We knew in the 1980s, when neoliberal-influenced governments started selling of public trading enterprise for not much that the strategy would not deliver on its promises. At least some of us knew and wrote about it then. I was part of a team that analysed the disasters that would follow the sell off of the Commonwealth Bank and Qantas. Qantas, by the way, has gone through a sequence of high profile scandals, including selling tickets for flights it had already cancelled, illegally sacking workers during COVID, and other demonstrations of incompetent and capricious management. Just this week, it was fined $A90 million for the illegal sacking of the baggage handlers. The latest demonstration of how privatisation has failed is the revelation that the child care industry in Australia has become a honey pot for paedophiles and sociopaths as for-profit child care centres pursue profit at the expense of caring for the children in their centres. The solutions are always straightforward but rejected by governments – bring these activities back into the not-for-profit state sector. Meanwhile, the future of tens of thousands of children are being compromised by profit greed as governments wax lyrical about how much they care for the kids but do very little to stop the abuse.

Background

The – Child Care Act 1972 – marked a turning point in government responsibilities for this sector.

It was legislated by a conservative government in the last months of its tenure – a period marked by growing social turmoil (particularly surrounding our involvement in the Vietnam War) and massive social changes (particularly with respect to the role of married women in the workforce).

An article in the Australasian Journal of Early Childhood (December 2013, Vol 38, No 4) – The Child Care Act 1972: A critical juncture in Australian ECEC and the emergence of ‘quality’ – notes that:

The Act contained legislation for ‘the beginning of the Commonwealth government’s large-scale involvement’ in funding Australian child care … Although the Act was introduced primarily to facilitate women’s workforce participation, its content reflected an understanding that government intervention was necessary to address the quality of child care.

It was understood that a highly regulated model would be required to ensure “the provision of high-quality child care” at an affordable price to households.

The authors also note that:

The Act explicitly promoted factors contributing to quality, such as funding for the development of approved childcare facilities and encouraging the employment of staff with qualifications related to early childhood education and/or health.

Well-paid careers for highly qualified staff were created and sustained.

The funding was targetted at not-for-profit centres, which were usually run by community-based organisations and charities.

Centres had to employ staff with appropriate qualifications and many people with formal teaching qualifications entered the sector.

It was always understood that childcare possessed the characteristics of a Public good – which was used to justify the government funding and regulative framework.

The neoliberal era begins

However, that changed in the 1980s and into the 1990s, as neoliberal swept through the policy making process.

This Interview – Childcare: where we came from and where we’re going – is interesting in tracing the decline of the sector as successive governments diverted the funding to the ‘Private for profit’ corporations entering the childcare industry.

The situation has worsened since that interview was published (2009).

The relentless push for ‘market-based’ service delivery followed the privatisation of the public trading enterprises in the 1980s.

The early privatisations were in the areas covered by public banks, airlines, and the utilities.

Much was promised by the results have demonstrated how selling these public activities to profit-seeking corporations has been very costly to the well-being of the public.

Later, the attention shifted to the provision of human services, which is obviously a core responsibility of the public sector.

In Australia, the – Productivity Commission – is a neoliberal, pro-market government agency in Australia that examines big microeconomic issues.

Its origins come from the old Tariff Board, which was founded by the federal government in 1921 as part of the strategy to develop a manufacturing industry behind a tariff wall, using the – Infant industry – justification.

In 1974, as the use of tariffs to protect industry were becoming maligned (by the free traders who basically wanted open slather), the government changed the name to the Industries Assistance Commission, which then became the Industry Commission in 1990 and was folded into the Productivity Commission in 1998, along with two research bureaus – the Bureau of Industry Economics (BIE) and the Economic Planning Advisory Commission (EPAC).

Staff were purged in these shifts to create a full-blown neoliberal attack dog.

So, starting out as a body that administered the trade protection policy of the Federal government in the C20th, the Productivity Commission has morphed into its current guise, which is to give advice to government on how to deregulate, privatise, outsource and otherwise trash the conditions of workers.

It evolution reflects the way in which the economics profession has evolved over the time span involved.

On December 5, 2016, the Productivity Commission (PC) released its report – Introducing Competition and Informed User Choice into Human Services: Reforms to Human Services – which subsequently informed huge changes in the provision of human services in Australia.

However, while the PC claimed that ‘user choice’ “empowers users of human services to have greater control over their lives and generates incentives for providers to be more responsive to their needs”, which is just standard ‘free market’ rhetoric, they did warn that:

Competition and contestability are means to this end and should only be pursued when they improve the effectiveness of service provision.

In the case of the childcare sector, such a warning has been ignored by both state and federal governments over many years as the litany of failures continued to grow.

The regulator of the childcare services in Australia – Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority – is charged with “administering the National Quality Framework (NQF) for children’s education and care.”

It recently released the latest – National Quality Framework (NQF) Snapshots (published July 1, 2025) – which are quarterly reports on “the progress and results of quality assessment and rating against the National Quality Standard (NQS)”.

Together with the accompanying data – NQS time series data (Q3 2013 – Q2 2025) – we can piece together a sorry tale of appalling failure.

The following table shows some aspects of the childcare sector in Australia.

Data was first published by the ACECQA in the September-quarter 2013 and the most recent quarter is June 2025.

The NQF classifies centres into ‘management type’ using the framework developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics – National Early Childhood Education and Care Collection: Data Collection Guide, 2013.

| Period | Total Centres | Private for Profit | Proportion for Profit (per cent) |

| September 2013 | 13,676 | 5,355 | 39.3 |

| June 2025 | 18,018 | 9,721 | 53.9 |

There has been a massive acceleration in the ‘Private for Profit’ management type.

If you do the sums, you will realise that from when the first data was published under the NQF (September-quarter 2013) to the most recent data (June-quarter 2025), the total number of childcare centres has risen by 4,342 (or 31.7 per cent).

Under some circumstances such a growth rate would be celebrated because it would mean more children (in absolute and proportion of total population) are being cared for while their parents (principally mothers) are able to work at least some hours.

But then you also realise that the change in the number of ‘Private for Profit’ centres was 4,366 over the same period (81 per cent) and as a proportion of the total change 100.6 per cent.

In other words, all the growth in child care has been in the ‘Private for Profit’ area and then some.

Which means more children are being pushed into centres, which have the aim of making as much profit as they can at the forefront.

Which is one of the major reasons for the massive failures that are now coming to light, almost on a daily basis.

The National Quality Standards under the NQF “includes seven quality areas that are important to outcomes for children” (Source):

QA1 Educational program and practice

QA2 Children’s health and safety

QA3 Physical environment

QA4 Staffing arrangements

QA5 Relationships with children

QA6 Collaborative partnerships with families and communities

QA7 Governance and leadership

Centres are rated under each QA into five different categories:

– Excellent rating, awarded by ACECQA

– Exceeding National Quality Standard

– Meeting National Quality Standard

– Working Towards National Quality Standard

– Significant Improvement Required

An overall NQS rating is then given.

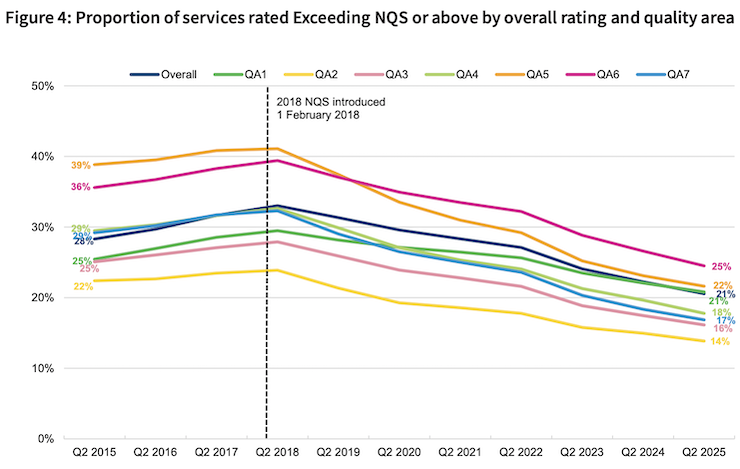

The following graph is taken from the latest NQF Snapshot linked to above (Figure 4) and is self-explanatory.

As the proliferation of ‘Private for Profit’ centres has occurred the proportion of services ‘Exceeding NQS’ has fallen dramatically.

Note the QA2 result, which relates to ‘Children’s health and safety’ – terrible outcome.

Only 11 per cent of the ‘Private for Profit’ centres exceed the NQS as at the June-quarter 2025 (overall average across all management types is 20 per cent).

At the failure end, which the regulators euphemistically categorises as ‘Working Towards NQS’, 10 per cent of the ‘Private for Profit’ centres are classified.

That is, around 970 ‘Private for profit’ centres are not currently meeting the national minimum quality standards.

The outcomes for the ‘Not for profit’ centres are much better.

Why the disparity?

On January 29, 2024, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, statutory body of the Federal government which regulates competition in Australia, released its final report of the – Childcare inquiry 2023.

Unsurprisingly, it found:

1. “In particular, childcare markets under current regulatory settings are not delivering on the key objectives of accessibility and affordability”.

2. “educator labour force shortages are affecting all childcare markets, in terms of both the supply of childcare services and the costs to supply these services” – workers are not attracted to the sector because the ‘Private for profit’ centres have set up low-paid, overworked conditions with repressive management approaches.

The Inquiry found that:

Factors that appear to be contributing to workforce shortages and educator burnout include:

– less attractive pay and conditions than in other similar industries such as primary school teaching

– increasing responsibilities and burdens on educators

– the common need for staff to allocate unpaid personal time to study for required qualifications (also affected by current cost of living pressures)

– the ongoing impacts of COVID-19 (which has reduced the supply of workers from overseas).

The ‘Private for profit’ centres has higher casual staff ratios than the not-for profit centres and also take on more junior staff to cut costs.

Their aim is to pay as little as they can for labour.

The results are obvious – the standard of care is lower and there is a higher staff turnover.

3. “Childcare fees across all services have grown faster than inflation and wages since the introduction of the Child Care Subsidy” – see also point 5 – profit-gouging is relentless.

The Inquiry found that:

In the September quarter 2023, about 41% of large for-profit centre bases day care services charged an average hourly fee over the hourly rate cap, compared to 15% of large not-for-profit services.

4. “Not-for-profit providers appear to face lower land costs than for-profit providers, but these savings are invested into labour for centre based day care services.”

5. “On average, margins are higher … for for-profit providers of centre based day care than not-for-profit”.

6. “Not all markets are adequately served” – the ‘Private for profit’ will not go into regional and remote areas or where the margins cannot be inflated.

The Inquiry found that:

The significant growth of for-profit providers and their presence in Major Cities and more profitable areas may go some way to explaining the existence of under-served.

It is now well-documented that the push to allow the profit motive to dominate decision making in the child care sector has led to massive failures.

We have shifted from a model (defined in the 1972 Act) of a service that would prioritise the provision of high-quality care through the agency of highly qualified staff to a still highly-subsidised sector dominated by corporations who seek to cut costs to the bone in order to record high profit margins.

The cost cutting extends to staffing, the food provided to the children under care, the standard of the physical infrastructure, the cleanliness of the centres and the rest of it.

This 2009 research article by two leading academics in the area – Child Care in Australia: A market failure and spectacular public policy disaster – is sobering reading.

They open with:

Australia, once regarded by international observers as having an enviable child care system, has become a case study for other countries in what not to do,

In March 2025, the Australian Broadcasting Commission’s investigative program Four Corners ran a special show on the sector.

This ABC news article (March 18, 2025) – Tens of thousands of children attend childcare centres that fail national standards – summarises the key aspects of the Four Corners program.

It is not happy reading.

The investigation revealed a staggering failure of the ‘Private for profit’ sector and the regulative framework that has allowed the failure to grow over time as profit is put before care.

Children are regularly injured and ignored.

They are tied to chairs with straps

Underqualified staff are forced to work in a “culture of coercion”

The managers keep an array of toys and materials that they hide on a day-to-day basis but bring out when the regulators visit to assess the quality of care.

Privatised higher educational colleges (that is another problem) issue fake qualifications to childcare workers for cash.

Further, the government which is obsessed with achieving fiscal surpluses typically under funds the regulative agency it created.

The regulator allows centres that fail to meet the NQF standards to continue while classifying them and moving towards the standard.

The most recent revelations that the child safety assessment framework is ‘porous’ is demonstrating that the failures of the system are also allow child sex predators to get key jobs in childcare centres to commit crime on a daily basis.

Conclusion

The childcare sector is only one of the many that have been subjected to private profit principles and which have categorically failed in their charter.

We now have a system in Australia that systematically damages our children while the providers reap massive profits generated via government subsidies.

The answer is simple – drive the ‘Private for profit’ providers out – defund them.

But no government has shown the courage to do that despite the failures becoming more obvious each day and the consequences more than any healthy society can bear.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2025 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.