Estimates in this brief were generated July 21, before the announcement of trade deals with Japan and the European Union. All data and code used in the Equitable Growth tariff analysis, including instructions to update the analysis with the latest tariff rates, can be found in our Github repository.

Overview

During his first term in office, President Donald Trump in 2018 made good on a campaign pledge to introduce new U.S. tariffs on imported goods—steel and aluminum in particular—in a purported effort to protect domestic jobs and shrink the trade deficit. Those tariffs largely targeted products from China—the world’s second-largest economy, largest single source of U.S. imports, and the United States’ preeminent geopolitical rival.

In the subsequent administration, President Joe Biden maintained many of the Trump tariffs and enacted a series of new targeted trade restrictions intended to protect U.S. industry and national security. The moves reignited a popular debate about the function and fairness of tariffs—a debate that weighed the costs for U.S. consumers in the form of higher import prices against the benefits for U.S. workers in the form of increased demand for domestically produced goods.

Many economists argued that targeted tariffs, and specifically those on some auto imports, for example, could benefit domestic industry without pushing the overall consumer price level higher. That logic was upended, however, when President Trump returned to the White House for his second term, promising national “liberation” through a series of sweeping tariffs against countries deemed to cheat the United States in international markets.

Rather than targeting a narrow industry or set of commodities, as he did in his first term, the second Trump administration’s tariff policy covers nearly all dutiable imports, with some limited exceptions. Energy and potash from Canada, for example, are subject to a lower tariff rate than the overall rate imposed on goods from Canada. Separately, U.S. automakers were awarded credits they can use to offset the cost of tariffs on imported materials, though these credits will be phased out within 3 years. (These commodity-specific exemptions are omitted from the baseline analysis in this issue brief due to limited public data on how industries source inputs.)

President Trump’s far-reaching tariff policy is sure to have deep and often contradictory economic consequences for the United States and the world. Some U.S. industries may indeed experience a revival, as their products become more competitive in domestic markets compared to tariffed imports. But it is unclear whether those potential benefits will outweigh the costs of tariffs, not only for consumers facing higher prices but also for U.S. workers themselves.

Retaliatory tariffs enacted by other countries on U.S. exports, for example, will harm U.S. workers as foreign demand for U.S. goods dries up. Also harmful to U.S. workers are the tariffs on intermediate inputs imported by domestic industries, such as the raw and finished metals used in auto assembly.

This Equitable Growth analysis focuses on the question of how tariffs on imported inputs could raise costs for U.S. industries and workers, and how those costs might be distributed geographically. More specifically, this analysis compiles data representing:

- How U.S. industries use and import commodities as inputs

- How a given tariff regime could impose additional input costs on U.S. industries

- How those additional costs could impact employment in key industries and geographic regions

While it does not directly calculate the cost of tariffs or their effects on employment, it does draw an empirical picture of how tariff costs could be distributed across industries, relying on a few key assumptions drawn from the available data.

In the spirit of open and equitable research, this analysis is published alongside raw and finished datasets, as well as the Stata code required to reproduce this work and generate new datasets of interest. The code grants users the flexibility to compile datasets of interest by industrial and geographic specificity and produce metrics to judge industrial exposure to imports and tariffs. (More information on the Stata code can be found in the GitHub repository.)

Tariffs pose a particular threat to U.S. manufacturing

Our analysis finds that U.S. manufacturing industries are clearly more exposed to tariffs on intermediate inputs compared to other U.S. industries, undermining a key Trump administration argument about the effectiveness of tariffs. Manufacturing industries—including the politically and economically sensitive vehicle production sector—will face increased input costs imposed by the very tariff regime intended to boost their competitiveness with imported final goods (finished cars, in the vehicle production example).

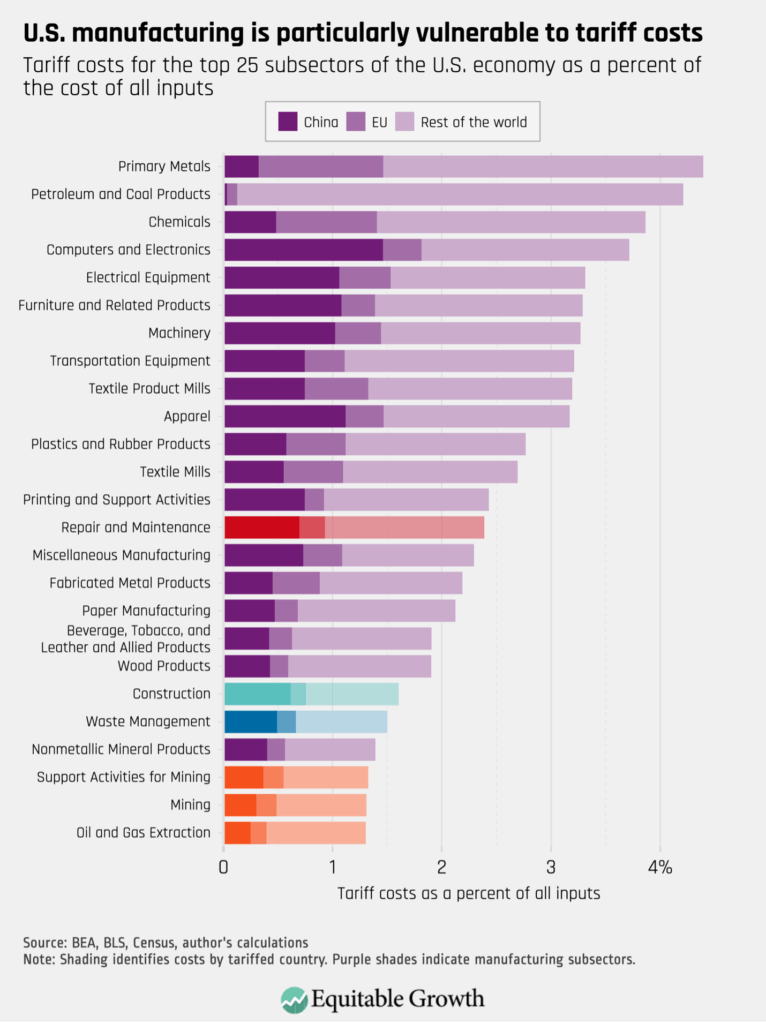

Importantly, manufacturing would likely be the most vulnerable industrial category regardless of the commodity or country specifics of a given tariff regime. Some manufacturing subsectors may be less harmed than others, but the overall reliance of the sector on imported inputs means manufacturing will face greater intermediate tariff costs compared to other industries. Indeed, of the top 25 subsectors of the U.S. economy that are most affected by tariffs, 19 are in manufacturing. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Before diving into more detail, it is important to note that this analysis produces two distinct yet important metrics to predict or track the impacts of a given tariff regime:

- An industry’s imported share of inputs, or the fraction of that industry’s inputs that are sourced from outside the United States. This measure represents an industry’s exposure to tariffs generally, before the application of any specific trade policy. In this analysis, this import share value is first generated at the specific industry-commodity level, showing import intensity for each input, before being aggregated at the industry level.

- Tariff costs as a percent of all input costs. After trade policy has been layered into the analysis, estimates of the costs of tariffs can be generated at the industry level, as a fraction of an industry’s total input costs. These tariff cost estimates are a representation of the hit to the profitability or bottom line of an industry as a result of a specific tariff regime. The baseline tariff regime modeled in this analysis includes all reciprocal tariffs due to come into effect in August, except those on Canada and Mexico (see the Appendix for further discussion).

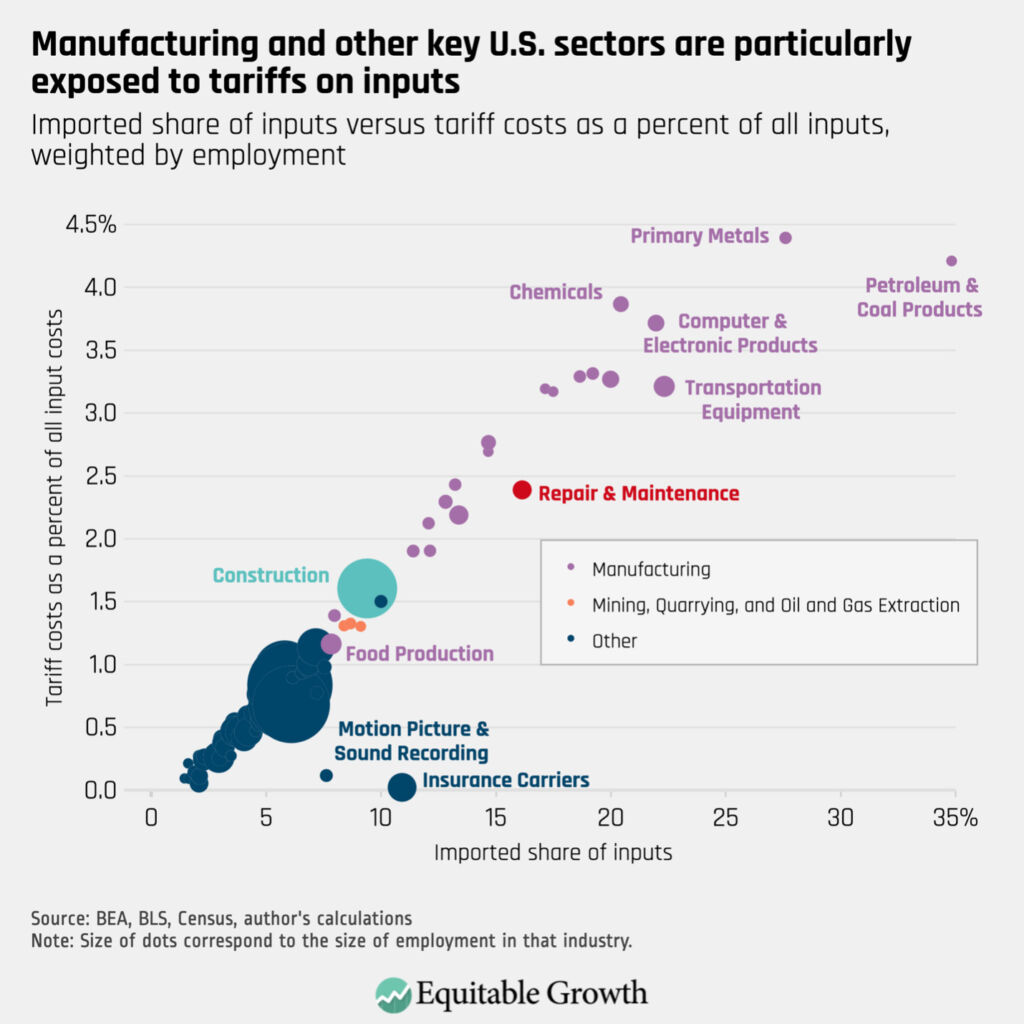

Figure 2 below plots the exposure rate of certain industries to tariffs using each of these two measures. The tariff cost measure reflects tariffs both threatened and enacted by the Trump administration, as discussed further in the appendix section. The measures produce nearly identical pictures of industrial exposure to tariffs, as the diagonal plot line makes clear. As we can see, both measures show particular vulnerability for the manufacturing sector, with the tariff cost measure showing most manufacturing industries facing cost increases of 2 percent to 4.5 percent. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

A few outliers do exist, including the movie and sound recording industry and insurance carriers (the dark blue outliers on the bottom of the graph) and the petroleum and coal products industry (the purple dot in the upper right corner). The former two are more exposed in the import share measure compared to the tariff cost measure because while they import an unusually large amount of inputs, they are primarily nondutiable goods: Insurance products imported by insurance firms and foreign films imported by domestic movie companies. The latter is an outlier because the overwhelming majority of coal and petroleum imported inputs are sourced from countries (mostly Canada, but also Mexico and Saudi Arabia) that are subject only to the 10 percent base tariff rate, compared to the much higher reciprocal rates imposed on many other countries, including China.

Impact on upstream industries

The construction industry (the teal bubble in Figure 2) faces relatively lower tariff exposure compared to manufacturing subsectors but still substantially more than other industries. This is due in large part to imports of raw materials that are often sourced from China. The repair and maintenance industry (seen in red in Figure 2), which includes auto repair shops and commercial and household equipment repair, is also highly exposed to tariffs. Mining and fossil fuel extraction (marked in orange in Figure 2) are less exposed to tariffs than manufacturing but are meaningfully more exposed than the rest of the U.S. economy.

These three groups—construction, repair and maintenance, and mining and extraction—in addition to manufacturing, are upstream in the U.S. economy, meaning their products are often used as inputs by other industries further down a supply chain or are used as infrastructure in the facilitation of economic exchange broadly. Domestic vehicle parts manufacturers, for example, will face additional costs as they import raw metals and finished components to produce engines, transmissions, brakes, and other systems.

Some of those domestic vehicle parts will be sold (with a mark-up to account for the tariff cost) to domestic auto producers and the domestic repair and maintenance industry. This will impose additional costs on these domestic producers, on top of the tariffs they have to pay directly on their own imported inputs.

In the case of construction, additional costs of imported materials will burden the building of transportation infrastructure, as well as commercial and industrial facilities. It also means residential construction will become more expensive, and projects will slow or halt, constraining the supply of new housing and potentially putting upward pressure on housing prices. These second-order costs are not captured in this analysis but could be an important focus of future work.

Impact in highly exposed industries

The particularly high tariff exposure of manufacturing and construction industries is important for the U.S. economy not only because those industries are upstream but also because they employ large numbers of people. More than 8 million workers were employed in construction in an average month in 2025, while nearly 13 million people were employed in manufacturing industries—more than 1 in 10 U.S. workers.

Numerous factors outside the purview of this analysis will dictate how domestic employers pass down tariff costs to workers, including union coverage, gender and race, and other workforce characteristics. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics says, for example, that more than 10 percent of construction workers and 7.9 percent of manufacturing workers are covered by a union contract, meaning those workers might be marginally more protected against tariff-caused job losses, compared to the average worker in the U.S. private sector, where the union coverage rate is 5.9 percent.

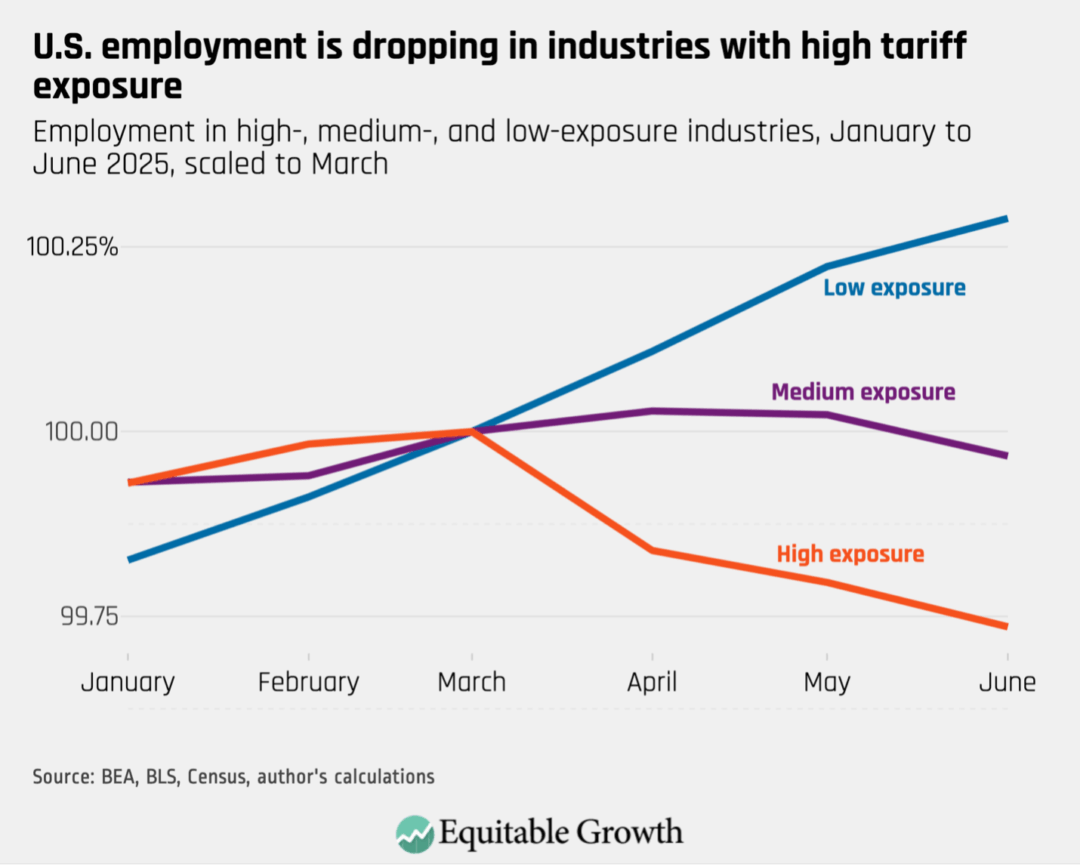

It is unclear whether those protections will be sufficient for firms facing estimated tariff-related hits to their bottom lines of 2 percent to 4.5 percent, as is the case in most manufacturing industries shown in Figure 2. Already, seasonally adjusted employment in highly tariff-exposed industries is beginning to decline. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Many highly exposed industries also are important to the stated national security goals of this and prior administrations—namely, the protection and cultivation of a domestic semiconductor and computer tech industry, including AI development, and reinvigoration of domestic energy production. Without targeted tariff carveouts, as the Trump administration has sporadically attempted, these nationally strategic industries will suffer.

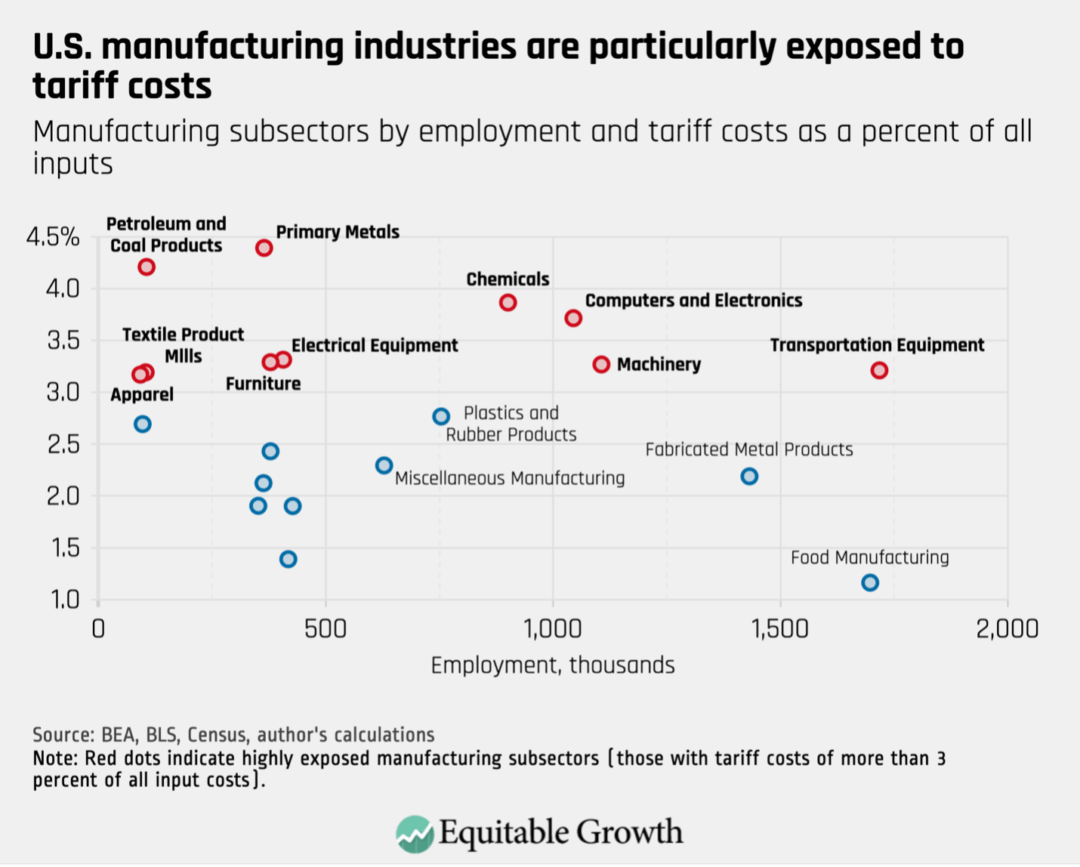

Computer and electronic product manufacturing, for example, is one of most highly exposed subsectors of the U.S. economy, importing more than 20 percent of its inputs and facing an estimated more than 3.5 percent increase in total input costs because of the current tariff regime. Similarly, though domestic energy production is less exposed—a little less than 10 percent of inputs are imported and estimated cost increases are close to 1.5 percent—even a modest shrinking of profit margins could disrupt production in an industry known for its high sensitivity to prices. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

While these industries important to national security may see a boon in tariffs on competitor goods, those same tariffs will increase input costs and mitigate—or even eliminate—any leg up in the market, creating political complications for the Trump administration.

Geographic impact of tariffs

Also likely to produce political complications for President Trump is the geographic incidence of tariffs. A core limitation of this analysis is that U.S. Census Bureau import data only captures a shipment’s initial destination rather than its final destination, so it is difficult to know how states will be directly impacted by tariffs on various countries or commodities.

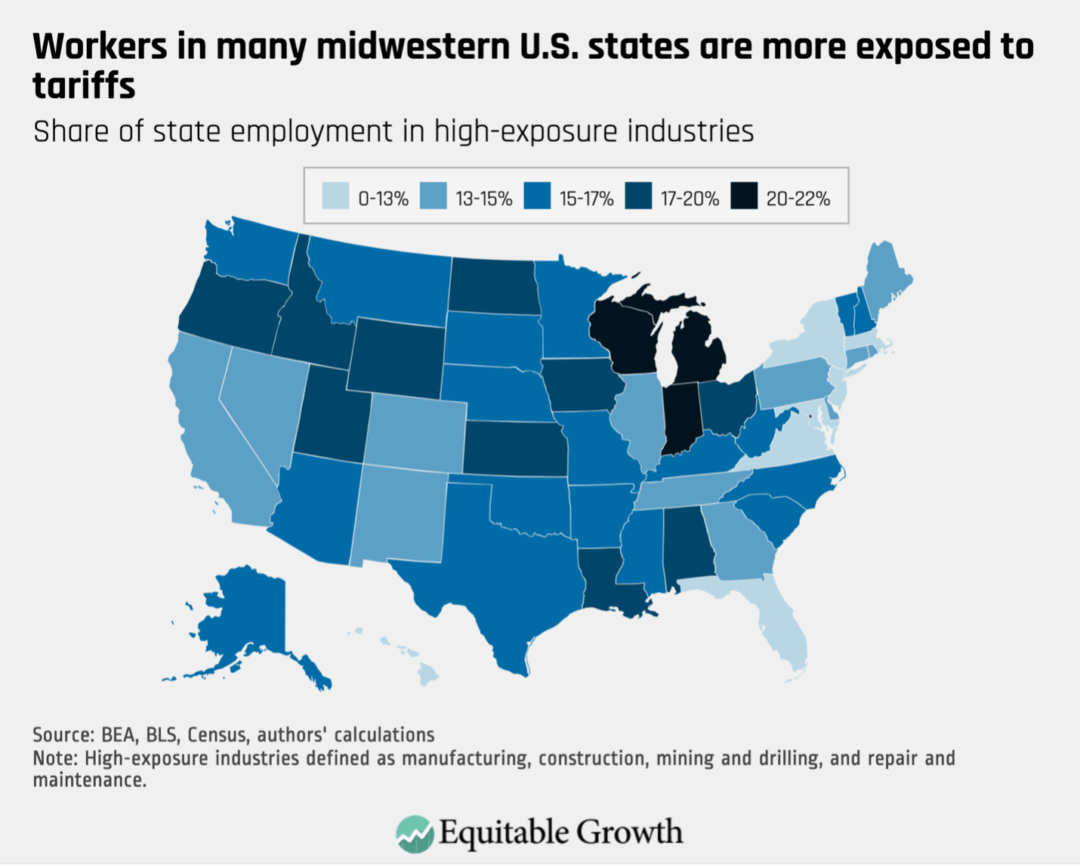

To paint a general picture of how states could be differently impacted by the current tariff regime, we use employment by industry in each state to construct a measure of relative industrial employment compositions. We determine states to be highly exposed to tariffs if a large share of state employment is in industries with high tariff exposure. Using this metric, we find that midwestern states, including Michigan, Wisconsin, and Indiana, will likely face higher tariff costs compared to other states. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

These high tariff costs could put pressure on many workers and their families in these politically important states, where votes on the margin have swung elections for one candidate or another in recent elections.

Areas for future research

This analysis should be seen as a foundation or a framework for estimating the potential industry-level effects of a given tariff and trade policy regime, providing several avenues for further research. The first option would be to combine this analysis of tariffs on intermediate inputs with comparable industry-level estimates of the effects of tariffs on final goods—both U.S. tariffs on imported competitor products and retaliatory tariffs imposed by other countries on U.S. industries’ exports.

Similarly, the positive effects of import substitution on domestic industry—for example, when U.S. steel producers see higher revenue as steel-consuming domestic industries reshore supply chains—are not captured by this analysis and could similarly be incorporated to provide a more complete picture of tariffs’ effects on the U.S. economy.

Additionally, tariff policy does not exist in a vacuum. The recently passed Republican budget reconciliation law will have broad and deep impacts on the U.S. economy, including on industries impacted by tariff policy. Many of the industries likely impacted by the budget law, including hospitals and doctors’ offices hurt by $1 trillion in Medicaid cuts, are not particularly exposed to tariffs directly. But the medical equipment and supplies manufacturing industry is both highly exposed to tariffs and potentially harmed by the law’s Medicaid cuts due to slowing demand for equipment from hospitals and doctors across the country.

As discussed above, workforce characteristics—including union coverage, race and gender identity, and immigration status—could determine how easily U.S. employers pass down tariff costs to workers in the form of stagnant wages, layoffs, or firm closures. Incorporating industry-level workforce characteristics from the Current Population Survey or other data sources would greatly improve the predictive capacity of this analysis.

Conclusion

This baseline prediction of how U.S. industries will be impacted by tariffs on imported inputs finds the manufacturing sector is highly exposed to tariffs, despite some exemptions granted by the Trump administration. Also relatively vulnerable to tariffs are construction, mining and energy production, and repair and maintenance.

The more than 23 million people employed in 2024 in these more exposed industries could face wage stagnation or even job losses as their employers seek to pass down the costs of tariffs onto workers. Considering the geographic concentration of the impact of the tariffs in midwestern and other electorally important states, the impact of the Trump “liberation” tariffs could reach beyond the economy or the specific industries most vulnerable to trade policy shifts.

Future research is needed to expand and further detail the potential impacts of tariffs and trade policy. This analysis can be used as a stepping off point for many avenues of future study, as it offers a novel interlinked dataset and code accessible to other researchers.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!