What learning about the keystone nut trees showed me was that, actually, there is no line, and these are all pieces of the same world.

Introduction

Photo by Joe Navas.

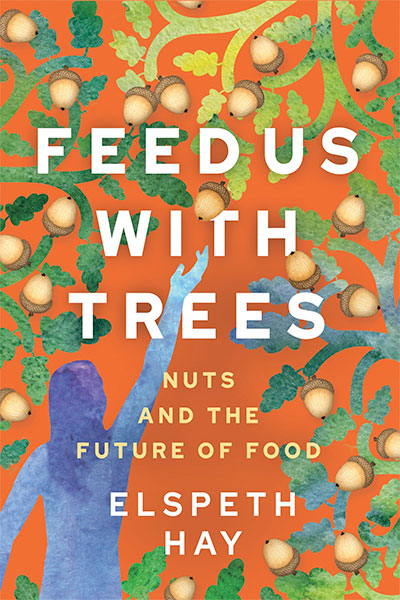

Elspeth Hay is obsessed with studying the ways humans meet their material needs, namely how we feed ourselves. As a public radio reporter, Hay started The Local Food Report, a weekly segment that focuses on the people, means, and places that provide sustenance for the residents of Cape Cod and its outlying islands off the coast of Massachusetts. When, in the course of her reporting, Hay came upon the notion that humans could eat acorns, it altered everything she previously believed about ecosystems, agriculture, and the human impact on the environment. The idea for her book Feed Us with Trees: Nuts and the Future of Food (New Society Publishers, 2025) took root.

Hay spent five years researching nut trees as keystone species, Indigenous methods of forest tending, and the history of Euro-Americans’ relationship with land, among many other aspects of rethinking the role of humans of the planet. The result is a book rich with insight, information, and inspiration.

I discovered Hay’s book and her work as a result of my own obsession with healing the human relationship with the more-than-human world. We spoke via the internet, but we’re both hikers in the Northeast, so I can easily imagine us huffing up a peak together, chatting among the birds.

The story I call “no farms, no food”—the idea that natural or wild ecosystems don’t have food for humans—wasn’t an accident. It was directly tied to colonialism and capitalism and the birth of those systems.

Interview

Cara Benson: This book seems like it came out of your longstanding interest in local food systems—both the ecological and the human aspects of local food—which has been evident in your reporting. What drew you to food as a subject?

Elspeth Hay: I think food was one of the only real avenues that I was exposed to as a young person as a way to both connect to the natural world and meet a human need. My mom worked for an outdoor education organization called Chewonki, which started a semester program, and I went there my junior year of high school.

I’m not sure I fully knew what I was getting into, but when I got there, there was a huge focus on local food production. We had a farm and we planted seedlings and birthed lambs and were an integral part of the work there. That’s where I got interested in local food as a way of getting into something positive, because so much of what I knew about our human interaction with the environment was negative. At Chewonki I saw a way we could have a positive impact.

When I came home from that semester, that learning snowballed into other things. I did a project my senior year with a farm in our town producing some marketing for them about why it was important to eat local. We made a sign with broccoli and apples that said, “Put a face to your food.”

I also really liked the people I met in the local food world. Everyone seemed to want to do something good, and I enjoyed that.

Cara Benson: To be clear, when you say that this was a way do something good, you mean the local aspect of farming, because in the book you delve deeply into farming as a problematic turn in human culture.

Cara Benson: To be clear, when you say that this was a way do something good, you mean the local aspect of farming, because in the book you delve deeply into farming as a problematic turn in human culture.

Elspeth Hay: Yes, the local. During that time period when I was first getting interested in local food— this was around 2007 when I think “locavore” was the word of the year—there was a lot of buzz about it for a while. Much of the conversation was about distance traveled from farm to fork and less pesticide use. Less chemical use. The fertilizer at the farm where I went to school came from the horses, not from an agribusiness somewhere 3,000 miles away.

But it was still very much part of this narrative, which I hope I expose and maybe shift in the book: that humans can’t really be ecologically good; we can only be less bad. But that was the most hopeful thing I had in that time period, and so I grabbed onto it.

Cara Benson: I imagine that many readers of this conversation understand well that industrial agriculture is a problem, from its monocultures to use of pesticides, like you mentioned, to breeding seeds to withstand chemicals—all the nightmares that are associated with Big Ag. It’s obviously in the culture and has been for a while to talk about organic farming and regenerative farming as an answer to this.

Feed Us With Trees is clearly situated within this conversation, but it’s bringing forward the angle that the nut tree is a keystone species around which so much food production can center. How would you see your focus in the context of this larger conversation of organic and regenerative farming?

Elspeth Hay: I don’t think positive change in the food system has to mean no traditional row crop farming and instead have all tree crops. I still want to eat lettuce, and I like broccoli, and so on. What fascinated me when I first learned that we can eat acorns, which really just blew up my brain, was it got me to rethink this line that we’ve drawn between the human world and the natural world.

I’ve felt that line my whole life. On the one side, there are wildlife and ecosystems that we’re trying to preserve and maintain for wildlife. On the other side of that line, there are humans and our farms and we’re not part of the wild world or the natural world. Before I learned about acorns I saw it as: we ruin a landscape farming in an industrial monoculture or can maybe do less bad if we’re on a smaller farm with regenerative practices and encouraging pollinators and diversity of species.

But what learning about the keystone nut trees showed me was that, actually, there is no line, and these are all pieces of the same world. The same ecosystems. As I traced it back, I began to see the roots of that line in colonialism and the European diaspora and arrival in North America. So many of our farm species in mainstream American culture are species that European settlers brought here that were parts of native ecosystems in Europe.

Now those species have been out of their native context here for the past 500 years—species like wheat, cows, leeks, etc., that are native in Europe, but not here. When you overlay that with all of the cultural issues, because obviously it’s not like that’s true of every species—we’re farming American species as well like tomatoes and corn—but a story I have come to believe is that a part of the origin of that line was that farms and the species traditionally on them came from home for the settlers, and the nut tending practiced by Indigenous groups here came to be seen as separate, different. Europeans came to this new place and were never fully integrated here, or haven’t merged these ecosystem views.

It’s interesting because it’s really not about species, necessarily. There were nut trees that were tended by European people, but as colonial rule spread this mindset shift happened. There became this real divide between people who farmed fields and people who tended native ecosystems, including nut trees, for food. I think bringing both pieces of that into the regenerative conversation is really important. I don’t think we’re going to be able to move forward without reckoning with that history and with some really harmful narratives written during that time period that continue to be perpetuated.

I remember thinking that every story I read about Indigenous people and American settlers was always told the same way: that the Europeans came here because it was a land of opportunity.

Cara Benson: Regarding the historical piece in the story and the bridging of those two cultural approaches to land, you’re specifically referencing the Indigenous and the European. This brings to mind your work in the book to connect to your historical lineage as a Euro-American, looking for where the break in European commoners’ connection to land occurred; that there had been a European land-based culture that got disrupted. What led you to look at that in terms of your ancestral history?

Elspeth Hay: I mentioned in the book the story of the American Girl doll Kirsten Larson. I must have read those books a hundred times as a kid. I remember thinking that every story I read about Indigenous people and American settlers was always told the same way: that the Europeans came here because it was a land of opportunity.

That was one component of the story. Another component was about Indigenous people living in harmony with the landscape, and that’s also a trope in its own right. But there was this sense that one group of people could fully meet their needs from the land. And then these other people could not and had to create heavily farmed landscapes to meet their needs. That just never made sense to me.

When I started researching these keystone nut trees and discovered that humans all over the northern hemisphere used to eat them and tend to them as this key piece of a productive human foodscape, I wondered how my people got disconnected. How do you go from being totally connected to a place—and I think in retrospect the question was also: How do you go from living in a place for generations and believing that these trees are sacred, to thinking “I’m going to cross the Atlantic for an opportunity”?

That’s really hard for me to imagine. I’m a homebody, so the idea of crossing the Atlantic for an opportunity just doesn’t resonate. Maybe for some people it would, but when I started going back through the history, I learned about a period called the Enclosures—this sort of internal colonization before the external colonization where indigenous Europeans were in a variety of ways separated from our ancestral lands. Reading about it, I identified this sense of loss and trauma that we don’t talk about. I think that’s at the bottom of a lot of cultural challenges that we have now, systemic challenges, and also that talking about it and acknowledging it are really crucial to solving so many problems. It’s really hard to solve a problem that you haven’t acknowledged—this disconnect from land.

If you put yourself in the shoes of some of these people crossing an ocean and coming to a new place, maybe you’ve been kicked off common lands in Europe or you’ve been persecuted as a witch for your medical knowledge of certain species, or tending or worshiping trees makes you a pagan and that’s not okay. You’re being persecuted religiously or for trying to tap into these common resources that used to be legally accessible and suddenly are not.

Of course you would just sort of shut that down and think that’s not safe, that’s not knowledge I’m going to talk about. I’m going to go into this more mainstream farm conversation and go get myself some land and have a farm and try to forget that, because that was not a good scene. It was really important to me researching the book to understand that part of the history of European connection to land that was broken and then to weave it through the story.

Cara Benson: The story of the destruction that the settler-colonial approach wreaked on Indigenous people and on their relationship with the land, as well as on the land itself, isn’t a new story, of course. But the specifics you were after in the research—particularly the framing of farming as a more civilized or evolved practice and that something like foraging was “lazy” or “savage,” and how that also impacted Europeans who were living off common land before they crossed the Atlantic—seems to shift the emotional tone of the story from stereotypical white guilt to something more productive. Your attitude in that quest to understand and to elucidate more specifically the mechanisms of this destructive past feels important.

Elspeth Hay: I deeply believe that the current system we’re living in is harmful to everyone living under it. Not to the same degree. Obviously, some people are suffering more under this system than others. But I so strongly believe that this system is good for no one. It’s not even good for the people who are getting the best out of it. Any system that is destroying life on Earth is by definition not a good system for people trying to be alive on Earth.

Species are going extinct. We’re losing biodiversity. We’re losing ecosystems. We’re losing topsoil. We’re losing clean water, clean air. So these nut trees offered this amazing lens to look at that loss—and that challenge—because they hold so many solutions. In becoming disconnected from them, all of us have lost a lot.

So many people I spoke to about oaks, in particular, talked about how it’s really hard to work with oaks in our current economy and political system. They mast, right? They don’t produce on this regular annual schedule. They have this sort of irregular production where they’re going to give you a lot of acorns one year and then not so many acorns another year. They’re not an economic product. People are not out looking to buy acorns.

One person I spoke with, a man named Justin Holt of the Asheville Nuttery, told me they’ve had a really hard time with oaks. They make acorn oil and work with acorns in other ways, but it’s been really hard in our economy. He thinks that’s kind of a good thing because not only do these trees offer this healing ecological pathway in terms of showing us how humans can be a keystone species by tending to these trees that support countless species of other life, but also, they don’t really fit into this economic system, and we need a new economic system to regenerate life instead of gambling with it, which is how I see our current system.

That ties into another thing at the heart of the book, which is ultimately what I discovered when I went down that pathway of asking what happened to my ancestors that they became so disconnected from land. The story I call “no farms, no food”—the idea that natural or wild ecosystems don’t have food for humans—wasn’t an accident. It was directly tied to colonialism and capitalism and the birth of those systems. Those systems aren’t possible without the “no farms, no food” story being believed by a large segment of the public. I think that even just talking about the fact that you can eat acorns and that there is this free, abundant, life-supporting food all around us is actually kind of a revolutionary thing.

Cara Benson: When I see the “No Farms No Food” bumper stickers, it’s usually referencing small farms that are largely perceived of or presented as the alternative to Big Ag, right? As a resistance stance and not the initial story that the lords of the land used, which you present in the book.

Elspeth Hay: Yes, and I’m very pro small farm. I think that’s a rallying cry for small farmers and that is also important. But it’s also a very succinct description of this older story, and I hope the farmers will forgive me for borrowing it.

Many fire ecologists and historians consider humans to be the keystone species for fire on Earth, and they see this as our ecological role. This is our niche.

Cara Benson: You mentioned, and cover this beautifully in the book, the idea that humans can be a keystone species in the way we tend to these nut trees. This is obviously counter to that divide between the wild and the human, and the idea that I think a lot of white environmentalists grew up with, that humans need to stay separate from the land for it to heal. Or to do less bad as you’ve been talking about.

Instead—and Robin Wall Kimmerer and so many others have been addressing this—these trees show us that the land actually needs us. You write about humans as the fire species and about prescribed fire, which you now take part in. The story of this book is also the story of your own personal relationship with land undergoing a transformation.

Elspeth Hay: I grew up inside that white environmental narrative that the best thing that we can do is shrink ourselves, remove ourselves, become small. I had an eating disorder in middle school, and looking back on it I think that was in part a response to this feeling that we’re bad. If we can just need less, take up less space—and I think that’s a story that’s told especially to young women…. But this idea was prevalent, that we’re born bad and we’re not like all the other species in the natural world.

I talk in the book about how my parents were birdwatchers. We looked at every bird and they would always explain how perfectly adapted it was to place and how it was an important part of the place and the jobs that it was doing, the ecological niche it was filling. I never saw us having a job or a niche. When I think about it now, that makes me so sad. It’s such a sad way to exist, to not see yourself as important and vital to the place where you live.

That really started to change for me when I got to know Ron Reed, who’s a big part of the book. As we got to know each other, he was describing to me his intersecting religious and ecological beliefs as an Indigenous Karuk person and describing humans as this vital species that’s needed to put fire on the land. He would tell me every call, “Fire is medicine, fire is medicine.”

I’m still absorbing that lesson. I don’t think you undo a lifetime of conditioning in a few years, but as I started to try to understand what he was saying, I learned more about the history of fire on my own landscape and was really surprised to find that fire has been a part of the Northeast for a really long time. I never heard about wildfires or prescribed burns growing up.

Many fire ecologists and historians consider humans to be the keystone species for fire on Earth, and they see this as our ecological role. This is our niche. You think about an animal; there are other keystone animals like a beaver. There have been some great books recently about beavers and how critical they are to creating wetlands and all these really important habitats. And elephants. We recognize the roles of other species.

But I think in part because of this historical trauma that connecting to land was dangerous for a lot of people and has been for a long time under colonial systems, the idea that we could be a keystone species had literally never occurred to me. I thought we were the opposite of any kind of critical keystone species. Think about post-apocalyptic movies and books where the Earth is thriving and it looks so much better without us; all the other species are flourishing as a result. This is not a very accurate perception of what would happen if we disappeared.

Yes, life would go on. It would also change. These keystone nut trees rely on us and our fire for their regeneration. Some of the fire statistics are really interesting. A very large percentage of all fires that happen in North America are started by humans. Even now in this era of fire suppression, when we are trying so hard not to start fires, we are still the largest cause of fire.

Photo by Elspeth Hay.

Cara Benson: I think both the L.A. fires and the devastation in Hawaii were in part a result of human energy systems, right? There’s the possibility that they were started by utility companies.

Elspeth Hay: I just wrote an op-ed about intentional burning on Cape Cod where I live, and I got a response that said basically, “I don’t see wildfires starting here. There’s no lightning striking.” I think we have this image in our heads of a wildfire started by lightning. But actually the vast majority of fires, whether they’re wildfires or any kind of landscape fire all over the world, are started by people. We can see that as a bad thing.

But let’s look at the equations for photosynthesis and combustion. There are the different molecules that photosynthesis puts together, and then combustion is actually just photosynthesis in reverse. So any time that there’s plant life, there’s also going to be fire. We’ve evolved as this fire animal, and we play a critical role in a lot of ecosystems. Learning that and getting trained in prescribed fire and going on burns, having a job to do taking care of these other species, has been a transformative experience.

Cara Benson: I love all the material in the book on forest succession and the idea that pruning trees, whether by coppicing and pollarding or with fire, winds up actually being more productive and sequestering more carbon than what I might call more obvious-looking old growth. These managed trees are still old growth, they just don’t look like old growth the way I typically envision it. I don’t think you or I are saying here to chop down the centuries-old growth, but that there’s a place for also being intentional with managing these trees.

Elspeth Hay: Something that comes into that is acknowledging and accepting that we have material needs, and if we want to stay alive we’re going to have meet them one way or another. Euro-American culture is often looking for this pure, clean solution. It can be both. We can have an old growth forest, and we can have these human-tended landscapes that are meeting human needs and supporting a lot of other species. Coppiced nut trees or coppiced willow trees are storing carbon in the ground and then sending up new shoots year after year after year. Meeting our needs can be really beautiful. It doesn’t have to be this destructive act or even a less bad act. It can be a positive act.

Cara Benson: That brings me to your obsession with cracking the code on the yield issue and that aha moment around externalities. Like, of course, in capitalism, there are externalities. That’s what corporations are based on—their fiduciary responsibility to shareholders and externalizing any costs or adverse effects. It never even occurred to me that in the yield issue, in the scale issue of feeding the world that Big Ag uses to justify itself, there were externalities in considering how yield is calculated.

Elspeth Hay: My conversation with agronomist Ricardo Salvador was such a lightbulb moment. He said yield is a ratio. You can’t just count what you’re getting out. You have to count what you’re putting in, too. When we talk about the land required to feed the world and how we need these high-yield farms, these agribusiness industrial monocultures, because they yield more, we are only counting the land where the food is being harvested. We’re not counting the land that was mined to build the tractor. We’re not counting the land where the fuel was extracted to run the tractor. We’re not counting the land where the seed was grown. We’re not counting any of the other land involved in this production. When you do count that land, this form of agriculture is not high-yielding. It is low-yielding.

One of the farmers I interviewed for the book, Philip Rutter, explained it to me in a way that made sense, which was through the lens of photosynthesis. If you think about the photosynthetic capacity of a field of grain versus a forest, it doesn’t compare. A forest has more photosynthetic ability just by height and reach and the amount of photosynthesizing plant tissue involved. He shared with me a study that compared an oak savanna to a cornfield in terms of photosynthesis. The oak savanna produces more energy. It has these huge trees. It’s like saying this six-foot-seven man can run faster than the toddler. Well, yeah. They’re able to use more energy.

When you have a monoculture, you’re also often wasting what you are getting from that system. In a traditional polyculture system, you’re taking the straw for bedding. You’re taking all these different products, and any time you add diversity and layers into a system, it’s inherently more productive. And you’re not relying as much on these huge other plots of land to overproduce in this one spot.

Learning to become a part of a place has been and will continue to be a lifelong practice for me.

Cara Benson: You describe yourself as being committed to place-based living. As someone who is also interested in fostering connection to place, I’d love to hear what that means to you.

Elspeth Hay: Learning to become a part of a place has been and will continue to be a lifelong practice for me. I think that it’s an inherent human tendency to want to connect with the places that we are a part of. The human connection is vital, and I think that a lot of us are doing a better job with that. But there’s also this connection to meeting material needs from place and relearning lost skills to do that.

A lot of place-based skills are having a revival, like weaving and fermentation. I used to look out my window and, beyond food from a garden, I couldn’t really imagine meeting any of my needs from this place where I live. It feels like this doorway has been opened where I realized, “Oh, I could make a basket. I could carve a spoon or I could weave nettle fibers to make a bag.” That will never stop exciting me.

But there’s this other layer that feels vital, too, which is being connected in ceremony both to people and place and doing it in a way that feels authentic and is building culture. You hear people talk about appropriating other cultural rituals and ceremonies. I think that was another piece for me of going back into the history and the lineage and trying to understand what my people did historically. How do all of us who have lost our indigenous connections to place bring ecological ceremony back into our lives, in connection with people and meeting our ecological needs and the needs of other species in a way that feels authentic and not phony?

I’m not going to figure it all out in my lifetime. That’s generational work, but that’s work I’m starting to do.

Cara Benson: Which leads perfectly into my last question for you. What’s next on your horizon?

Elspeth Hay: In addition to connecting with people around the book, a friend and I have started a group we’re calling Commons Keepers. We got some funding to do our first gathering this year. It’s an initiative to do that work of reconnecting ceremony and local people and meeting our material needs in place… back to the idea of the commons and how vital that’s been to human culture over millennia. I’m incredibly lucky to live in a place where we still have a commons. It’s different than historical commons, but 70 percent of the land where I live is still protected—knock on wood—by the federal government.

There are so many different ways here of making a living from the commons and not just in terms of resource harvest and extraction, but also restoration, teaching, surfing. I have friends who make shell jewelry, friends restoring rivers, friends growing oysters. So it’s about connecting young people, in particular, to these lifeways and presenting an alternative narrative to this idea that success is moving away from where you grew up and getting a big job in the city. We’re presenting the idea that success can mean staying rooted in a place and caring for it and learning how to do that in connection with humans and all the other species around us.

Learn more about Elspeth Hay at elspethhay.com.

Cara Benson is a writer dedicated to the wellbeing of the planet. Her work has been published in The New York Times, Boston Review, Orion, Sierra Magazine, and The Brooklyn Rail, and selected for Best American Poetry. She has received a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship and wrote a series on walking in the woods for the Best American Poetry website. Her memoir, An Armsfull of Birds: A Field Guide to Love, Loss, and Commitment, is due out in spring 2026 from HCI Books. She lives in a former church in the ancestral homelands of the Stockbridge Munsee Mohicans.

Cara Benson is a writer dedicated to the wellbeing of the planet. Her work has been published in The New York Times, Boston Review, Orion, Sierra Magazine, and The Brooklyn Rail, and selected for Best American Poetry. She has received a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship and wrote a series on walking in the woods for the Best American Poetry website. Her memoir, An Armsfull of Birds: A Field Guide to Love, Loss, and Commitment, is due out in spring 2026 from HCI Books. She lives in a former church in the ancestral homelands of the Stockbridge Munsee Mohicans.

Read Cara Benson’s interview with farmer and food justice activist Leah Penniman: “The Legacy of Seeds.”

Header photo by Alicja, courtesy Pixabay.