The Verde River is one of the last free-flowing rivers in Arizona, winding through what’s known as the Verde Valley before feeding into the Salt River. Agriculturally, the valley is relatively fertile, supporting crops like sweet corn, alfalfa, peaches, and pecans, as well as a small wine industry. Recently, though, residents have found that the water below their feet is drying up.

Faith Kerns grew up in the area, and her parents still live in her childhood home. This summer when they tried to turn on the garden hose, which is connected to their groundwater well — a common source for household water in the region — nothing came out.

“We’ve had some challenges here and there, but it’s definitely gotten worse over the last few years,” Kearns, who is the director of research communications at Arizona State University, told Grist.

Arizona is far from the only place where groundwater is in big trouble. According to a study released last week in the peer-reviewed academic journal Science Advances, fresh water has been declining at an alarming rate since researchers began observing global groundwater in 2002, creating areas of “mega-drying” that cover much of the Northern Hemisphere.

Although climate change is a contributing factor, with elevated temperatures sapping moisture out of the ground, the main culprit is overpumping of groundwater. After that water is put to human use, it escapes into the ocean where, the study found, it has contributed more to sea level rise than the melting of the Greenland ice sheet. Groundwater is responsible for roughly 44 percent of global mean sea level rise, compared to about 37 percent from Greenland and roughly 19 percent from melting in Antarctica.

The fact that “human management of water resources has such a significant effect on sea level rise, I think that has not been seen before,” said Martin Stute, a hydrologist at Barnard College who did not contribute to the study. He pointed out that even the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is still characterizing the transfer of groundwater to the ocean as a fairly minor addition to sea level rise.

Unless stringent water management policies are implemented on a global scale, the Science Advances study’s lead author, Jay Famiglietta, warns that the consequences could trigger extreme political instability, given that 75 percent of the world’s population resides in countries affected by this extreme drying. “What this study makes clear is that the world is looking at incredible sea level rise,” he said. “I think threats to food security and food production [aren’t] receiving enough attention.”

Such policies may not be forthcoming anytime soon. The United States, which sources half of its drinking water from groundwater, has no unifying water management plan, instead relying on a piecemeal local network of regulations. California passed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which aims to regulate water withdrawals and prevent aquifer exhaustion, in 2014, but the state isn’t expected to reach sustainable water use patterns until the early 2040s. Other states like Louisiana and Maine grant landowners “absolute dominion” over groundwater under their property — meaning any landowner can draw endlessly from their well, even at the expense of their neighbor, even as aquifers are depleted and threatened by saltwater intrusion.

In some areas of the country, so much water has already been drained that the aquifers have collapsed in on themselves, explained study co-author Hrishikesh Chandanpurkar. This causes land subsidence, damage to infrastructure, and compounding sea level rise in coastal areas. Sometimes, the collapse is irreversible, meaning a given region has no chance at recovering their lost aquifer by recharging the groundwater supply. Instead, the dead aquifer becomes a public nuisance, creating large sinkholes that can dot the area like asteroid craters. A recent study by researchers at the University of California, Riverside found that homes built in subsiding regions lost 2.4 percent to 5.8 percent of value compared to homes on more stable ground.

Last month’s study on global groundwater loss was conducted using a pair of NASA satellites collectively known as the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment, or GRACE, which Famiglietta referred to as “a scale in the sky,” because the system is designed to respond to miniscule variations in the Earth’s groundwater storage. The genesis of the new research came just after the COVID-19 pandemic, when Famiglietta was working with some colleagues who asked him to review Germany’s groundwater levels.

As he reviewed the data, Famiglietta became alarmed: There appeared to be a tipping point after a particularly strong El Niño event in 2014 caused widespread drought. The Western United States, Europe, and Central and South America all saw vastly increased drying during that period. Global dry areas are currently growing by an area roughly twice the size of California every year, even after the end of the drought.

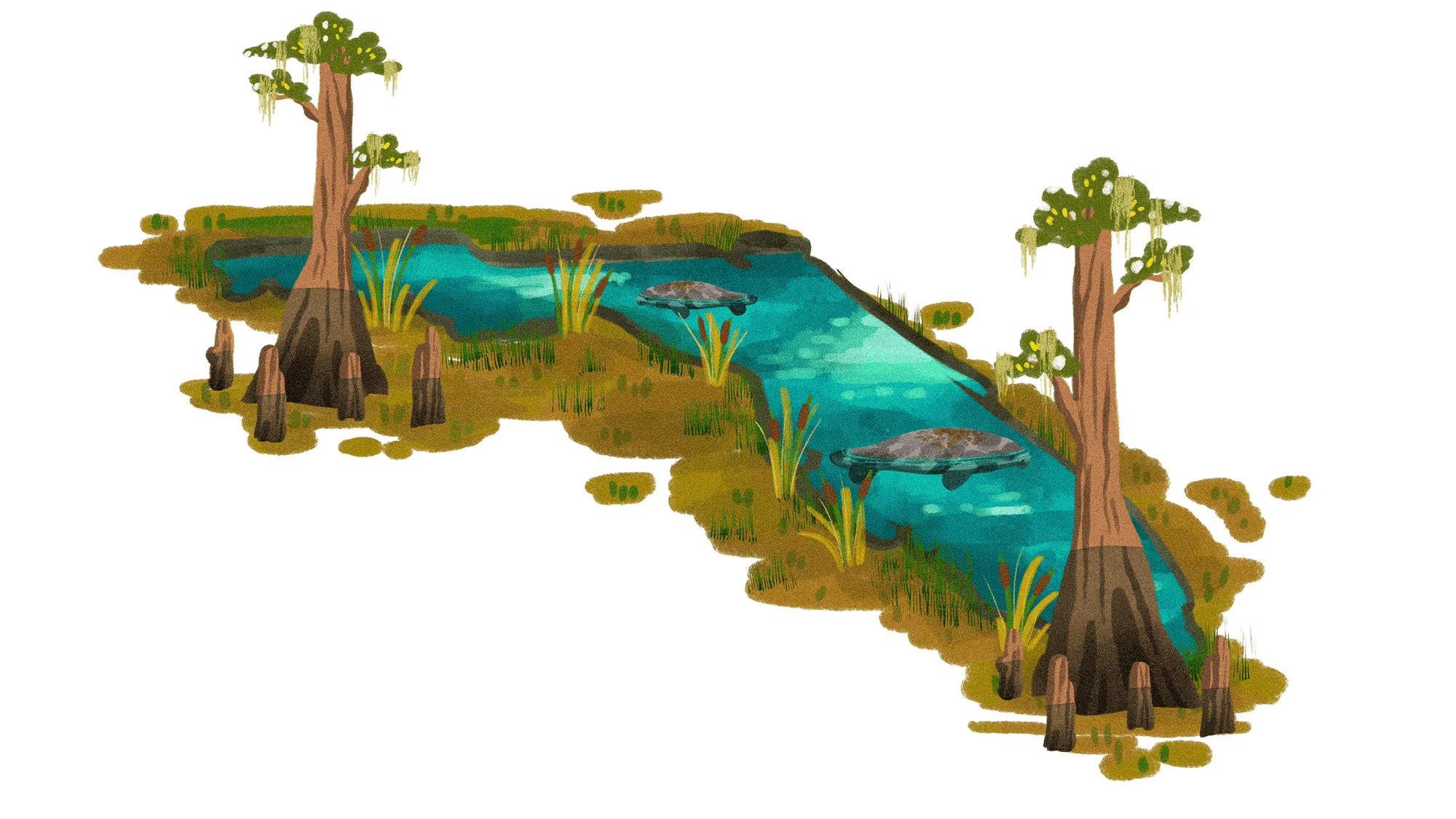

Other research shows that groundwater depletion is only part of the story: What’s left of that water, another recent study in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Geoscience shows, is heating up. Study author Susanne Benz explained that the effects of global warming have started to penetrate underground, 40 or 50 meters deep in some areas. Warming could degrade groundwater quality by increasing microbial production, and warmer water makes it easier for dangerous chemical elements usually locked safely away in rock, such as arsenic, to dissolve into drinking water. It could also upend freshwater habitats in lakes, ponds, and rivers — allowing more harmful algae blooms and killing off aquatic life.

The larger problem, Stute explained, is making it clear to people that groundwater — like oil — is a finite resource. “It will be gone. What do we do then?” he said. “In principle, we are aware of [these] issues, and we’re not doing anything.”