Earlier this month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released preliminary benchmark revisions suggesting that job growth was only about half as fast as originally reported through much of 2024. To be clear, these revisions are not corrections of mistakes, but rather part of the regular, transparent process to update employment counts with the most comprehensive data available. In this case, the payroll employment numbers are benchmarked against unemployment insurance tax records, which represent about 97% of total employment.

It might be tempting to think that this preliminary downward revision means that the U.S. economy was much weaker than originally reported. But most of the slower job growth in 2024 was the result of smaller working-age population growth due to reduced immigration and the aging of the workforce—it was not due to degraded labor force participation or opportunities for prime-age workers in the U.S. labor market. In fact, research shows that there were about 600,000 to 900,000 fewer net immigrants between 2023 and 2024. Smaller population growth requires smaller increases in the number of jobs to maintain employment rates.

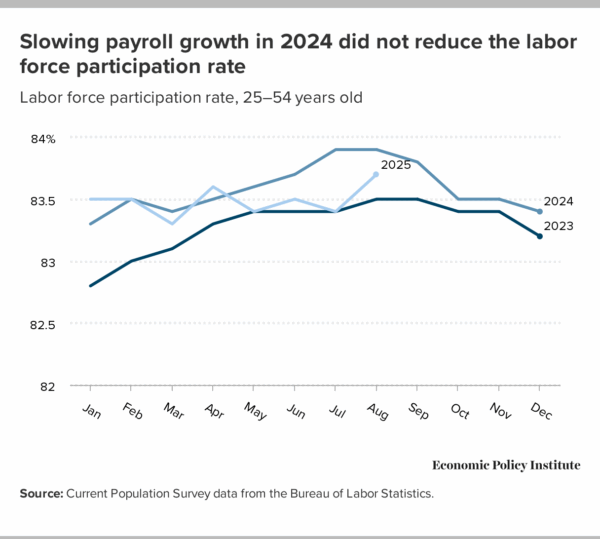

A clear way to see how the labor market stayed strong in 2024 in the face of lower job growth is to look at prime-age labor force participation, ages 25 through 54. This uses data from the Current Population Survey—which is unaffected by potential payroll revisions— and focusing on prime-age workers limits the role of the aging workforce from affecting recent trends in the data. If rates of labor force participation stay stable even as the number of jobs falls, then this implies that a reduction in labor supply has been well-absorbed by the labor market and has not translated into fewer job opportunities for the workers remaining in the U.S. economy.

Figure A shows that the prime-age labor force participation rate was higher in every month of 2024 compared with 2023. So even as payroll growth may have slowed, labor force participation grew in mid-2024 and stayed at least as high through the beginning of 2025.

Labor force participation has stayed relatively flat in 2025, and in general most labor market indicators have remained pretty solid in 2025 compared with the longer historic record. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio is still close to its pre-pandemic level. Unemployment did increase in 2024 and 2025 but the rate is still low by historical standards.

At the same time, some indicators suggest a labor market that is softening as 2025 moves on. There has been a marked decline in payroll employment growth—averaging only 29,000 jobs per month since May. Nominal wages are still rising faster than inflation, but the pace of private-sector real wage growth is half as fast as it was three months ago. Layoffs remain low and regular state unemployment insurance claims aren’t rising, but federal unemployment insurance claims are about twice as high as they were last year at this time.

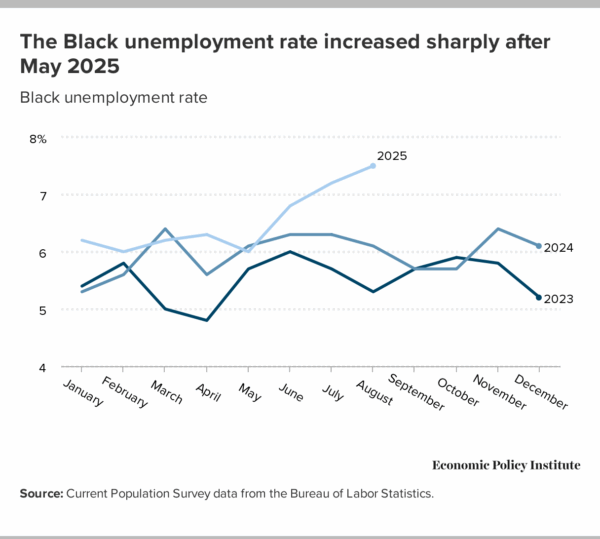

We also see troubling signs of weakness in the unemployment rates for specific demographic groups. For example, the labor market for Black workers has deteriorated in 2025. Figure B shows that Black unemployment held relatively steady in 2024, but over the last three months Black unemployment rose to 7.5%, its highest in nearly three years. The labor market experience of Black workers has often been considered a bellwether, as Black workers not only experience much worse outcomes in a downturn but also may experience that downturn first.

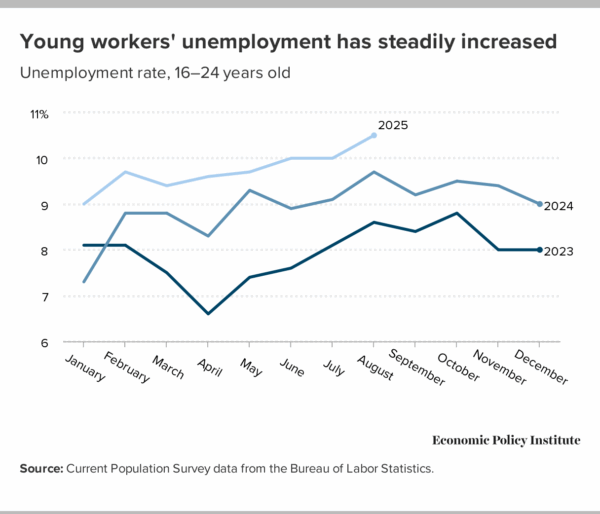

Another group seeing troubling trends are young workers, those ages 16 to 24 (shown in Figure C). Although the unemployment rate for workers above the age of 25 has stayed relatively flat over the last year, the unemployment rate for young workers has been steadily rising—hitting 10.5% in August, the highest it has been in 3.5 years. Higher unemployment among young workers is also consistent with a softer hires rate, making it harder for new entrants to break into the labor market.

Black and young workers’ labor market outcomes are more volatile because of smaller sample sizes, but the recent deterioration is hard to ignore. Because many rates in the household survey did not noticeably deteriorate in 2024, slower payroll growth in that year seemed to be driven simply by slower population growth. In 2025, however, there are now preliminary signals that job growth may be slowing enough to reflect deteriorating employment prospects for at least some groups of workers. If the latest jobs report is released on Friday (which may be delayed given the possibility of a government shutdown), we’ll track employment and unemployment rates from the household survey to see if the labor market is continuing to weaken.