Yesterday, the Reserve Bank of Australia finally lowered interest rates some months after it became clear the economy is slowing and the labour market is getting weaker. The RBA remain fixated on there claims that wages growth is too high. In yesterday’s – Statement by the Monetary Policy Board: Monetary Policy Decision ((August 12, 2025) – they claimed that the “labour market remains a little tight” and that “Measures of labour underutilisation nevertheless remain at low rates” – which must be them rehearsing for careers as comedians. Unemployment is rising quickly and the broad underutilisation rate was at 10.3 per cent. So for the RBA having 10.3 per cent of available labour not being used in one way or another is a ‘low rate’. Extraordinary. Anyway today (May 14, 2025), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest – Wage Price Index, Australia – for the June-quarter 2025, which shows that the aggregate wage index rose by 3.4 per cent over the 12 months and is steady. The June-quarter 2025 nominal wage growth outpaced the standard inflationary measures. While most commentators will focus on the nominal wages growth relative to CPI movements, the more accurate estimate of the cost-of-living change is the Employee Selected Living Cost Index, which is still running well above the CPI change. Using that measure, purchasing power of the nominal wages grew modestly in the June-quarter after several quarters of zero or negative growth. However, there is no wages breakout evident. And while the RBA are fixated on low productivity, they fail to demand more investment from the business community which is the main reason for lagging productivity.

While most commentators will focus on the nominal wages growth relative to CPI movements, the more accurate estimate of the cost-of-living change is the Employee Selected Living Cost Index, which is still running well above the CPI change. Using that measure, purchasing power of the nominal wages was stable in the March-quarter. There is no wages breakout happening.

Latest Australian data

The Wage Price Index:

… measures changes in the price of labour, unaffected by compositional shifts in the labour force, hours worked or employee characteristics

Thus, it is a cleaner measure of wage movements than say average weekly earnings which can be influenced by compositional shifts.

The summary results (seasonally adjusted) for the June-quarter 2025 were:

| Measure | Quarterly (per cent) | Annual (per cent) |

| Private hourly wages | 0.8 (-0.1 point) | 3.4 (+0.1 point) |

| Public hourly wages | 1.0 (steady) | 3.7 (+0.1 point) |

| Total hourly wages | 0.8 (steady) | 3.4 (steady) |

| Employee Selected Cost-of-Living measure | 0.4 (-0.7 points) | 2.6 (-0.8 points) |

| Basic CPI measure | 0.7 (-0.2 points) | 2.1 (-0.3 points) |

| Weighted median inflation | 0.6 (-0.1 point) | 2.7 (-0.2 points) |

| Trimmed mean inflation | 0.6 (-0.1 point) | 2.7 (-0.2 points) |

On price inflation measures, please read my blog post – Inflation benign in Australia with plenty of scope for fiscal expansion (April 22, 2015) – for more discussion on the various measures of inflation that the RBA uses – CPI, weighted median and the trimmed mean.

The latter two aim to strip volatility out of the raw CPI series and give a better measure of underlying inflation.

The ABS press release – Wages rise 3.4% in the year to June 2025 – notes that:

The Wage Price Index (WPI) rose 0.8 per cent in the June quarter 2025 and 3.4 per cent annually …

Annual wage growth to the June quarter 2025 was unchanged from the 3.4 per cent rise seen in the March quarter 2025 but was down from the 4.1 per cent growth at the same time last year …

The smaller proportion of jobs with larger wage increases has contributed to lower overall wage growth …

Both the private and the public sectors had lower annual wage growth compared to the June quarter 2024.

Summary assessment:

1. Wages growth is stable – no outbreak evident despite the RBA claiming their much vaunted (by the RBA) “business surveys and liaison” meetings are claiming things are tight.

The business community is always trying to frame the situation as a ‘labour problem’ where wages growth is excessive.

The RBA should cancel these meetings given they rarely say anything different from month to month.

2. Over the 12-month period there was a modest improvement in the real purchasing power of nominal wages using both the CPI and the Employee Selected Cost-of-Living Index measures, which is a good outcome for workers.

See below for a discussion about the most appropriate cost-of-living measure to deploy (see below).

4. Over the last 20 quarters, there have been only five that have delivered real wages growth using the Employee Selected Cost-of-Living measure – so the latest result is a positive sign.

Inflation and cost of living measures

There is a debate as to which cost-of-living measure is the most appropriate.

The most used measure published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is the quarterly ‘All Groups Consumer Price Index (CPI)’.

Reflecting the need to develop a measure of ‘the price change of goods and services and its effect on living expenses of selected household types’, the ABS began publishing a new series in June 2000 – the Analytical Living Cost Indexes – which became a quarterly publication from the December-quarter 2009.

In its technical paper (published October 27, 2021) – Frequently asked questions (FAQs) about the measurement of housing in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Selected Living Cost Indexes (SLCIs) – the ABS note that:

The CPI and SLCIs are closely related. All these indexes measure changes in prices paid by the household sector (consumers) for a basket of goods and services provided by other sectors of the economy (e.g. Government, businesses). The weights in the ‘basket’ represent amounts of expenditure by households on goods and services bought from other sectors. Goods traded between households (like buying and selling existing houses) are excluded as both sides of the transaction occur within the household sector.

I discuss these indexes in detail in this blog post – Australia – real wages continue to decline and wage movements show RBA logic to be a ruse (August 16, 2023).

In effect, the SLCIs represent a more reliable indicator of ‘the extent to which the impact of price change varies across different groups of households in the Australian population’.

There are four separate SLCIs compiled by the ABS:

- Employee households.

- Age pensioner households.

- Other government transfer recipient households.

- Self-funded retiree households

The most recent data – Selected Living Cost Indexes, Australia – was published by the ABS on August 6, 2025 for the June-quarter 2025.

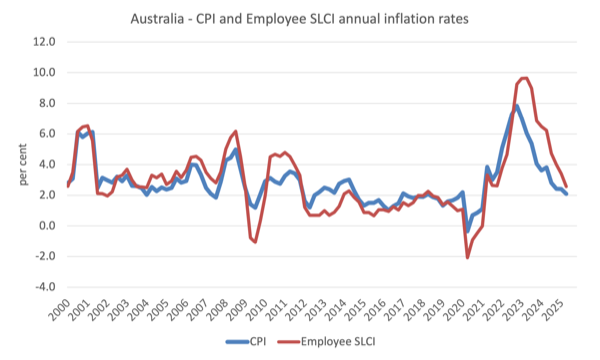

The following graph shows the differences between the CPI-based measure and the Employee SLCI measure which better reflects the changes in cost-of-living.

Thus, when specific household expenditure patterns are more carefully modelled, the SLCI data reveals that the cost-of-living squeeze on ‘employee households’ is more intense than is depicted by using the generic CPI data.

The ABS considers the ‘Employee households SLCI’ to be its preferred measure designed to capture cost-of-living changes more accurately for ‘households whose principal source of income is from wages and salaries’.

Summary of Real Wage Movements

- The relevant cost-of-living measure for workers has risen by 2.6 per cent whereas the CPI rose by 2.1 per cent over the last year.

- While workers enjoyed a purchasing power gain in the June-quarter, it was obviously lower using the correct deflator as the relevant cost-of-living indicator.

- The media, however, always focus, wrongly, on the CPI as the relevant inflation measure and thus inflate the real wage gains.

Real wage trends in Australia

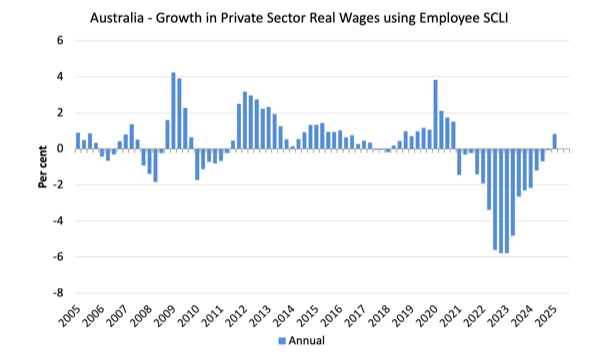

The summary data in the table above confirms that real wages growth overall (private and public sectors) has finally turned positive after 15 previous quarters of declining purchasing power.

The following graph uses the Employee SLCI measure to show the movement of real wages in the private sector from 2005 to the March-quarter 2024.

The fluctuation in mid-2020 is an outlier created by the temporary government decision to offer free child care for the March-quarter which was rescinded in the March-quarter of that year.

Overall, the record since 2013 has been appalling.

Throughout most of the period since 2015, real wages growth has been negative with the exception of some partial catch-up in 2018 and 2019.

Workers have only been able to secure partial offset for the cost-of-living pressures caused by the supply-side, driven inflation.

The great productivity rip-off continues

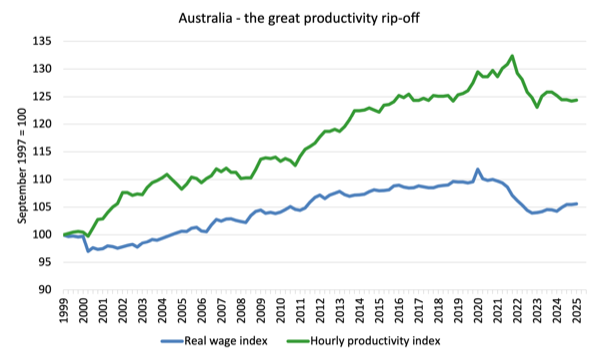

While the decline in real wages means that the rate of growth in nominal wages is being outstripped by the inflation rate, another relationship that is important is the relationship between movements in real wages and productivity.

As part of their attempt at justifying the interest rate hikes, the RBA were also making a big deal of the fact that wages growth is too high relative to productivity growth.

Historically (up until the 1980s), rising productivity growth was shared out to workers in the form of improvements in real living standards.

In effect, productivity growth provides the ‘space’ for nominal wages to grow without promoting cost-push inflationary pressures.

There is also an equity construct that is important – if real wages are keeping pace with productivity growth then the share of wages in national income remains constant.

Further, higher rates of spending driven by the real wages growth can underpin new activity and jobs, which absorbs the workers lost to the productivity growth elsewhere in the economy.

The Treasury likes to use the Real Unit Labour Costs (also equivalent to the wage share in income) as the measure of business costs.

It is the ratio of real wages to labour productivity.

From the March-quarter 2020 until the September-quarter 2024, RULCs growth was negative, which means there was a major redistribution of national income going away from wages to profits.

In the last 3 quarters, there has been positive but modest growth.

However, this has largely occurred because productivity growth has been negative.

So it is really lagging productivity growth that is the culprit and that reflects on management decisions (investment, innovation, etc) rather than trade unions forcing excessive wage increases.

Nominal wages growth is anything but excessive.

We can see that in the following graph which shows the total hourly rates of pay in the private sector in real terms deflated with the CPI (blue or lower line) and the real GDP per hour worked (from the national accounts) (green or upper line) from the June-quarter 1999 to the June-quarter 2025.

It doesn’t make much difference which deflator is used to adjust the nominal hourly WPI series. Nor does it matter much if we used the national accounts measure of wages.

But, over the time shown, the real hourly wage index has grown by only 5.6 per cent, while the hourly productivity index has grown by 24.4 per cent.

The dip in productivity growth is due to the parlous investment rates of Australian businesses.

If I started the index in the early 1980s, when the gap between the two really started to open up, the gap would be much greater. Data discontinuities however prevent a concise graph of this type being provided at this stage.

For more analysis of why the gap represents a shift in national income shares and why it matters, please read the blog post – Australia – stagnant wages growth continues (August 17, 2016).

Where does the real income that the workers lose by being unable to gain real wages growth in line with productivity growth go?

Answer: Mostly to profits.

These blog posts explain all this in more technical terms:

1. Puzzle: Has real wages growth outstripped productivity growth or not? – Part 1 (November 20, 2019).

2. Puzzle: Has real wages growth outstripped productivity growth or not? – Part 2 (November 21, 2019).

Conclusion

In the June-quarter 2025, Australia’s nominal wage growth grew by 3.4 per cent, which outpaced the standard inflationary measures.

While most commentators will focus on the nominal wages growth relative to CPI movements, the more accurate estimate of the cost-of-living change is the Employee Selected Living Cost Index, which is still running well above the CPI change.

Using that measure, purchasing power of the nominal wages grew modestly in the June-quarter after several quarters of zero or negative growth.

Upcoming Event: A New Economic Vision for the Labour Movement, Friday, August 15, 2025

I will be talking at an event in Melbourne this Friday organised by the Unionists for a Job Guarantee.

My session begins at 11:00 although the overall event starts at 9:30.

It will be held at the Victorian Trades Hall, 2-40 Lygon St, Carlton VIC 3053, Australia.

All are welcome, free entry.

Full details – https://www.facebook.com/events/1760888248131115/

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.