What is good management, and how is it transmitted across firms and plants? In a recent paper, we use survey and administrative data, coupled with a structural model of management, to explore these questions. We show that well-managed manufacturing firms—that is, firms that adopt more structured management practices described below—not only open and acquire more plants, but also close and sell more plants. Through this process, the firms transmit their management practices to new plants. These facts, taken together, imply that acquisitions can increase aggregate productivity by allowing well-managed firms to take over poorly managed plants and improve their management practices.

Measuring Management

We use two large-scale surveys to measure management practices: the U.S. Census Bureau’s Management and Organizational Practices Survey (MOPS), which covers manufacturing firms in the United States, and the World Management Survey (WMS), which covers manufacturing firms in thirty-eight additional countries. Both surveys pose a series of questions about three areas of management practices: monitoring, target setting, and people management.

The monitoring section of the surveys asks firms about how they track information to monitor and improve their production process. For example, plant managers are asked how many performance indicators are monitored at each establishment, how they are displayed, and how often they are reviewed by plant managers and non-managerial workers. Firms that track multiple indicators, display them clearly, and review them frequently receive higher management scores.

The target setting section of the surveys asks firms about how production targets are designed and how realistic they are. For example, plant managers are asked about the time frame and difficulty of meeting their production targets. Firms that have both short- and long-term production targets that are demanding but not impossible to achieve receive higher management scores.

Finally, the people management section of the survey asks how performance is incentivized for managers and non-managers through promotion, bonuses, and dismissal policies. For example, plant managers are asked if promotions are based solely on performance and ability, or on other factors such as tenure or family connections. Firms that base promotion and compensation decisions on individual performance receive higher management scores.

We use the answers to these surveys to create an overall management score for each plant and firm that ranges from zero to one, with higher scores indicating the adoption of more structured management practices. Using the MOPS in conjunction with other data from the U.S. Census, including the Census of Manufacturers and Longitudinal Business Database, we can track plant openings, closings, and acquisitions, enabling us to investigate the relationship between the management practices and dynamics of a given firm.

Management and Firm Growth

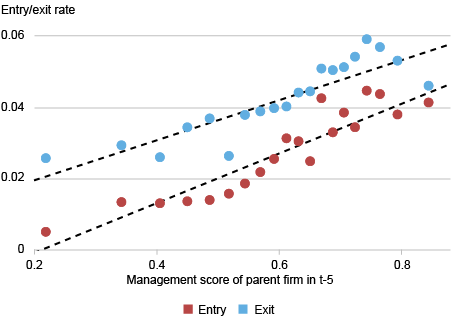

We find that well-managed firms in the MOPS exhibit higher plant turnover: they open, close, acquire, and sell more plants.

We consider four margins of firm growth: entry (plants that are opened), exit (plants that are closed), acquisitions (plants that change ownership to the focal firm from another firm), and disposals (plants that change ownership from the focal firm to another firm). We calculate the entry rate as the number of plants that were opened divided by the initial number of plants managed by the firm, then measure these growth rates over five-year intervals. (We perform similar calculations for the other margins of growth.)

The chart below shows that firms with higher management scores open more new plants. This comports with prior evidence that well-managed firms are generally more productive and grow faster. Interestingly, firms with higher management scores also close a larger share of their plants. While prior research suggests that well-managed plants are less likely to exit, these results are limited to “surviving” firms that are present throughout the five-year period. So, although individual well-managed plants are less likely to exit, well-managed firms still exit a larger share of plants.

Well-Managed Firms Have Greater Entry and Exit Rates

Notes: Data from MOPS of firms that had at least one plant in the MOPS in 2010 or 2015. Only stayer firms are included, i.e. those that had one plant present in 2010 and 2015 or 2015 and 2019. The entry (exit) rate is defined as the number of manufacturing plants entering (exiting) between year t-5 and year t divided by the total number of manufacturing plants at the firm in year t-5. All rates are winsorized at the 99th percentile. Plot shows means for 20 equal-sized bins of parent firm management scores. Bin scatters include fixed effects for the modal 3-digit NAICS industry and modal state for plants in the firm. Growth rates are defined from 2010-2015 and 2015-2019 (the latest available data at the time of writing). N=32,000 firms.

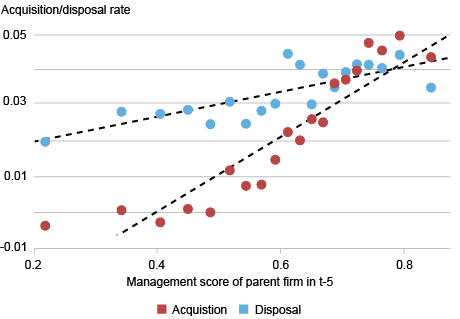

Echoing the results for entry and exit, the next chart extends this analysis to acquisition and disposal of plants on the M&A market. The data show that well-managed firms acquire more plants, and that they also dispose of more plants.

Taken together, these findings indicate that firms with better management practices exhibit greater plant turnover. This trend parallels patterns observed in private equity takeovers, where high rates of plant churn are common. Notably, on both the entry/exit and acquisition/disposal margins, the net gains are positively correlated with management quality, so well-managed firms still grow more overall.

Well-Managed Firms Have Greater Acquisition and Disposal Rates

Notes: The sample, plot construction, and controls are identical to those in the chart above. The acquisition (disposal) rate is defined as the number of manufacturing plants acquired (disposed of) between year t-5 and year t divided by the total number of manufacturing plants owned by the firm in year t-5.

Transmission of Management Practices

Given the relationship between management quality and plant turnover, we next turn our attention to how management practices spread across plants within a firm. We are interested in understanding the extent to which management is non-rival. That is, can management practices be shared freely across plants within a firm as a type of technology, without diminishing their availability? Or, is management more akin to capital, with the presence of specific managers or equipment being necessary to spread management practices across plants?

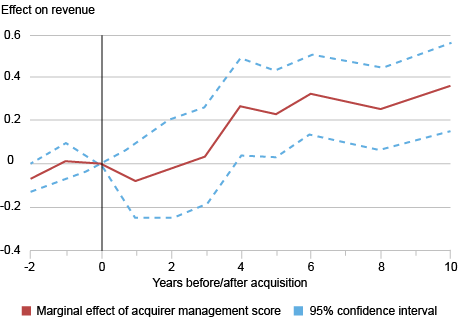

We find evidence that management is at least partially non-rival: good management practices spread to new entrant plants and to newly acquired plants. In the paper, we show that the management scores of new entrant plants are positively correlated with the management scores of their parent firms in the MOPS. We also show that acquired plants in the MOPS converge in management to their acquirer firm. Plants that are purchased by well-managed firms from poorly managed firms increase their management scores and revenue.

We use WMS data to take a closer look at how management is transferred through acquisitions, running event study regressions to assess the effect of acquirer firm management on target firm performance. As shown in the chart below, we find that acquirer management scores have a positive effect on target revenue. Interestingly, the positive effect of acquirer management on revenue doesn’t show up until four years after acquisition, suggesting that it takes time for the purchased firm to implement the management practices of the acquiring firm. In the paper, we show that takeovers by well-managed firms also cause acquired firms to increase their productivity and decrease their employment and capital, suggesting that they can produce more efficiently post-acquisition.

Performance Rises after Acquisition by Well-Managed Firms

Notes: Data from 1,247 targets acquired by 687 firms in the World Management Survey from 1997 to 2018. X-axis shows years since acquisition, benchmarked to zero, and y-axis shows marginal effect of acquirer management score on target revenue.

Aggregate Implications

In the paper, we develop a model of firm dynamics to explore the implications of these relationships for aggregate outcomes. Using the model, we assess the effect of restrictive M&A policy and find that banning acquisitions has negative effects on productivity and output. When we turn off M&A, average management quality and average revenue both decrease by about 13 percent. This is because acquisitions reallocate plants from poorly managed to well-managed firms, which increases overall output and management quality. This highlights the important role of the M&A market in resource allocation.

We also use the model to estimate the contribution of management to productivity gaps across countries, and find that, on average, management quality accounts for a 12 percent productivity gap with the U.S.—about one-fifth of the total average productivity gap between non-U.S. firms and U.S. firms. The bulk of this management gap is explained by absolute differences in management practices (that is, firms in other countries on average exhibit less structured management practices than the average practices in the United States), but one-quarter is explained by reallocation. That is, the covariance between management quality and firm size is larger in the United States, suggesting that U.S. firms are better able to allocate resources to well-managed firms. These findings are consistent with the idea that the allocative effects of management, realized through organic growth and acquisitions, have important consequences for aggregate output.

Nicholas Bloom is the William Eberle Professor of Economics at Stanford University.

Jonathan Hartley is an economics Ph.D. Candidate at Stanford University.

Raffaella Sadun is the Charles E. Wilson Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School.

Rachel Schuh is a research economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

John Van Reenen is Ronald Coase School Professor at the London School of Economics and Digital Fellow, Initiative for the Digital Economy at the Massachusetts Institute for Technology.

How to cite this post:

Nicholas Bloom, Jonathan Hartley, Raffaella Sadun, Rachel Schuh, and John Van Reenen, “How Firms Spread Good Management,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, August 13, 2025, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2025/08/how-firms-spread-good-management/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s). Further, any views expressed are those of the authors and not those of the U.S. Census Bureau. The Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board and Disclosure Avoidance Officers have reviewed this information product for unauthorized disclosure of confidential information and have approved the disclosure avoidance practices applied to this release. This research was performed at a Federal Statistical Research Data Center under FSRDC Project Number 1694.