Interchange fees charged by payment networks have in recent years been one of the most heated and persistent battles in financial regulation. These fees—typically 1-3% of credit-card transaction value in the United States—are charges that banks impose on merchants for processing credit- and debit-card transactions. What started as an obscure technical detail has exploded into a multi-billion-dollar policy dispute, involving massive litigation, regulatory intervention worldwide, and fierce debates among merchants, banks, payment networks, and policymakers.

The controversy centers on a fundamental conflict that arises within payment networks in their role as two-sided markets. Merchants argue that interchange fees are excessive and anticompetitive, forcing them to absorb significant costs or pass them on to consumers through higher prices. Banks counter that interchange fees fund essential infrastructure, fraud protection, and rewards programs that make electronic payments secure and attractive. This tension has sparked global regulatory responses, from the EU’s comprehensive fee caps to the Durbin amendment’s debit-card restrictions, to the proposed Credit Card Competition Act.

A recent working paper by Robert Hunt, Konstantinos Serfes, and Yin Zhang claims that capping interchange fees would benefit all consumers, even credit-card users whose rewards might decrease. Their conclusion contradicts substantial evidence from real-world implementations of interchange-fee caps. While mathematically elegant, the paper’s theoretical model relies on simplifying assumptions that obscure the complex realities of payment markets, and lead to policy recommendations that could harm the consumers they aim to help.

Understanding Interchange Fees

One of the major challenges that payment systems face is to persuade both merchants and consumers of their value. If too few merchants accept a particular form of payment, consumers will have little reason to hold it, and issuers will have little incentive to issue it. Likewise, if too few consumers hold a card, merchants will have little reason to accept it.

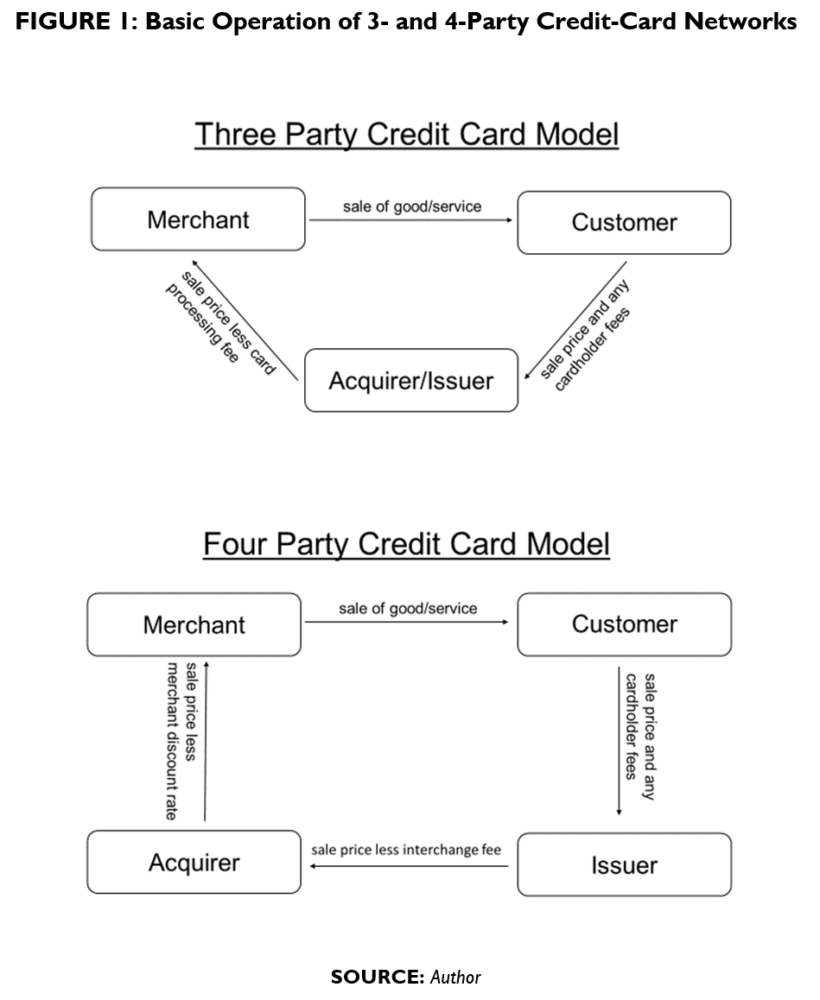

Transaction fees are the primary mechanism that credit-card-network operators use to balance the market. In three-party systems, such as American Express and Discover, the card-network operator acts as both issuer and acquirer, and charges merchants a card-processing fee (typically a percentage of the transaction amount) directly. In four-party systems, the issuer charges the acquirer an “interchange fee” (set by the networks) that is then incorporated into the fees those acquirers charge to merchants (called a “merchant-discount rate” in the United States). The figure below from an International Center for Law & Economics (ICLE) white paper illustrates how the two systems work.

The interchange fees charged on four-party cards vary by location, type of merchant, type and size of transaction, and type of card. An important factor determining the size of the interchange fee charged to a particular card is the extent of benefits associated with the card—and, in particular, any rewards that accrue to the cardholder.

The various three- and four-party payment networks have been engaged in a decades-long process of dynamic competition, in which each has sought—and continues to seek—to discover how to maximize value to their networks of merchants and consumers. This has involved considerable investment in innovative products, including more effective ways to encourage participation, as well as the identification and prevention of fraud and theft.

It has also involved experimentation with differing levels of transaction fees. The early three-party schemes charged a transaction fee of as much as 7%. Competition and innovation (including, especially, innovation in measures to reduce delinquency, fraud, and theft) drove those rates down. For U.S. credit cards, interchange fees range from about 1.4% to 3.5%, while the average is approximately 2.2%.

In general, economists have concluded that determining the “optimal” interchange fee is elusive and that the closest proxy is to be found through unforced market competition. They have therefore cautioned against intervention without sufficient evidence of a significant market failure.

How the Hunt, Serfes, & Zhang Model Undermines Two-Sided Market Theory

The Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang paper models interchange fees as a “credit-card tax” that increases retail prices for all consumers, whether they pay with cards or cash. They argue that capping these fees would reduce this tax burden, leading to lower retail prices that benefit everyone.

They acknowledge that credit-card rewards might decrease but claim the overall price reduction would be larger, creating net benefits for card users while helping cash users who currently subsidize card rewards through higher retail prices.

Credit-card networks represent the quintessential example of “two-sided markets”—platforms that must attract and balance the interests of two distinct user groups. In payment networks, success depends on getting both merchants and consumers to participate, creating value through network effects where each additional user on one side makes the platform more valuable to users on the other side. Merchants want more customers, and cardholders want to use their cards at more places.

The foundational insight of two-sided market theory is that platforms must carefully balance pricing on both sides to maximize value creation. As established by economists Jean-Charles Rochet, Jean Tirole, and Mark Armstrong, platforms face a fundamental tradeoff. They can extract revenue from one side only by making the platform attractive enough to maintain participation from both sides. This often requires subsidizing one side while charging higher fees to the other.

Credit-card networks exemplify this pattern—they provide rewards and fraud protection to attract cardholders, while providing benefits to merchants who need access to those customers, as noted in an ICLE issue brief:

Payment cards offer merchants multiple benefits, relative to cash: increased sales, faster throughput of customers, reduced fraud, and reduced theft from employees and third parties. Merchants that accept cards benefit from consumers’ ability to transact without having cash on-hand, increasing sales. Card payments are about twice as quick as cash, enabling merchants to serve more customers at lower labor cost, and to serve customers faster, thus benefiting other customers, who do not have to wait as long in line. Merchants can also maximize the value of sales and special pricing, as consumers can buy sale items without worry about having sufficient cash on hand or even sufficient short-term bank account liquidity to clear a check.

The Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang paper eliminates this core balancing feature of two-sided markets through its constant-elasticity-of-demand assumption. Elasticity measures consumer responsiveness to a change in price. For example, if demand elasticity is -0.5, then a 10% increase in price would result in a 5% decrease in the quantity demanded. Economic models often assume a constant elasticity of demand because it makes the arithmetic much easier.

But the real world is much more complex, even in our daily lives. Our elasticity of demand isn’t constant. If the price of ground beef increased by 10%, I might buy less meat and make my family smaller hamburgers. But if the price doubled, I might not buy any ground beef at all. (It’s mac and cheese week, kids!) My elasticity in response to a small price change may differ greatly from my response to a large price change.

The constant-elasticity-of-demand assumption is central to the Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang model; as they acknowledge, “consumers pay the entire burden of a tax or receive the entire benefit of a subsidy” with zero incidence on merchants. This means that in their model—unlike nearly every two-sided market—the platform faces no tradeoff between merchant and consumer pricing, because all cost changes pass through completely to consumers regardless of which side bears the initial cost.

This assumption transforms what should be a complex two-dimensional optimization problem into a simple one-dimensional analysis. In real two-sided markets, platforms must consider how price changes on one side affect participation and value creation on both sides. The constant-elasticity assumption makes merchant pricing strategically irrelevant to the platform’s optimization because merchants bear no cost, regardless of the fee level.

The result is that the Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang paper cannot analyze the distributional conflicts that make interchange-fee regulation economically interesting and politically controversial. By assuming away merchant incidence, the model eliminates the very tensions between merchant and consumer interests that drive policy debates about payment-system regulation.

More importantly, the authors’ assumption contradicts extensive empirical research showing that merchant pass-through rates range from 22% to 74%, with most studies finding rates near 50%. When the Durbin amendment capped debit interchange fees in 2011, studies found that 98% of retailers kept the savings rather than reducing prices. European research shows that consumers received only about 30% of interchange-fee reductions through lower prices.

The Monopoly-Network Assumption Ignores Competitive Dynamics

The Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang paper also assumes a single monopoly payment network. But in the real world, Visa and Mastercard together control a predominant share of payment processing in most developed countries. These networks compete vigorously for issuing banks who, in turn, compete for both merchants and cardholders through different fee structures, reward programs, and service offerings.

And while Visa and Mastercard dominate the U.S. market, American Express and Discover are viable and vital competitors. They may become even more so in the wake of Capital One’s acquisition of Discover. For example, a recent ICLE white paper concluded that:

Capital One’s acquisition of Discover’s payments network might result in more effective competition to Visa, Mastercard, and American Express, with broad benefits to merchants and consumers.

Network competition fundamentally changes pricing behavior in ways the monopoly model cannot capture. When multiple networks compete for cardholders, they increase rewards to attract users, which may lead to higher interchange fees that merchants must accept to avoid losing sales.

Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang’s monopoly-provider assumption also prevents their model from analyzing how regulation affects competitive balance between networks. In practice, capping fees on one network can shift transaction volume to unregulated alternatives, potentially increasing overall merchant costs, rather than reducing them.

Real-World Evidence Contradicts the Paper’s Predictions

The Durbin amendment provides the clearest test of what happens when regulators cap interchange fees. The regulation reduced debit-interchange fees by approximately 50%, creating annual savings of $6-7 billion for merchants. The Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang paper would predict that consumers should have benefited from lower retail prices and that the regulation should have improved overall welfare.

Instead, the opposite occurred. Banks subject to the regulation made substantial adjustments that harmed consumers, particularly those with lower incomes. Free checking accounts declined by 40 percentage points at large banks, from 60% to 20% of accounts. Monthly maintenance fees increased by $1.34 for basic accounts and $2.02 for interest-bearing accounts. Minimum balance requirements rose by more than $400 for basic accounts and nearly $1,700 for interest accounts.

These changes pushed many low-income consumers out of the banking system entirely. The regulation created a regressive transfer from households who rely on basic banking services to large retailers, who kept most of the interchange-fee savings as additional profit. Meanwhile, higher-income consumers largely avoided harm by maintaining higher account balances or shifting to unregulated credit cards with better rewards programs.

International Experience Confirms the Pattern

Australia’s experience with interchange-fee regulation provides further evidence against the paper’s optimistic predictions. After the Reserve Bank of Australia effectively reduced average interchange fees from about 0.95% to about 0.55%, rewards programs were substantially reduced, and annual fees increased.

The regulation failed to achieve meaningful price reductions for consumers, while creating new costs and inconveniences. Innovation in payment services slowed compared to markets without such restrictions, as reduced interchange revenue meant less investment in fraud protection, contactless technology, and other improvements.

European implementation of interchange-fee caps shows similar patterns. Despite regulatory requirements for merchants to pass through savings, studies consistently find that most benefits flowed to large retailers, rather than consumers. Small merchants often face higher overall costs due to compliance requirements and system upgrades needed to implement the regulations.

The Innovation and Investment Problem

The Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang paper does not address the relationship between interchange-fee regulation and innovation, investment, or service quality. While it’s unfair to criticize a theoretical model for not modeling something—especially something as complex as innovation, investment, or service quality—it must be noted that substantial evidence indicates that interchange revenue funds crucial payment-system improvements, including fraud protection, tokenization, instant card issuance, and contactless-payment technology. Each of these improvements directly benefits both consumers and merchants.

The paper’s focus on the so-called “credit-card tax” ignores important nonprice factors in payment networks. Countries that have implemented interchange-fee caps have experienced slower innovation in payment services compared to unrestricted markets. The reduced revenue from interchange fees has meant less investment in security measures that protect both merchants and consumers from fraud. Payment networks subject to fee caps also reduce investment in new technologies that could improve transaction efficiency and user experience.

Banks operate integrated business models where interchange revenue helps subsidize other services, including free checking accounts and low-fee credit products. When one revenue source is capped, banks must either replace it through other fees or reduce service quality.

Distributional Effects Favor Large Merchants Over Consumers

While the Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang paper claims that all consumers would benefit from interchange-fee caps, empirical evidence shows the opposite distributional pattern. Large merchants with sophisticated payment-processing operations capture most of the savings from reduced interchange fees. These merchants have market power with their customers and little incentive to pass through savings via lower prices.

Meanwhile, banks raise fees on deposit accounts, reduce rewards, and tighten lending standards to compensate for lost interchange revenue. These adjustments directly harm consumers, particularly those with smaller account balances who are least able to avoid new fees or meet higher requirements.

The result is a regressive transfer from ordinary consumers to large corporations. Research on the Durbin amendment has estimated that the prevailing effect is that low-income households effectively subsidize large retailers, with each cash-using household transferring approximately $149 annually to card-accepting merchants.

Implementation Costs and Market Disruption

The Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang paper treats interchange-fee caps as costless to implement and enforce, ignoring substantial compliance burdens that fall primarily on smaller merchants. Real-world implementation requires complex routing rules, terminal upgrades, dispute-resolution mechanisms, and ongoing regulatory oversight.

These costs can exceed interchange-fee savings for smaller merchants, making the regulation counterproductive for its intended beneficiaries. State-level proposals to cap interchange fees have demonstrated these implementation challenges, with merchants required to invest in new point-of-sale systems, train staff on routing requirements, and manage relationships with multiple payment processors.

This regulatory complexity may also generate various unintended consequences. When fees are capped on one payment method, consumers may shift to unregulated alternatives that impose higher merchant costs. The Durbin amendment led to increased use of credit cards, which carry higher interchange fees than the debit cards that were subject to the cap.

Policy Implications for Regulators

The Hunt, Serfes, and Zhang paper reaches conclusions that contradict extensive empirical evidence from actual interchange-fee regulations. Policymakers considering such caps should examine real-world outcomes, rather than rely on theoretical models with unrealistic assumptions.

The evidence consistently shows that interchange-fee caps benefit large merchants at the expense of consumers, particularly those with lower incomes who rely on basic banking services. These regulations typically fail to achieve their stated goals of reducing consumer prices, while creating harmful unintended consequences for financial inclusion and payment-system innovation.

Two-sided markets are complex and difficult to model, let alone to evaluate empirically. Policymakers should be skeptical of a model that essentially assumes away one side of the two-sided market (i.e., merchants) by treating it as a passive participant with no strategic role.

Future policy analysis should incorporate realistic assumptions about merchants’ pricing behavior, network competition, and bank responses to revenue losses. Only by understanding these complex market dynamics can regulators avoid repeating the mistakes of previous interchange-fee regulations that promised consumer benefits but delivered the opposite results.

The payment system serves essential functions in the modern economy, facilitating trillions of dollars in transactions while providing fraud protection, convenience, and financial inclusion. Regulatory interventions in this complex ecosystem require careful empirical analysis, rather than theoretical models that assume away the very market dynamics that determine real-world outcomes.