Semiconductors are everywhere. They power your phone, your car, your refrigerator. They enable AI models, cloud computing, and modern manufacturing. Advanced chips control weapons systems, telecommunications networks, and financial infrastructure. No technology is more central to modern economic activity.

This makes competition in semiconductor manufacturing a question of enormous importance. Yet the industry presents a puzzle that challenges conventional thinking about competition and market power.

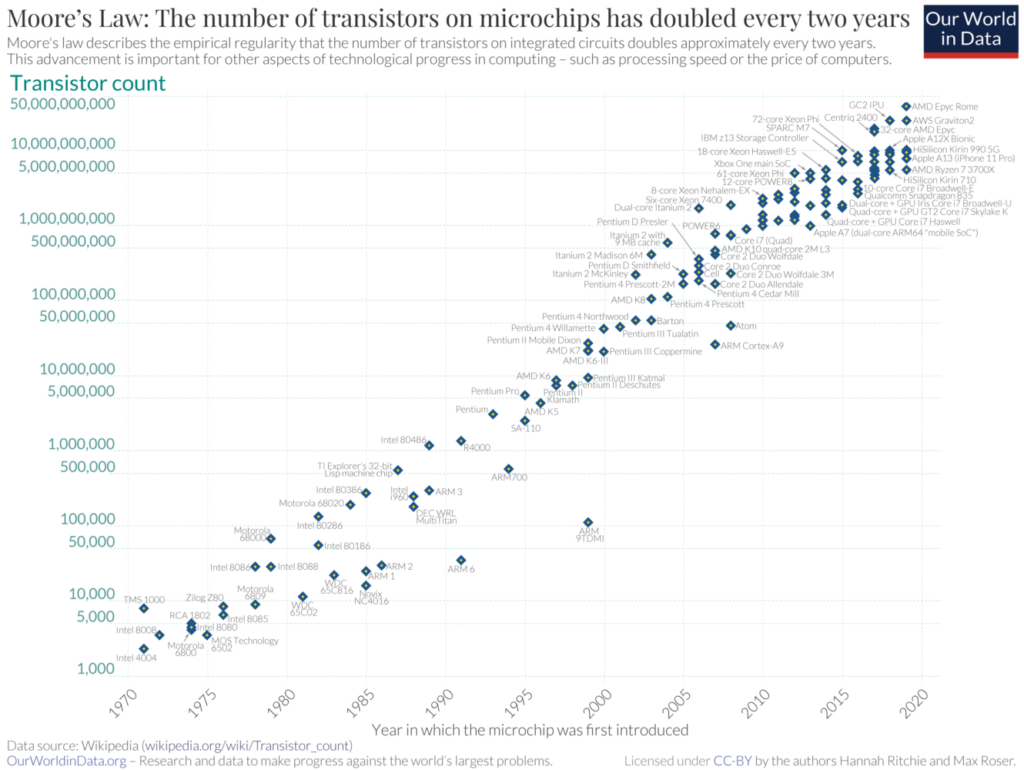

Moore’s Law, the observation (then prediction) that chip performance doubles roughly every two years, has held steady for five decades.

Meanwhile, the industry has consolidated dramatically. By 2020, dozens of chip manufacturers from the 1980s had evolved into three leading players, with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) now producing most of the world’s advanced processors.

By standard antitrust metrics, the semiconductor industry appears problematic. Market concentration has risen steadily. The largest firms command dominant market shares. Entry barriers appear massive: a new fabrication facility costs more than $20 billion. These metrics suggest competition is weak or weakening, creating the conditions for stagnation.

But that’s not what’s happened. Instead, innovation thrived as the industry consolidated, maintaining the pace predicted by Moore’s Law (meaning, generally, more computing power at lower prices) even as the industry concentrated into fewer hands.

The question is—how can an industry be both highly concentrated and intensely competitive? How can fewer firms produce constant innovation? And what should this teach us about using standard measures of competition, as well as the appropriate focus of antitrust enforcement?

These are the questions David Teece, Geoffrey Manne, Mario Zúñiga, and I explore in a new paper on competition in semiconductor manufacturing. In this post, I want to augment that analysis, using the framework developed by two of this year’s Nobel Prize winners, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt. Their model of Schumpeterian creative destruction, which I wrote about recently, explains why the chip-manufacturing industry simultaneously exhibits both constant, relentless competition and high concentration.

Smooth Growth from Turbulent Churn

Before getting to the specifics of semiconductors, start with the macroeconomic patterns. Advanced economies show smooth, steady GDP growth; in the United States, this has meant roughly 2% annual growth for decades. The semiconductor industry has maintained similarly smooth exponential productivity improvements through Moore’s Law for five decades.

Yet underneath that smoothness, individual markets experience dramatic upheaval. How do we get steady macro-level growth from such turbulent micro dynamics?

Semiconductors present a similar puzzle. Transistors got smaller, chips got faster, and it all happened at a remarkably steady pace. If one were to plot chip performance over the years, you would see a smooth, predictable curve.

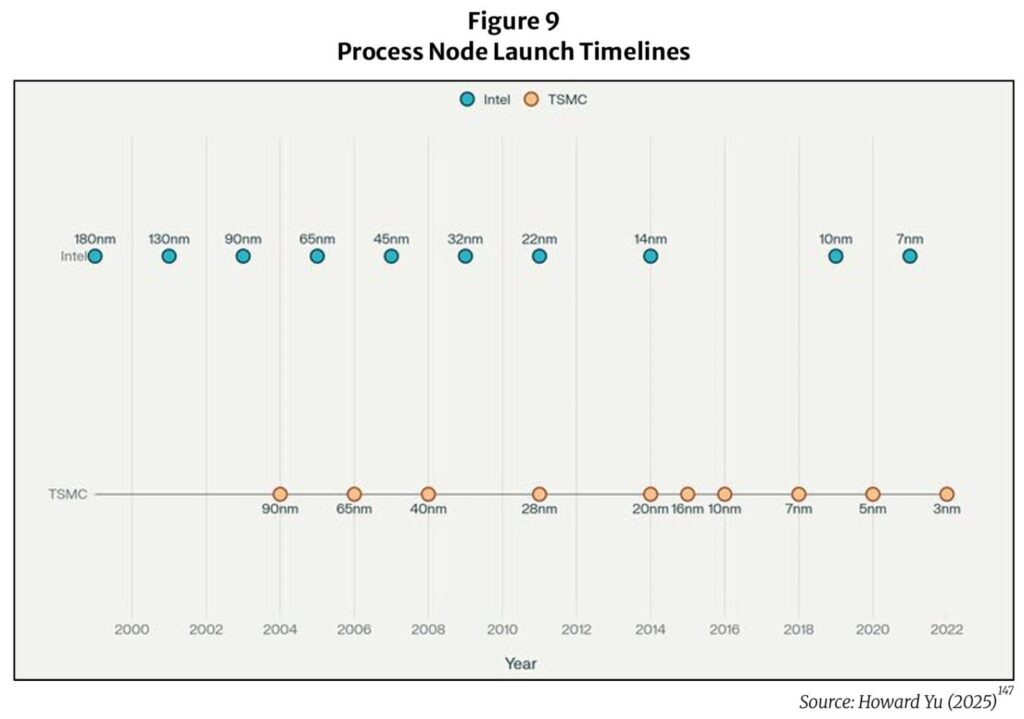

But in both the macroeconomy and the semiconductor industry, while the trend looks smooth, the firm-level picture is chaotic. In 2015, Intel led logic-chip manufacturing with its 14-nanometer process. Samsung and TSMC raced to catch up and, by 2017, they had matched Intel. Then TSMC pulled ahead with 7-nanometer in 2018. Intel stumbled on 10-nanometer for years. TSMC maintained its lead through 5-nanometer and 3-nanometer. Apple abandoned Intel processors entirely, switching to TSMC-manufactured chips. Intel’s market capitalization reflected this fall from grace.

This pattern of one firm innovating, others catching up, someone else pulling ahead, and yesterday’s leader falling behind repeats constantly. Netflix enters, and Blockbuster collapses. The iPhone launches and BlackBerry disappears. The semiconductor industry follows the same pattern of creative destruction: TSMC displaced Intel from the lead, and Intel is now investing billions to try to recapture its position.

Each transition reshuffles market leadership among firms. In semiconductors, each new process generation (about every two years) displaces the last, so it is a new opportunity for a new firm to take the lead. We have smooth aggregate growth built on creative destruction at the firm level. How does this actually work?

Serial Monopoly in Action

The Aghion-Howitt framework provides the answer: serial monopoly. Firms take turns being monopolists as each new leader displaces the last.

Success brings temporary monopoly profits. When TSMC got to 7-nanometer before Intel, it captured most of the market for advanced-logic chips. Those profits are substantial, with gross margins above 50% on leading-edge chip manufacturing.

These temporary monopoly profits are central to how innovation works in the semiconductor industry. Developing a new process node requires billions in upfront investment, with no guarantee of success. The possibility of capturing the market and earning substantial profits for a period of time is what justifies these massive bets. Without the prospect of temporarily high returns, no firm would make such risky investments. The monopoly profit is the carrot that motivates massive R&D investment.

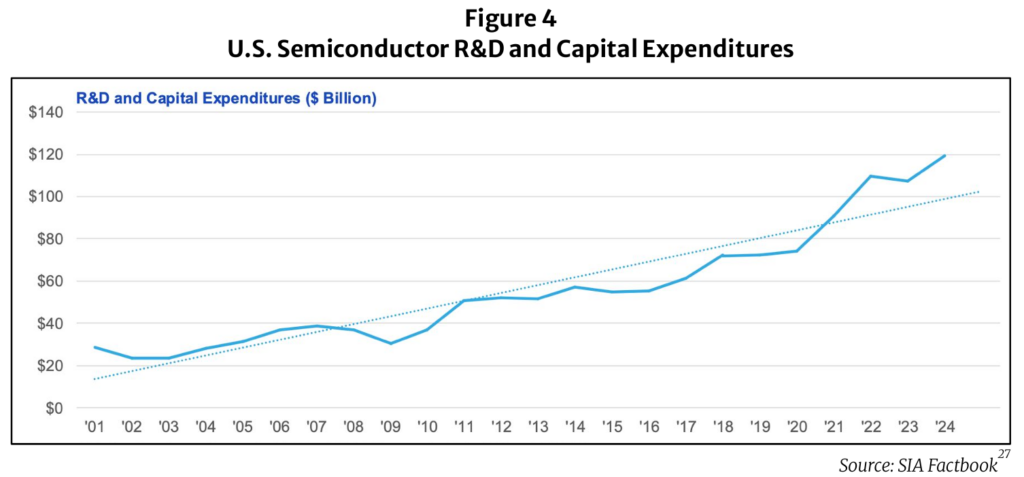

But the monopoly remains temporary because rivals keep investing to displace the current leader. Even the current leader must invest billions to maintain its position. Despite leading advanced manufacturing, TSMC spent $6.4 billion on R&D in 2024. It cannot rest on its current position because it faces the same pressure to innovate as its challengers, knowing that any stumble means displacement. Intel, trying to regain its technological edge, spent $16.5 billion (31% of its revenue) on R&D. Samsung invests similar amounts.

If we zoom out beyond manufacturing to consider the broader industry, with better data, the semiconductor sector as a whole is one of the most R&D-intensive industries in the world. In 2024, overall U.S. semiconductor-industry investment in R&D totaled $62.7 billion, representing 18% of U.S. semiconductor firms’ revenue.

This is competition working, but it looks nothing like the textbook model. Firms in this industry don’t compete primarily by cutting prices on identical products to capture a bit more market share. They compete by racing to develop better products that make existing ones obsolete, capturing the market entirely. That is, at least, until the next innovation comes along. The competition happens through innovation, not just price.

This pattern creates what economists call “competition for the market,” rather than “competition in the market.” But it is competition nonetheless. Each new process node requires billions in research spending. These investments fund thousands of engineers working on photolithography, materials science, and manufacturing processes. The firm that gets to the next node first captures most of the market for that generation. Every competitor aims to displace it at the next node. For its part, TSMC knows that a single missed transition could reverse years of leadership.

Why Standard Competition Metrics Fail

Our paper examines how dynamic competition operates, which helps to explain why traditional antitrust metrics miss what’s actually happening.

The old structure-conduct-performance paradigm in antitrust assumes that market structure determines competitive behavior and, ultimately, market performance. Under this view, concentrated markets with few firms should produce higher prices, lower output, and reduced innovation because firms face less competitive pressure. When regulators see three firms controlling advanced semiconductor manufacturing, the paradigm suggests these firms can coordinate behavior, raise prices, and avoid the costly investments that competition would otherwise force.

While economists abandoned the strong form of this paradigm decades ago, modern antitrust analysis still relies heavily on structural metrics: how many firms, what market shares, what concentration ratios. These metrics would assume that the semiconductor industry is problematic. Three firms controlling advanced manufacturing looks like an oligopoly that should be earning excessive profits and underinvesting in R&D.

But inferring weak competition and poor performance from this structure misreads the competitive dynamics, especially in semiconductor manufacturing. Indeed, the semiconductor-manufacturing industry’s consolidated structure emerged from competition, not in spite of it. Competition led to consolidation around a few highly capable firms. In fact, that’s a standard result across many industries: competition increases concentration.

This mechanism is consistent with the Aghion-Howitt framework. Developing advanced manufacturing processes requires massive fixed costs. While a new fabrication facility costs $20 billion or more, chips sell for around $50 to a few thousand dollars each, depending on their complexity. Only firms that can spread those costs across enormous production volumes can recoup the investment. And the efficient scale has grown over time as the technology required to keep pace with Moore’s Law has become increasingly difficult.

This creates natural pressure toward concentration. But concentration doesn’t eliminate competitive pressure. Where there is a whole market’s worth of profits at stake, competition is fierce, and the competitive pressure of displacement provides the discipline that keeps firms investing and innovating.

The Intel case illustrates this process. Intel dominated logic-chip manufacturing for decades, but leadership did not mean complacency. Intel invested heavily in its 10-nanometer process, spending billions on new fabrication facilities and engineering talent. The company’s problem was not lack of effort. Instead, Intel’s engineers encountered unexpected manufacturing difficulties with the new process. Yields remained low, meaning too few working chips per wafer to make production economical. Intel delayed commercial production repeatedly while trying to solve these problems.

Meanwhile, TSMC succeeded with its competing 7-nanometer process. TSMC’s engineers took different technical approaches that proved more manufacturable. When Apple needed chips for its new Mac computers, it chose TSMC’s superior process over Intel’s delayed one. AMD, which had previously used Intel-equivalent processes, switched to TSMC and gained market share with chips that outperformed Intel’s offerings.

The displacement happened through innovation, not price cuts. Customers didn’t switch because TSMC charged less (although that mattered too). They switched because TSMC’s more advanced manufacturing process enabled better chips: faster, more power-efficient, with more features per unit area. Intel’s stumble demonstrates that no firm’s position is secure. But TSMC faces the same pressure today. If TSMC fails to deliver on 2-nanometer or the generations beyond, Samsung or Intel will capture those customers.

This is Joseph Schumpeter’s “creative destruction” in action.

Market structure is endogenous. The remaining firms and sizes are the outcome of competitive processes, not the point from which competition starts. TSMC became a big player by out-innovating Intel in a specific technological transition.

As we point out in the paper, the regional history of the industry confirms this pattern. In the 1980s, U.S.-based firms dominated semiconductor manufacturing. Japanese manufacturers invested heavily in process technology and quality control. They achieved higher yields (more working chips per silicon wafer) than their American competitors. By the late 1980s, most American memory-chip firms had exited the market.

From the traditional structure-conduct-performance perspective, this looks like a competition failure. U.S. firms lost. The market is concentrated. But innovation accelerated. Japanese firms competed with one other to improve manufacturing processes. Then, Korean firms entered with even more aggressive investments. Samsung displaced Japanese leaders through superior manufacturing technology.

What This Means for Policy

The semiconductor industry illustrates why we need to think differently about competition in innovative industries. Standard antitrust metrics—concentration ratios, market shares, price-cost margins—can mislead enforcers about competitive conditions in industries characterized by rapid innovation and large fixed costs. These metrics assume that market structure determines competitive intensity. But in Schumpeterian industries, especially, intense competition produces concentrated structures as successful innovators capture the market, only to face displacement at the next technological transition.

When it comes to policy, antitrust authorities must understand this reality about market competition. They must ask whether the conditions for ongoing creative destruction remain intact:

- Do incumbent firms face credible threats from potential innovators?

- Are firms investing in next-generation technology?

- Can new entrants or existing rivals displace leaders who stop innovating?

- Does the market reward innovation with temporary profits that fund further investment?

For semiconductors, the answers suggest competition is working well, despite high concentration. Firms invest enormous sums in R&D. New process nodes arrive regularly. Leadership positions remain contestable. Intel’s stumbles show no firm’s leadership is permanent.

Enforcement actions that make sense in static markets will completely backfire in Schumpeterian ones. Breaking up a leading firm might destroy the scale economies needed for the massive investments that generate that innovation. Punishing profits will eliminate the incentive for risky R&D bets. The more productive approach examines whether specific practices impede the competition in innovation that disciplines incumbents, not whether a particular market structure looks too concentrated.

The semiconductor industry has maintained Moore’s Law for five decades while consolidating from dozens of manufacturers to three leading players. Concentration did not produce stagnation. Rather, it produced continuous technological progress and regular leadership transitions as firms displaced each other through innovation.