just two months away.

As I noted at the time, this was the first time, to my knowledge that an Argentine government, or indeed any national government, had responded to a bailout from the IMF — an institution that Milei had described as “perverse” before his election as president — with jubilant celebration:

Normally, an IMF bailout is the last resort for a government that has run out of options as well as a source of great shame, not the beginning of a new golden age or the source of great pride, as the Milei government is trying to present it.

The fact that the Milei government is filled with pseudo-libertarians to whom the IMF should be anathema makes it all the more surreal. Argentina’s Finance Minister Luis Caputo, a serial debtor and former JP Morgan Chase banker who already burdened Argentina with a $57 billion IMF loan in 2018, even thanked his wife and children for their support during the negotiations, as if he were winning a lifetime award.

At the same time, some senior IMF staffers were so opposed to the deal that they were willing to walk away from their jobs.

Milei’s faster-than-expected lifting of currency controls was initially celebrated on Wall Street. Milei “is moving full speed ahead toward cleaning up Argentina’s decades-old macroeconomic mess,” investment bank UBS wrote. “The elimination of capital controls, and the strengthening of the fiscal anchor, have all surpassed even the rosiest analyst expectations.”

Time to “Take a Breather”: JP Morgan Chase

Despite all the talk of removing currency controls, there are clear exchange rate bounds for the dollar (between $1,000 and $1,450). Initially, the peso performed reasonably well, given that citizens and businesses were finally able to buy unlimited sums of dollars — albeit only digitally (the controls on cash are, if anything, tighter than before) — and send them overseas.

Pressures, however, have gradually risen, as the peso has moved closer and closer to the $1,450 upper bound. Meanwhile, increasing doubts have set in among international investors, reports Buenos Aires Herald:

´[A] JP Morgan report, titled “Argentina: Taking a breather,” suggested taking profits in long [Argentine bonds, or] LECAPs. Although the financial institution remained “constructive on Argentina’s medium-term prospects given disinflation and fiscal progress,” it warned about potential issues — namely, the fact that “peak agricultural inflows” have past, likely continued tourism outflows, potential election noise, and the Argentine peso’s underperformance, which prompted the Central Bank to intervene in the foreign exchange market via derivatives.

“With positive seasonality close to an end and elections looming, we prefer to take a step back and wait for better entry levels to re-engage in bullish local markets trades,” the report said.

In April, the firm had recommended that investors participate in short-term carry trades in Argentina after the administration lifted several capital restrictions for individuals and companies. However, in last week’s report, they said that “recent developments warrant a more cautious approach in the near term.”

The lifting of the currency controls at the behest of the IMF has enabled investors to get the money out of the country, just as happened in the 2018 bailout. In April and May, the first two months following this year’s bailout, USD 5.247 billion left the country, reports Perfil. That is equivalent to 44% of the first instalment of $12 billion issued by the IMF. This is a feature, not a bug, of IMF bailouts.

“The level of outflows in May exceeded the monthly averages of all the years of the exchange balance series prepared by the Central Bank of the Republic of Argentina — that is, from 2003 to date,” warns the Center for Research and Training of the Argentine Republic in a recent study. “It is even higher than the monthly average of 2018 and 2019, when the valuation of financial assets collapsed during the Macri government.”

If you combine the figures from April and May with the estimates from June, around $10 billion has left the country in just three months, notes the economist and former president of Banco Nación, Carlos Melconian. To put that in perspective, Argentina’s entire annual energy trade surplus is around $12 billion.

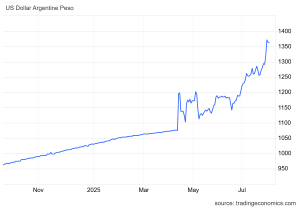

As hot money leaves the country, the pressures are building on the Argentine peso. In June, the official dollar exchange rate rose sharply. In July, the rise went almost vertical: 14% in just one month.

Last Thursday, as Bloomberg reported, the peso dropped more than 4.4% in just one day, making it the worst performer in emerging markets and rounding off a woeful month for the Argentine currency:

It has tanked by more than 12% in July, the worst monthly decline since Milei devalued it after taking office in December 2023.

The government has been building up international reserves in July, pushing pesos into the economy, amid pressure to meet goals of its program with the International Monetary Fund. The market has also seen increased demand from the private sector as businesses seek cover in the greenback ahead of October mid-term elections.

A central bank report shows dollar purchases rising in June by more than $800 million to total around $4 billion, with the number of Argentines buying foreign currency almost doubling the amount of those selling it.

“Grab the Pesos and Buy US Dollars”

The irony is that this comes just weeks after Economy Ministry Luis Caputo disparaged analysts for daring to suggest that the government has been artificially propping up the peso in a bid to contain inflation, which is exactly what it’s been doing since December 2023. The two main drivers behind Milei’s success in bringing down inflation are: a) his government’s austerity-on-angel dust program; and b) the artificial cheapening of the dollar.

This latter approach has not only made Argentina the most expensive country in Latin America in dollar terms while destroying the competitiveness of the country’s manufacturers; it has also burnt through tens of billions of dollars of central bank reserves while generating easy profits for financial speculators. It is also wholly unsustainable, as we warned in December. As Philip Pinkerton notes, the moment the economy started to grow again import demand began surging and the peso came under renewed pressure.

7/ But now that the economy is starting to grow again import demand is surging and the peso is coming under renewed pressure. Markets are taking notice. pic.twitter.com/yTMnc4C0rD

— Philip Pilkington (@philippilk) July 7, 2025

Now, back to Economy Minister (and former JP Morgan Chase banker) Luis Caputo.

“To anyone who thinks [the dollar] is that cheap, grab the pesos and buy [U.S. dollars],” Caputo said sarcastically a few weeks ago. “Don’t miss out on it, champ. If you have pesos, the exchange rate is free-floating, and you know for a fact it is very cheap, go ahead and buy”.

And that is what many have done. From that moment, the exchange rate has surged by AR$135, almost 11%. As the FT reports, the sinking peso presents Milei with a thorny dilemma:

The potent peso is policy. Milei is betting it will help him achieve the goal on which he has staked his political reputation: killing inflation. Argentina holds midterm elections in October and although last month’s inflation was the lowest in five years, prices are still up 43 per cent year on year.

Faced with a dilemma between reducing inflation, boosting growth or building reserves and stabilising the exchange rate, “the government prioritised inflation, which is politically the most profitable, at the expense of the others,” said Eduardo Levy Yeyati, an economist and professor at Torcuato di Tella university in Buenos Aires. “Now the other areas are screaming for attention.”

With the peso about 40 per cent stronger against the dollar in real terms, imports have surged, small businesses are struggling and unemployment has jumped to a four-year high. Despite Milei’s oft-professed desire to transform statist Argentina into a beacon of free markets, chief executives are not opening their wallets.

As the dollar rises, the risk of a sharp resurgence in inflation rises. Prices are already surging at the checkout, reports Perfil. Milei’s response has been to double down on his chainsaw austerity.

If necessary, more IMF dollars will have to be auctioned by the Treasury in an increasingly futile attempt to keep the rising dollar at bay. Meanwhile, public sector wages and pensions will remain frozen for the foreseeable. The economic pain will have to intensify until the economy stabilises — in a country where around 50% of the population are already having difficulty making ends meet as prices continue to rise while wages stagnate, according to a survey by Moiguer.

With consumer demand already anaemic, even large corporations are beginning to complain, reports Página 12:

They say that five large companies came knocking on the Minister Caputo’s door. “We are unable to sell, with these high prices. In the long run, we’re going to have to fire people. In fact, some are already doing it,” executives from two large food companies and envoys from the automakers Toyota and Ford told him. “The President is not interested in these issues,” the minister replied, with some embarrassment.

Caputo must have said something similar, and in the same terms, to a senior leader of the Argentine Industrial Union (UIA) of a province in the interior. This week, its head, Martín Rappallini, used official numbers to say that the country’s factories are losing 1500 jobs per month due to the drop in activity.

The Geopolitical Dimensions of Argentina’s Debt Crisis

In a recent speech in Colombia, the US economist Joseph Stiglitz warned that history is once again repeating in Argentina. Stiglitz recounted that in 2018 then-President Mauricio Macri had applied for bailout funds in excess of $44 billion, which the Fund duly approved. It was the Fund’s largest ever bailout, which has now been beefed up by a further $20 billion.

Just as now, the rescue package was awarded during the lead-up to key elections, which Macri ended up losing. Just as now, currency controls were temporarily lifted, allowing investors, domestic and foreign, to get their money out of the country before things got ugly, which is exactly what happened.

As Stiglitz notes, Argentina “could not pay the 44 billion dollar loan (from 2018), yet now the IMF is lending them an additional $20 billion that they will also be unable to pay. This is presumably the reason why some senior IMF staffers were so opposed to the deal that they were willing to literally walk away from their jobs, as La Política Online (LPO) reported (machine translated):

The opposition this situation generated among the organisation’s staff led to the firing/resignation of several senior managers. First was the Chilean economist Rodrigo Valdés, who as director of the Western Hemisphere was naturally in charge of the Argentine case. Valdés is a consistent critic of Argentina’s hyper-indebtedness favoured by the Fund.

And now it has emerged that Turkey’s Ceyla Pazarbasiogluel, the director of the IMF’s Strategy, Policy and Review Department (SPR), refused to sign off on the new loan. In her place, two minor officials intervened to trigger the loan. “Totally outside the manual,” the Fund itself acknowledged to LPO.

The SPR is known as the “alpha male” of the IMF’s departments, or the IMF’s “politburo” — metaphors that illustrate its enormous power behind the scenes, since no major report can be published without its approval, as a former member of that committee revealed in an article in the Financial Times.

Yet resistance was overcome, presumably because Washington wanted it this way.

As readers may recall, just three days after the joint IMF-World Bank-Interamerican Development Bank bailout was announced, US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent visited Argentina. As we reported at the time, the most likely motive for the visit was to impress upon the Milei government the importance of reducing Argentina’s economic dependence on China, currently its second largest trade partner.

Just weeks before Bessent’s visit, the US State Department’s head of Latin America, Mauricio Claver-Carone, was in Argentina, where he cited the ending of Argentina’s swap line with China as a key condition for an explicit endorsement of the Trump administration for the IMF bailout.

“We want to make sure that no agreement with the Monetary Fund ends up prolonging that line of credit or that swap they have with China,” said Claver-Carone. “If we do that, we are shooting ourselves in the foot.”

This is a reminder of just how important a role the IMF often plays in geopolitics — a role that is only likely to grow in the coming years as the US seeks to reinsert control over its own back yard. In 2020, Claver-Carone, in the same role for the first Trump Administration, openly admitted that the US’s decision to grant the $57 billion loan (of which only $44 billion was ultimately used) requested by Mauricio Macri’s government in 2018 was largely based on geopolitical considerations.

Back to today, Argentina has an additional economic sword of Damocles hanging over its head. In late June, US District Court Judge Loretta Preska ordered the Argentine State to turn over its 51% stake in the oil and gas company YPF to partially satisfy a $16.1 billion court judgment brought by litigation funder Burford Capital. As Reuters relates, the case centres on Argentina’s 2012 forced nationalisation of Spain’s Repsol’s 51% stake in YPF without placing a tender offer to minority shareholders Petersen Energia Inversora and Eton Park Capital Management.

YPF is one of Argentina’s main sources of foreign currency, and the Milei government has appealed the decision, warning that the stakes could not be higher. If Judge Preska’s ruling is upheld, it says, it would irreparably harm its sovereignty, destabilize the Argentine economy and cause the irrevocable loss of a controlling stake in the country’s largest energy company. For the moment, the US government has sided with Argentina’s efforts to put the court order on temporary hold but the sword continues to hang.

In the meantime, the IMF’s exposure to Argentina’s almost constantly ailing economy continues to grow. The Fund’s maximum credit to the country is projected to reach 1,352% of the country’s quota in 2026, making it the Fund’s largest exposure in absolute terms in its 81 year history. What happens the next (and 24th) time Argentina defaults on its obligations, time may soon tell.