A recent post argued that housing affordability is not so bad as it might appear when home prices are adjusted for all relevant factors, such as size, quality, and household income growth. While houses have become more expensive in dollars, they are also significantly bigger and nicer, and the average household has significantly more income.

We acknowledge, however, that there is a housing affordability problem, particularly for working- and middle-class people in certain metro areas. Bankrate found that the household income needed to afford a median-priced American home rose by 50% just since 2020, to $117,000.

The economics of housing affordability is very straightforward. If prices have gone up, either demand has shifted right, supply has shifted left, or some combination of the two. While supply constraints are the major culprit in the affordability problem, we want to acknowledge that buyers are partly responsible for the market shifts that we’ve seen—it takes two to tango. Housing is a normal good with a long-run income elasticity of demand close to one, meaning housing demand rises in tandem with household income growth.

To bring prices down, we need builders to shift the housing supply curve “out and right” by a larger factor than buyers are shifting the demand curve. Builders know exactly what this would take: less restrictive zoning (especially for multifamily units), easier licensing and permitting processes, less stringent building codes and energy standards, freer markets in labor and materials, and perhaps a consumer acceptance of smaller, simpler homes.

With our combined experience in home building and economic analysis, we see three major factors driving housing unaffordability: zoning, building codes, and home sizes.

Almost all U.S. jurisdictions impose zoning regulations that limit, sometimes severely, the number of homes that can be built. In the pursuit of safety and energy efficiency, ever-more-stringent building codes require costlier construction methods and materials. America’s builders have moved away from smaller, more austere starter homes to big, gaudy “McMansions.”

Zoning Prevents Affordable Housing

Economists have long recognized that zoning restrictions are one of the largest factors holding back housing supply growth. Urban-planner-turned-anti-zoning-crusader Nolan Gray wrote the authoritative critique of zoning, Arbitrary Lines (excellently reviewed by David Henderson). Gray spells out exactly how zoning raises housing costs:

The most obvious way is by blocking new housing altogether, whether by prohibiting affordable housing or through explicit rules restraining densities. This results in less housing being built, resulting in the supply-demand mismatches we see in most US cities today. A subtler way that zoning drives up housing costs is by forcing the housing that is built to be of a higher quality than residents might otherwise require, through policies such as minimum lot sizes or minimum parking requirements. Beyond these written prohibitions and mandates, zoning often raises housing costs simply by adding an onerous and unpredictable layer of review to the permitting process. (p. 52–53)

There’s plenty of evidence supporting the theory that zoning plays a major part in limiting housing supply and raising home prices. Exhibit A is Houston, the most famous example of a non-zoned large city, which, consequently, is one of the most affordable large cities in the United States. No zoning means Houston can easily add houses, particularly in response to even small price increases. As Gray notes, “Houston builds housing at nearly three times the per capita rate of cities like New York City and San Jose… in 2019, Houston built roughly the same number of apartments as Los Angeles, despite the latter being nearly twice as large.” (p. 144) This larger supply elasticity in Houston allows the housing stock to grow in tandem with demand and accordingly keeps price increases in check. For big cities, Houston is tops in affordability as measured by the ratio of median home prices to median household incomes.

Building Codes Raise Costs

Continuing a family tradition begun by Grandpa Watts in 1948, we built several spec homes in 2005–2006, raking in cash until we were derailed by the emergence of the subprime mortgage crisis.

Joel started building again after an almost 10-year hiatus, while Tyler headed off into academic economics. Touring one of Joel’s builds after the restart, Tyler noticed that all exterior walls were now constructed with 2×6 lumber, instead of 2x4s as had been standard practice since the advent of stick framing. Joel indicated this was due to changes in the building code, primarily for the purpose of adding more exterior insulation and making homes more energy efficient. This code upgrade was just one of the more noticeable examples of a steady trend of ever-more-stringent requirements, usually aimed at marginal improvements in safety and energy efficiency.

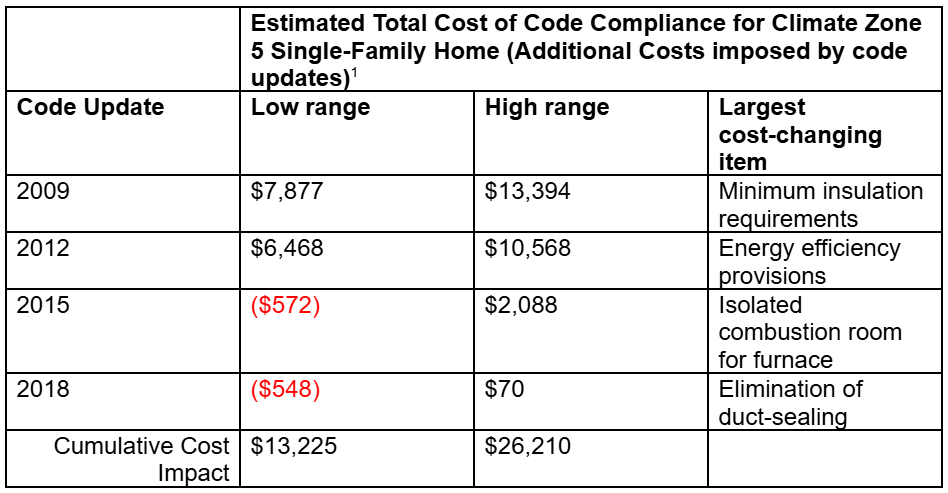

A series of studies commissioned by the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) tracked the total cost impact, on a per-home basis, of specific changes in the International Residential Code (IRC). These studies found that, over the 2009–2018 IRC update cycles, code changes increased costs for construction of typical homes in Joel’s area by an estimated $13,225 to $26,210. With ongoing updates, IRC has the potential to continue ratcheting up costs indefinitely.

Another study by NAHB found that government regulations overall (zoning, building code, design, safety, etc.) accounted for nearly 24% of the sales price of a single-family home—$93,870 when applied to the median new home price in 2021.

Small + Simple = Affordable

Homes in the United States have gotten a lot bigger since the supposed golden age of home affordability in the 1950s and 1960s. Average home size grew from 1,500 square feet in 1960 to a peak of 2,700 in the mid-2010s. Currently, new homes in the United States average about 2,400 square feet, and builders appear to have largely abandoned construction of small starter homes.

Homes under 1,400 square feet, once the majority, have collapsed to well under 10% of new home starts—despite the fact that the per-household head count shrank significantly since 1960.

;

Any push for more affordability should emphasize smaller and simpler houses—true starter homes. At the 2024 national average construction cost of $195 per square foot (including everything except land), today’s 2,400 square foot home costs over $200,000 more to build than a 1,200 square foot starter home would cost. Take out expensive amenities such as granite counters, premium appliances, high-end trim, etc., and we reckon site-built homes in the 1,200 square foot range, even in the priciest metros, could be built and sold profitably for a full $100,000 less than today’s national median price of about $410,000.

So why don’t we see more builders producing smaller, more basic homes to meet the crying need for affordable housing? Put simply, the large cost burden of regulations—zoning and building codes in particular—makes starter homes relatively unappealing for both buyers and builders.

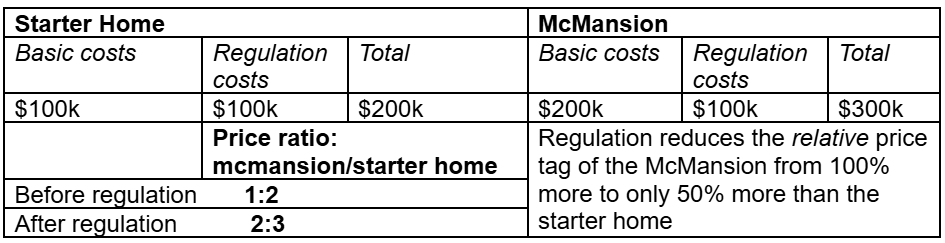

Allow us to illustrate by comparing the costs of a sample 1,200 square foot starter home against a high-end 2,400 square foot McMansion. We’ll assume the all-in costs of regulation add $100,000 per single-family home. Basic construction costs are, roughly speaking, directly proportional to home size and quality. Thus, in the absence of an extraneous regulatory cost burden, a 2,400 square foot home should run about double the cost-to-build of a 1,200 square foot home (land costs notwithstanding). The costs of a strict regulatory regime, however, are not proportionate to home size and amenities, but rather a roughly fixed amount for any size home. In other words, regulatory compliance adds almost the same amount of dollar outlay to the starter home as it does to the McMansion. The overall effect is to shrink the price gap between starter homes and McMansions, making the latter relatively less expensive compared to the former. Economists know this as the Alchian-Allen Effect.

In a less-regulated world, a starter home might be ½ the price of a McMansion, but once the regulatory burden is factored in, the starter home is instead 2/3 the price, and the larger the fixed cost of regulations, the smaller this relative price gap becomes. As the cost of regulations grows, the relative price of large, well-appointed houses declines. Unsurprisingly, builders and buyers increasingly eschew relatively more expensive starter homes.

Let there be “low quality” goods

The inimitable Walter Williams, our favorite econ teacher, used to say, “Low quality goods are part of the optimal stock of goods.” Of course—for how else could the material needs of poorer people be met? By this, Williams didn’t mean unsafe or non-functional, but rather made with cost in mind. In the case of homes, this would mean that they are smaller and simpler.

To ensure an abundance of lower-quality goods, governments must avoid burdensome taxes and regulations that make it unprofitable and unrealistic for entrepreneurs to operate in the low-end marketplace. Sadly, for many lower-income people looking for shelter, regulations have priced them out of the market.

To incentivize a reliable flow of affordable housing, we will need to see governments drastically peel back cost-prohibitive rules and restrictions imposed by zoning and/or building codes. “If you build it, they will come” rings true to us, but take our word for it: affordable homes won’t get built unless and until governments cut back this excessive regulatory cost burden.

Tyler Watts is a professor of economics at Ferris State University. His brother, Joel Watts, is a homebuilder.