I’d like to begin with a tip of the hat to my former Federal Trade Commission (FTC) colleague Tara Koslov, who recently announced her retirement from the FTC after more than 28 years of service. Tara and I agreed on much, but far from everything. Heck, I have it on good authority that she hated my blog posts. But she was an excellent public servant whose contributions to antitrust enforcement, policy work, and the Bar were widely—and rightly—appreciated. I found her to be a smart and thoughtful antitrust lawyer who was also a smart and thoughtful manager—not the most common combination in the field. And her institutional knowledge was second to none.

Many good people have left the building over the past five years. It happens, but it adds up. There are more to follow, no doubt

Sticking with the topic of how it all adds up, Politico Pro reports that a:

House Appropriations subcommittee advanced legislation Monday that would slash $37 million from the Federal Trade Commission’s budget for fiscal 2026, while barring the agency from working with the European Union, United Kingdom and China on potential merger enforcement.

I’ve been a not-infrequent critic of my old agency, but that should not obscure the fact that there’s still important work for the agency to do, and there remain people in the building (buildings, plural, really) who are well and capable of doing that work. It’s not a huge agency. This does not help it.

Not What Anyone Ever Meant by the ‘Revolving Door’

U.S. District Court Judge Loren L. AliKhan ruled last week in favor of once-and-possibly-future FTC Commissioner Rebecca K. Slaughter in her suit challenging her (putative) dismissal from the commission (Slaughter v. Trump). Granting Slaughter’s motion for summary judgement, AliKhan ordered her reinstatement. The administration appealed and, by Monday afternoon, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit issued an order that temporarily stays the order that AliKhan had issued some four days prior, pending appeal.

As of 11 a.m. on July 22, Slaughter was still on the page of sitting commissioners on the FTC website. When I checked back at 3:30 p.m., she was not.

Where is this going? Well, nowhere immediately: the matter of the appeal stays with the D.C. Circuit Court. Eventually, and perhaps in the not-distant future, I expect that the case will work its way to the Supreme Court.

How did we get here? There’s a lot that might be read into that question, but to keep things relatively simple, I’ll point to my March 31 post. I won’t recapitulate that post here (not least because I just linked to it) but for the CliffsNotes version, I’ll briefly revisit a couple of points.

First, it’s not really surprising that a district court ruled in Slaughter’s favor: the plain language of Section 1 of the FTC Act stipulates for-cause (that is, not at-will) removal:

Any Commissioner may be removed by the President for inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.

And, of course, there’s the Supreme Court’s 1935 decision in Humphrey’s Executor, in which the Court upheld the constitutionality of the for-cause removal provision in the FTC Act.

Simple, no? Well, not so simple, as I—and many others—have pointed out. Several of the Court’s decisions—not least the 2020 decision in Seila Law—narrow the holding of Humphrey’s Executor. And there’s the fact that Chief Justice Roberts, writing for the Court in that matter, included a footnote addressing Humphrey’s:

The Court’s conclusion that the FTC did not exercise executive power has not withstood the test of time. As we observed in Morrison v. Olson, 487 U. S. 654 (1988), “[I]t is hard to dispute that the powers of the FTC at the time of Humphrey’s Executor would at the present time be considered ‘executive,’ at least to some degree.” Id., at 690, n. 28. See also Arlington v. FCC, 569 U. S. 290, 305, n. 4 (2013) (even though the activities of administrative agencies “take ‘legislative’ and ‘judicial’ forms,” “they are exercises of indeed, under our constitutional structure they must be exercises of—the ‘executive Power’” (quoting Art. II, §1, cl. 1)).

Slaughter’s attorneys can argue that the footnote is merely dicta, as the Court distinguished the CFPB (the agency at-issue in Seila Law) in ways that could be relevant to what it intends to do with Humphrey’s Executor. On the other hand, it’s hard to imagine a clearer signal of the direction in which this is headed, not least because at least three other justices now sitting on the court have said that they would overrule Humphrey’s Executor outright.

And yeah, 1+3 = 4, which is not five or six. I’m aware. But it seems to me that the writing is on the wall in big letters. Quoting myself again (tiresome, I know, but it seems efficient):

Whether a majority of today’s Court would overrule Humphrey’s Executor outright is unclear, but it might. In any case, it seems dubious that the Court would uphold the opinion’s application to the FTC of 2025. And, for what it’s worth, the DOJ has announced that it does not intend to defend Humphrey’s Executor in court.

I think that the Roberts footnote was right, which is not to say that it necessarily charts the best outcome from a policy perspective. As I wrote in March:

Personally, I think that Termination Tuesday was, on balance, a shame; that is, it seems to me unfortunate as a matter of practice, if not as a matter of political or constitutional principle. And for the most part (at least for a long time), the odd statutory structure of the FTC seemed to work in practice. Indeed, it seemed to work pretty well.

Slaughter says she intends to continue the fight. Posting on X.com, she writes:

I’ll continue to fight my illegal firing and see this case through, because part of why Congress created independent agencies is to ensure transparency and accountability. They didn’t want regulators doing shady, backroom deals without the people finding out, and I’m ready to uncover the ways the FTC is failing consumers and its duty to protect competition.

Well, maybe, although I don’t know of any such “shady, backroom deals.” And without wanting (or even being willing to) proclaim the current commission apolitical—indeed, without suggesting that politics was ever a complete non-issue at the commission level—it seems to me that the extreme tilt toward politicization occurred under the prior administration and, specifically, under the leadership of former Chair Lina M. Khan.

On transparency? I cannot help but recall the commission’s redaction—actual censorship—of then-Commissioner Christine Wilson’s dissent in the Meta/Within matter. And there was the much-reported gag order (see this staff report from the House Committee on Oversight and Accountability; or Politico if you prefer). I learned about this when supervisors confirmed that I had to withdraw from a very good panel discussion with barely two hours’ notice—a lunchtime web panel, and part of a good conference, by the way—with a suggestion that I mention the necessity of pressing work conflicts that were not themselves identified.

I can also think of two staff reports coming out of the Office of Policy Planning that were abruptly canned. We were instructed not to share the (rather advanced) drafts with anyone inside or outside the building any further, although they’d made the rounds with some in the Bureau of Economics and Bureau of Competition who’d already provided feedback on earlier drafts. We were told, specifically, not to share them with sitting FTC commissioners, such as Christine Wilson and Noah Phillips. These were reports where the work was begun under previous Chairman Joe Simons, but drafts were completed under Biden-era leadership, with the blessing (in one case, the direct and rather pressing instruction) of the new chair.

Of course, we staff were not free agents, and it’s within the authority of the commission itself to decline to publish FTC staff and FTC reports. Such documents don’t get the agency imprimatur without a vote, and the staff are not empowered to move for a vote. We could ask, sure, but that was as far as that went.

But censorship inside the building? With sitting commissioners asking to see the work, which they’d been told was forthcoming? I had never heard of such a thing in my 16 years at the agency and it seemed, at any rate, a departure from the plain language meaning of “transparency.”

This One’s a Gas

Some of my recent “agency roundup” pieces here at Truth on the Market have been focused relatively narrowly on a given issue or case, and maybe straining use of the term “roundup.” But let’s start with something that seems to me the right decision: In a 3-0 July 17 vote, the FTC reopened and set aside its January 2025 consent order in the Chevron/Hess matter.

The FTC had in September 2024 announced a consent order in the Chevron/Hess merger matter. While the initial complaint was voted out by a unanimous (and bipartisan) commission, the same could not be said of the September proposed order, or the final order approved in the waning days of the Biden administration in January 2025 by a 3-2 vote, over strong dissents by Commissioners Melissa Holyoak and Andrew Ferguson. For some telling excerpts, here’s Holyoak:

For the second time in five months, the Majority has used its leverage in the HSR process to extract a consent from merging parties with no reason to believe the law has been violated. To make it worse, once again, the consent targets an individual and deprives him of his contractual rights. I dissent.

And here’s Ferguson:

The Commission today authorizes the filing of an administrative complaint and proposed decision and order against Chevron Corporation and Hess Corporation. The Complaint alleges that Chevron’s proposed $53 billion acquisition of Hess Corporation would violate Section 7 of the Clayton Act.

The Complaint does not plead a traditional Section 7 theory because the Commission has none. Chevron and Hess together have a two percent share of the relevant market. No court has ever blocked a merger between companies with such small shares. The aggressive new Merger Guidelines presume that a merger would harm competition when it combines companies with market shares of over thirty percent. A two percent market share does not raise any competitive concerns at all.

They weren’t wrong. Whatever concerns might have given rise to the complaint, and whatever else might have been revealed in a full investigation and trial, had there been one, it seems clear enough that neither the complaint nor the order adequately state an antitrust claim against the merger. And the order’s insistence that “Chevron shall not, directly or indirectly, A. nominate, designate, or appoint John Hess to the Chevron Board; or B. allow John Hess to serve in an advisory or consulting capacity to, as a representative of, Chevron or the Chevron Board,” seemed gratuitous at best.

Rounding Up Other People’s Roundups

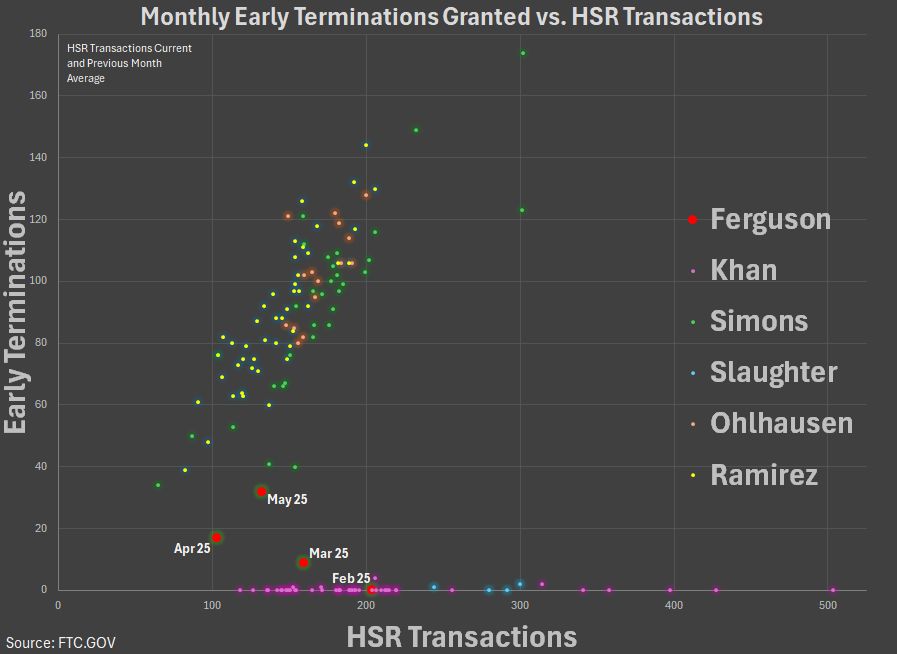

Let’s start with something quick and easy, but nonetheless interesting: My former FTC colleague Jay Ezrielev has posted some interesting graphics on Linkedin. One shows a recent rise in early-termination grants issued by the FTC.

When warranted, these are extremely useful. They help the agency to focus on proposed mergers that might reasonably raise significant competition concerns, and avoid wasting resources on those that don’t. They also minimize the drag on procompetitive mergers. As Ezrielev observes, these were “up in May and April but still significantly below pre-2021 levels.” And as he asks: “Is this the new normal or a slow transition to the old levels?” It’s worth watching.

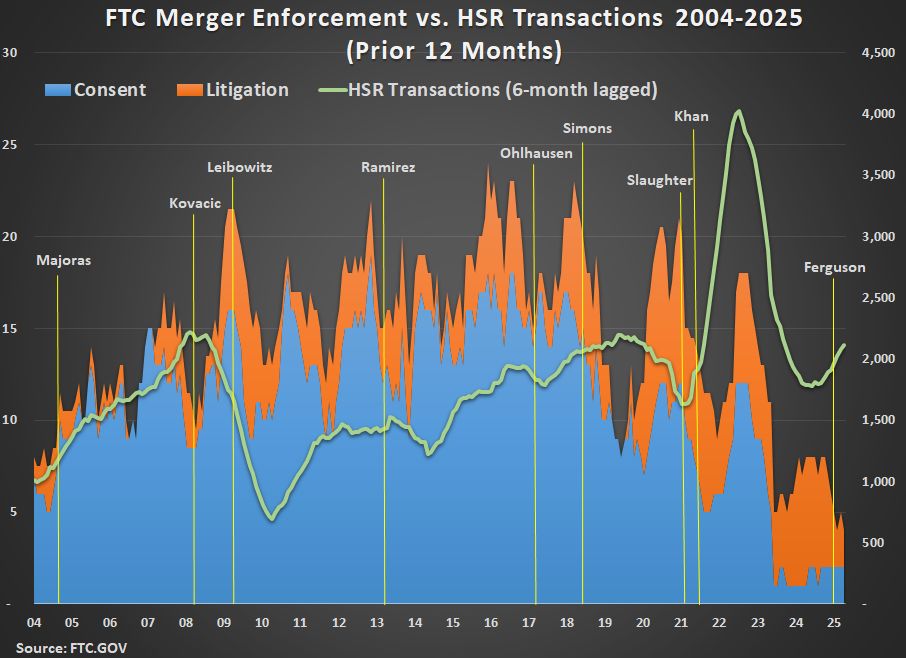

Another graphic shows U.S. merger enforcement versus reported Hart-Scott-Rodino transactions from 2004-2025.

In sum:

The chart shows a significant rise in litigation as a share of FTC’s total merger enforcement in the past eight years. Merger enforcement has fallen significantly under Khan’s tenure as FTC chair, especially in comparison to the number of HSR transactions. FTC merger consents have become relatively infrequent since 2023.

For just a bit more reading—still at the blog-post level—I’ll recommend two pieces written by another former FTC colleague (and ICLE academic affiliate) John Yun. Yun discusses the Antitrust Division’s now-settled case against Hewlett Packard Enterprise’s acquisition of Juniper Networks (here and here). John wrote—convincingly, in my view—that the case against the merger was deficient, partly because it seemed a weak structural case, and substantially because it failed to consider potential merger efficiencies and, specifically, the ability and incentive of a merged entity to more effectively challenge an industry-leading incumbent in Cisco.

Among other things, he suggests the need to “revisit the limiting doctrines placed on efficiencies altogether,” and, specifically, the refusal to consider “out of market efficiencies,” which can artificially restrict an accounting of likely merger benefits. (For a blast from the deep dark past of January 2024, here are Brian Albrecht, Geoff Manne, and yours truly on “The Conundrum of Out-of-Market Effects in Merger Analysis.”)

I would venture to suggest an institutional component to this: when agency staff at the division, or in the FTC’s bureaus of economics and competition, screen a merger while (a) looking for red flags that warrant a deeper dive and (b) overall, seeking to understand a deal in its entirety, including potential and likely efficiencies (or other merger benefits) and the likely incentives of a merged entity, among other things, then likely—and even plausible—merger benefits are commonly considered before there’s ever a decision to go to court to block the deal.

When staff have questions, the parties proposing the deal are given the opportunity to answer them. Under those circumstances, the agencies and their staff might rightly be skeptical of further efficiency defenses, and that skepticism might well be reflected at trial and, at least sometimes, in decisions.

But if there’s a policy that tends to oppose mergers generally, before substantial risks to competition are surfaced, then a rote denial of likely merger benefits will unduly skew merger analysis inside the agencies and in the courts. And that goes double against a background policy that’s skeptical of merger settlements.

The second of Yun’s two pieces was posted June 23. As it happens, just over two weeks later, on July 10, the Antitrust Division announced a proposed settlement in the case. HPE would be required to divest the HPE Instant On campus and branch business, and to license the source code for Juniper’s Mist AI Ops software, but the deal would otherwise be permitted to go through. So whatever the frequency and quality of settlements going forward, they are not wholly off the table, if ever they were.

Rounding up some more collective roundups, I’ll point to this newsletter from another FTC veteran, Bilal Sayyed (former director of the FTC Office of Policy Planning), in which he describes various ways in which federal enforcers in this administration seem to be departing from (or at least altering) policies of those in the last administration. It’s a good and useful summary.

I’ll also point to a regular column that’s always worth reading—Antitrust Antidote—by two more FTC veterans, Koren Wong-Ervin and Nathan Miller, who are joined by a third veteran, Jeremy Sandford, in the March-June 2025 edition. This one covers the FTC’s now-defunct case against the Microsoft/Activision merger, the mixed decision from the Eastern District of Virginia in U.S, v. Google, and the U.S. v. Live Nation case, among others.

I’ll get to some of these matters before long, but there’s plenty to read in the meantime.