MCD

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

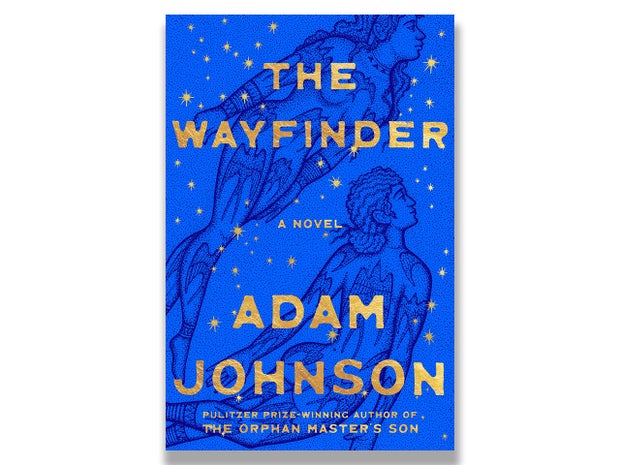

Adam Johnson won a Pulitzer Prize for his novel, “The Orphan Master’s Son,” and the National Book Award for his collection of short stories, “Fortune Smiles.” He returns with an epic tale set in Polynesia a thousand years in the past.

In “The Wayfinder” (MCD), a bold young woman and two sons of a king journey through storms, myths, and an empire on the brink of chaos.

Read an excerpt below.

“The Wayfinder” by Adam Johnson

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

KŌRERO:

THE PAST IS THE FUTURE

I’d opened my share of graves before finding something of value: a pendant in the shape of a fishhook, carved from greenstone. Greenstone only came from Aotearoa, the land our people had fled before we ended up on this island. The pendant, when held to the sun, glowed soft and green as dawn through miro trees. I was of the third generation born on this island, but the pendant was from our ancestors, from before. My father said a fishhook necklace had a special meaning: it ensured seafarers safe passage over water. To wear the pendant, I braided a cord from the inner bark of a hibiscus branch, which produced a fiber so strong, even parrots couldn’t bite through it.

Unpleasant as it was, and offensive to our ancestors, I was ready to open more graves.

Still, I had other duties to perform. I was up each morning before dawn to hunt birds. Pigeons in planting season, tūī birds when the flax blossomed. This time of year, it was parrots. They arrived on our island in closely bonded flocks, and it was these social connections we’d exploit to ensnare them. When our ancestors landed on this island, it was so full of birds, they named it Manumotu, or Bird Island. If only that were still the case. These days, we’d quietly crouch all morning, ready to trigger our snares, in the hopes of catching a bird or two. The worst part was the silence. I’m the talkative type. My mother says I was born speaking, which is why she named me Kōrero. Only after hours of silent birding was I free to open graves with my best friend Hine. The two of us could talk all day.

Hine’s duties, unlike mine, were endless. She’d been but a girl when her mother died and she was given to an older, childless woman named Tiri. But after a few years, when Tiri went blind, it was Hine who became the caretaker. Tiri was one of the most amazing persons in the world — I admit I only knew eighty-four people — but Hine, like me, was sixteen years old, and nobody likes it when they have to do something. And Hine had to do everything for Tiri.

After birding on the morning this story begins, I arrived at our island’s cove to continue digging. Many people trapped on this island before us were buried around the cove. This was considered a good resting place because of the view and the breeze and because this was where birds landed after open-water voyages. Where’d the birds come from? I always wondered. Where’d they fly off to?

I tethered my parrots to a branch. One was named Aroha — it was she who lured the wild parrots into our traps. I’d tug on Aroha’s tether, she’d squawk in distress, and wild parrots would come to her aid.

“I ohiti rā,” I said to Aroha. “I ohiti pō.”

This was a fisherman’s adage, shortened to fit a bird’s memory. Alert by day, the saying went. Alert by night. My father was a fisherman.

I knew from old stories that parrots could be made to talk, though I’d had no luck at it.

The other parrot was freshly caught. We’d named her Kanokano — the complications she caused are soon to be described.

With only a digging stick and a basket, I picked a likely spot on the upper beach and began moving sand. If only our ancestors had thought to mark their graves. But I suppose they didn’t imagine being exhumed by their great-granddaughters. I ran into a lot of mangrove roots, which I hacked with the jagged edge of a mussel shell. By the time Hine and Tiri arrived, I was sweating.

“What’s the ocean like today?” Tiri asked. Her pearled-over gaze was directed at nothing.

Hine rolled her eyes and helped the old woman onto a mat before handing her her weaving.

“It’s blue, it’s wet,” Hine said impatiently. “The waves go up and down.” I described for Tiri how late-morning light penetrated the cove, illuminating the humps of mullet, how the distant reef-break frothed like coconut pulp, how sputtering waves reached up the beach before fingering all the little shells in retreat.

Hine half-heartedly stabbed at some sand with her stick.

I asked, “Did you hear the Toki brothers found an earring in a grave?” I was arm-deep in the hole, fighting roots.

“The Toki brothers are insufferable,” Hine said. She made a gesture to help me, but looking in the hole saw I was already to the point where smelly water was seeping in.

“The earring was greenstone,” I said. “From the old world. I bet one of the brothers brings it to you. Will it be the big, handsome, doltish one? Or the big, handsome, inane one?”

“Don’t make fun of me,” Hine said. “You’ll have to marry the one I reject. And have his baby.”

The Toki brothers were slow-witted, trusting, and humorless. But their father was charismatic and funny, and the truth was, Hine had a parent-crush on him. It was quite possible that when the marriage ban was lifted, she’d marry a Toki brother just to become the daughter of Papa Toki.

Tiri took a breath. She always did that before beginning a story. While Hine had no patience for the old tales, I could hear them all day. Today was the story of Paikea, who was one of the navigators who discovered Aotearoa. He was from a place called Hawaiki. Tiri didn’t start in the obvious places, like Paikea’s departure from Hawaiki or his arrival at Aotearoa. She didn’t start with Paikea sinking a canoe and drowning his seventy enemies. Nor with him being saved by a whale. Instead, she started that epic tale with a little moment: Paikea, succumbing both to vanity and shame, as he groomed his hair with a forbidden comb.

All the while, Tiri did her weaving — her fingers displaying their own kind of sight.

My hole reached the point where sand fell in as fast as I scooped it out. Hine scrunched her nose. It’s probably clear that Hine’s heart really wasn’t into digging up graves. She could barely bring herself to touch any bones, and when she did, she was afraid they might belong to her mother, even though we knew her mother was buried up the hill, above the kūmara fields. We’d both been there when she was put in the ground. Still, one person’s bones can look like another’s, which can look like anybody’s, which might as well be your mother’s. I hoped Hine would change her outlook when she finally found something of value in a grave.

That’s when my digging stick made the unmistakable knock of wood striking bone.

Tiri paused her story. I reached into the dark water and felt something in the muck. Hine winced, afraid of what I’d pull out. “I’m sorry, ancestor,” I said. Then, with a sucking sound, I tugged out a dog skull. I reached back for its jaw, but the mud offered only bird bones and broken shells.

“Another junk pit,” Hine said, and started pushing sand back into the hole.

I contemplated the skull. Since we’d begun digging up the dead, I’d come across many dog remains. Did they happen to die at the same time as our ancestors? Were they slain and buried alongside? Or was it something else altogether? No living person on the island had ever seen a dog, and before we started digging, it was thought that dogs had never even been here.

“What is it?” Tiri asked.

“Another dog skull,” Hine said. “Look at those teeth. Who’d want to get close to one of those things, let alone share the afterlife with it?”

“Dogs had white fur, soft as tūī feathers,” Tiri said. “The old stories say they’d lick your face.”

“They supposedly had long tongues,” I said, marveling at the skull. Hine shook her head. “You don’t believe every story you hear, do you?” Hine knew that I did, indeed, believe every story I heard.

“There’s only one thing we know for sure about dogs,” Hine said. “They must’ve tasted good.”

What interested me was the size of a dog’s eye sockets. Kākā parrots also had large eyes. In fact, the eyes of a parrot were quite intelligent and expressive. “Ancestors are supposed to be wise,” I said. “But they didn’t leave us a single dog.”

Hine eyed its fangs. “I’m glad they’re gone.”

“Parrots have sharp beaks,” I said. “And they’re friendly.” Hine took the skull and threw it.

“One of these days, you’ll lose a finger to those birds,” she said.

Already, I’ve forgotten some stuff. That’s how bad a storyteller I am. I should’ve mentioned that I was absolutely forbidden from teaching my parrots human words, that Hine had a father who was alive and walking around our island — we just didn’t know his identity. That Papa Toki had lost an arm, with my mother and Tiri being the ones who cut it off.

But it’s too late, the story’s begun. Aroha looked toward the cove, spread her wings, and began screeching. We turned. Drifting in past the reef was the largest waka canoe imaginable. It had two hulls and rocked silently with the waves. Most canoes in the old stories were waka taua, war canoes. This one seemed empty — not a person or a paddle or a sail was visible. We beheld its pitched bows and soaring mast. Most ominously, the symbol of a death-bringing frigate bird was carved down its side. Then we heard it: upon the spar was a large parrot with a crimson body. It had spread its wings and was screeching back.

“What is it?” Tiri asked. “What’s going on?”

“We have visitors,” Hine said. She took my hand in hers, and then she screamed.

It seemed to me that, at the sound of Hine’s voice, dozens of warriors would sit up in the waka and reveal themselves. I took hold of my fishhook necklace because, like the waka before me, it felt both ancient and startlingly new.

Did I mention that in all our years on the island, we’d never had a visitor? As Hine’s scream echoed off the cliffs, the hum of island life stopped.

Silenced were the sounds of flax being beaten on the leeward shore and of our fathers excavating burial sites on the south-facing bluffs.

Our fathers — all the men of Bird Island — would be here in no time.

I should say the waka wasn’t a total surprise. We knew something was coming. There’d been signs.

From “The Wayfinder” by Adam Johnson. Copyright © 2025 by Adam Johnson. Reprinted with permission of MCD, an imprint of Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC.

Get the book here:

“The Wayfinder” by Adam Johnson

Buy locally from Bookshop.org

For more info:

- “The Wayfinder” by Adam Johnson (MCD), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats