Job creation slows, dementia-addled chaos-monkey tariff risks continue, data-center construction booms with little ability to rapidly move resources into that part of the construction-investment sector, and so the likelihood of stagflation in the near-term future rises. The U.S. economy is growing, but no longer fast enough to clearly outrun the shadow of rising unemployment, and yet inflation risks driven by supply and narrow sector-bottleneck shocks rise as well…

Job creation in the U.S. has slowed to a crawl, with recent months averaging just 35,000 new payrolls—a figure well below what’s needed to keep unemployment from rising. Yet inflation risks are not falling but growing, stubbornly present, amplified by dementi-addled chaos-monkey tariff-shock and other supply-chain uncertainties, plus sectoral-investment surges that may well run into inflation-producing bottlenecks. With Federal Reserve policymakers now publicly divided and the macroeconomy below stall speed, the risks of policy missteps and unexpected shocks loom large. The macro stakes are high.

This AM we have the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics:

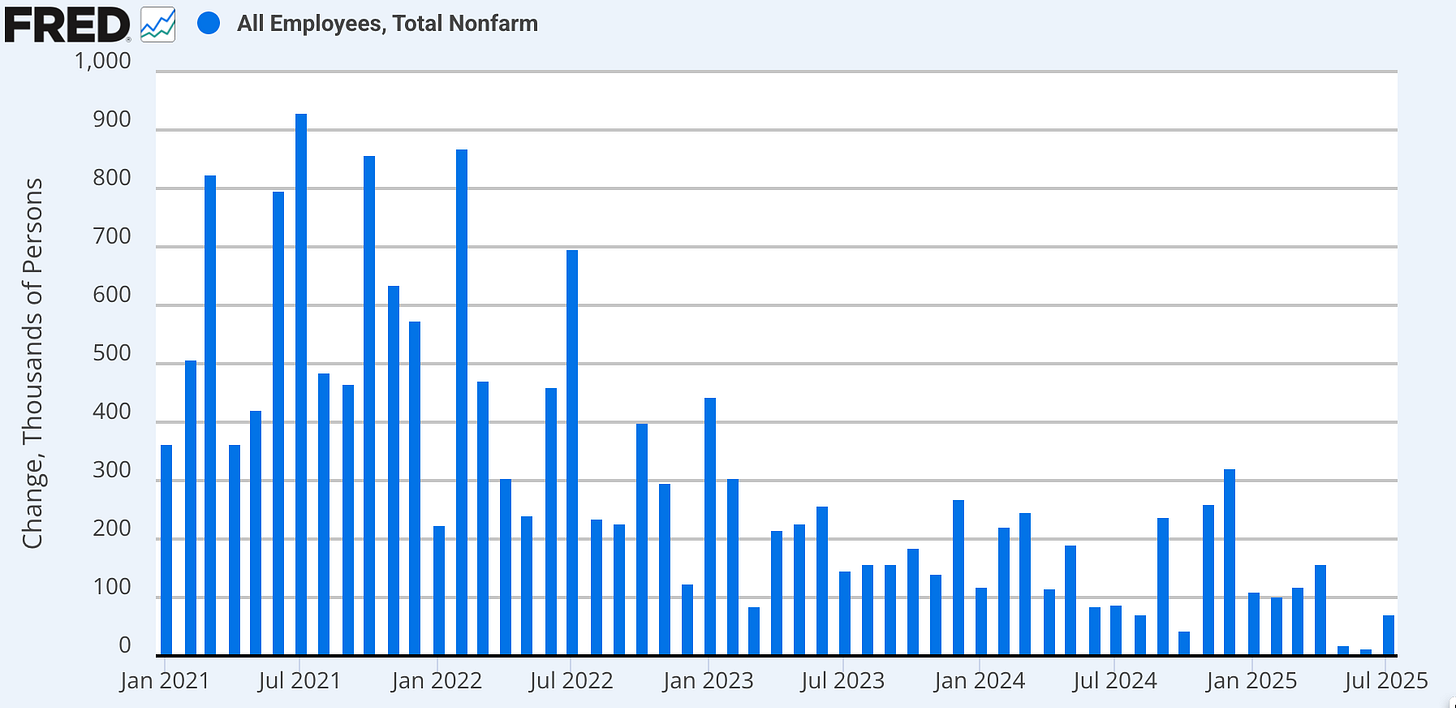

BLS: Employment Situation Summary <https://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.nr0.htm>: ‘Transmission of material in this news release is embargoed until 8:30 a.m. (ET) Friday, August 1, 2025…. JULY 2025: Total nonfarm payroll employment changed little in July (+73,000) and has shown little change since April…. The unemployment rate, at 4.2 percent, also changed little in July. Employment continued to trend up in health care and in social assistance.… The unemployment rate has remained in a narrow range of 4.0 percent to 4.2 percent since May 2024…. The number of long-term unemployed (those jobless for 27 weeks or more) increased by 179,000 to 1.8 million… 24.9 percent of all unemployed people….

Revisions for May and June were larger than normal. The change in total nonfarm payroll employment for May was revised down by 125,000, from +144,000 to +19,000, and the change for June was revised down by 133,000, from +147,000 to +14,000. With these revisions, employment in May and June combined is 258,000 lower than previously reported…

With:

-

Over the past three month—only 106,000 new payroll jobs, seasonally adjusted; that is only 35,000 per month.

-

Since the end of last year—only 597,000 new payroll jobs, seasonally adjusted; that is only 85,000 per month.

(2) may, actually, not be a slow-enough rate of growth of payroll unemployment to put upward pressure on the unemployment raite and thus on the difficulty of finding a job. Jared Bernstein quotes Jed Kolko on this point:

Jed Kolko: 25-5 As US Population Growth Slows, We Need to Reset Expectations for Economic Data <https://www.piie.com/sites/default/files/2025-07/pb25-5.pdf>: ‘US population growth has slowed sharply in the past 18 months, as the immigration surge of the early 2020s has ended and the population continues to age. Fewer jobs are needed to keep up with the growth of the labor force…I estimate the breakeven rate of monthly payroll growth in the jobs report needed to keep up with the labor force has fallen from 166,000 jobs in early 2024 to 86,000 jobs in June 2025…

Smack-equal to what we have seen so far in 2025. An economy not at stall speed for the year as a whole so far, but worryingly close, and slowing down significantly over the past three months.

And Jared Bernstein—very sharp, but who, since he had worked for Biden since 2009, is one of those really ought back in 2022 to have been telling me to start pushing hard for a new candidate for president, and did not—summing up the sitch:

Jared Bernstein: Job Creation Slows To A Crawl: Monthly Avg: 35,000 over Past 3 Months <https://econjared.substack.com/p/job-creation-slows-to-a-crawl-monthly>: ‘The big news is the payroll revisions… “employment [growth] in May and June combined is 258,000 lower than previously reported.”… [Plus} manufacturing employment is down three-months in row…. US manufacturing depends on imported inputs… [so] Trump’s escalating trade war exacerbates this…. Kicking up the effective tariff rate to somewhere around 18%… will hurt, not help, our manufacturers….

A few brighter spots: —Wage growth remains solid, at 3.9%, handily beating inflation. —Layoffs have been slowly trending up, but we’ve yet to see a spike that’s commensurate with severe labor market deterioration.

Chris Waller was one of the dissenters on the Fed’s decision earlier this week to hold interest rates where they are. One of Waller’s key motivators for cutting rates is his view that the labor market is weakening… “while the labor market looks fine on the surface… downside risks to the labor market have increased. With inflation near target and the upside risks to inflation limited, we should not wait until the labor market deteriorates before we cut the policy rate….” Chair Powell… took the other side… repeatedly describing the labor market as solid…. Today’s report obviously leans Waller’s way…. But… slower labor supply… deportations and considerably slower immigration….

Hard data—growth, jobs, inflation—are 1754070787 starting to show what happens when the economy is relentlessly subjected to destructive economic policy…

A word about Waller: I think it unprofessional right now to assert, unqualified, that “upside risks to inflation are limited.” The recent history of U.S. inflation should make everyone humble: we have seen how quickly how what we judge small transitory shocks—whether from supply chains, energy prices, or geopolitical disruptions—can morph into much larger cost pressures self-sustaining for a time, and threatening to exit the transitory mode for the persistent one. Plus a professional central banker must always keep a weather eye on all potential sources of risk, and never unduly minimize any of them.

To declare, as Waller did, that such risks are “limited” is to attempt to lull markets and policymakers into complacency—precisely the opposite of what a prudent monetary authority should do. At the very least the standard of professionalism would require a nuanced and conditional framing: “While recent data suggest upside risks to inflation are moderating, those risks could return—particularly if supply constraints return or if aggregate demand surprises to the upside.”

I would have liked to see something like: If the enormous uncertainty about future tariff increases were to be removed, then upside risks to inflation would be significantly reduced. The message that the Fed should be sending to Donald Trump right now is this: if you are serious about lower interest rates, give us policies that make a lower interest rate path prudent.

Fed Governors, even tempted to go the extra mile in currying favor with Donald Trump, perhaps out of hope that their fealty will land them in the big chair at the Federal Reserve—really should behave better. Remember Arthur Burns in the early 1970s, whose willingness to accommodate the Nixon administration’s political imperatives did lasting damage to the Fed’s credibility and amply watered and fertilized the sprouting Great Inflation of the 1970s. The central bank’s power is mostly a power of narrative and expectation management. Once the perception takes hold that policy is being tailored to the whims of the incumbent or the ambitions of a would-be Fed Chair, little can be done, and what can be done quickly becomes very costly. Fed Governors must always remember who their true constituency is: not the president du jour, but rather the long-term economic and financial heualth of the republic. Now matter what a corrupt Supreme Court may claim, Fed Governors have their 14-year terms precisely because they are not instrumentalities to carry out the whims of an underbriefed chaos-monkey executive-branch president with dementia, but rather independent technocratic powers making decisions about coining money and regulating the value thereof as directed by the congress.

All that is to say: A false claim that upside inflation risks are limited is not helpful.

Today, the sources of potential upside risk to inflation are not low: chaos-monkey dementia-fueled tariff craziness continued, renewed energy shock, a reversal in globalization, an unexpected fiscal expansion, or, as we are already observing, the AI-driven data-center construction boom that is channeling a torrent of investment into the real economy. Central bankers need to never dismiss these risks out of hand, but to take the prudent course, which is to acknowledge uncertainty and to keep all options on the table, rather than to lull the polity into a false sense of security that may soon prove costly.

And yet, that said: Waller has, I think, a sound desire to become Fed Chair. rooted both in personal ambition and in a genuine conviction that, among the names likely to appear on a hypothetical Trump short list, he would be the most responsible and competent steward of U.S. monetary policy. In my view, he is correct. I would breathe somewhat easier, at a disaster (probably) averted, if Waller were to become Fed Chair next year. Waller is not like those whom one might politely call “mercurial” or “ideologically-driven” who might catch Trump’s chaos-monkey dementia-addled eye. He has the analytic and procedural norms that keep monetary policy on an even keel in his bones. The prospect of someone with his background and temperament at the helm is, in this fraught moment, a source of some comfort—if, admittedly, of only some and rather cold comfort.

A note on one of the things creating upside inflation risks right now:

Consider the sheer magnitude of the data-center construction boom fueled by the current AI bubble.

This is a phenomenon that, I think, deserves far more attention from both policymakers and market-watchers. The scale is staggering. Over the four years 2024-2027 we now expect to see more than $1.8 trillion spent building not bricks-and-mortar but rather generator, wire, silicon, plywood, concrete, pipe, and steel data centers worldwide. The hyperscalers and others are each pouring tens of billions of dollars into new facilities globally, in a frantic bid to secure the computational horsepower and energy infrastructure needed to train and deploy ever-larger natural-language models. This is not your garden-variety tech cycle; it is a capital expenditure arms race, and the urgency is driven less by exuberant optimism for future profits than by a defensive fear—fear that failing to provide customers with the lowest-latency inference and the highest-quality training will mean irrelevance in the next platform transition.

The result is a wave of demand for construction labor, steel, concrete, specialized semiconductors, and, most crucially, power—already putting upward pressure on input prices in regions like northern Virginia, Texas, and the Pacific Northwest. Historically, such sectoral investment booms have had the power to push up wages and prices even in the absence of broad-based consumer-demand surges. The AI data-center surge is not a sideshow: it is a macroeconomic force that could well become a significant contributor to inflation dynamics in the quarters ahead, and one that the Fed ignores at its peril.

The investment triggered by other bubbles died off as businesses saw themselves as unlikely to make profits from further investments, even with the extraordinary investment-financing terms that the bubble’s irrational exuberance offered them…

Not this time: these AI data-center investments are defensive insurance, not attempts to massively grow their profits. That is, unlike the dot-com or fiber-optic booms of the late 1990s, or the shale oil bonanza of the 2010s, the current wave of capital expenditure is less about chasing speculative upside than about preempting existential risk. The buidlers are not betting on blue-sky demand projections or the hope that “if we build it, they will come.” Instead, they are acting out of fear that, should they fail to keep pace in providing the lowest-latency inference and the highest-quality model training, they will be left behind in the next technological paradigm shift. This is primarily a race to avoid irrelevance and the loss of their current tech oligopoly-platform profits, not to seize new territory.

The result is a remarkable stickiness to investment, even as financing costs have risen and macro uncertainty abounds. The willingness to sign multi-year power purchase agreements, lock in supply chains for specialized semiconductors, and pre-commit to massive construction contracts all reflect this insurance logic. It is a dynamic that, I think, makes the potential inflationary potential of the current boom more persistent and less susceptible to the usual self-correcting mechanisms that have tamed previous bubbles.

And the magnitude of this bubble-driven boom has a consequence. Normally I would react to a jobs report like this by stating that there is now at least a 50-50 chance of a near-term recession. But not this time. I cannot make any sort of likely recession call—not with this going on.