Last January, a series of massive wildfires broke out across the Los Angeles area, fueled by high winds and dry temperatures. The fires raged for weeks, incinerating entire neighborhoods in the wealthy Pacific Palisades and in middle-class Altadena. They killed at least 30 people and destroyed at least 10,000 homes.

As the embers cooled, thousands of displaced Angelenos scrambled to find new housing in a rental market that was already among the nation’s toughest. They scoured Zillow and Airbnb for units they could afford on short notice. What they found were sky-high prices gouged by property owners and real estate agents rushing to capitalize on the surge in demand.

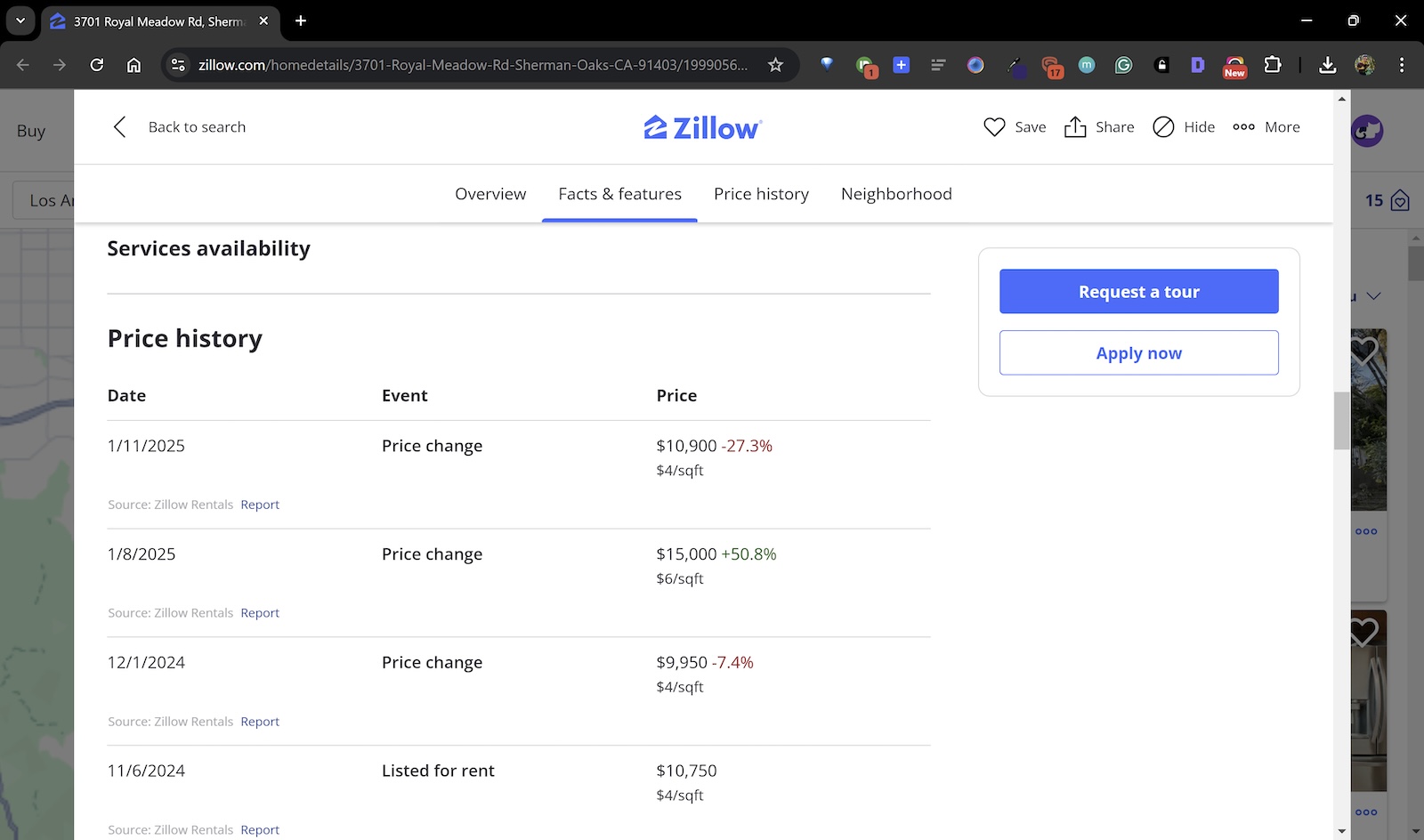

Dawn Smith and her family had rented in Altadena for nine years. After their home burned in the Eaton Fire, she combed through online listings for a similar alternative. But options were $10,000 a month or more, triple what she had been paying before the fire.

Eventually, she found a smaller place in Sherman Oaks, more than an hour away, for a still-astonishing $7,800. Her renter’s insurance would cover the difference for a few months, but not for the whole term of the lease. Now, as her insurance comes close to expiring, she and her husband are trying to figure out where to go next.

“The prices were insane,” she told Grist, “but because we had to find somewhere, we rented.”

Controversies over price-gouging play out all over the country in the wake of natural disasters as victims scramble for essential goods. Officials in New Jersey went after price-gouging gas stations after Hurricane Sandy; officials in North Carolina went after scam contractors after Hurricane Florence; and Florida prosecutors said they received more than 100 complaints after last year’s Hurricane Milton. Most states have laws that prohibit such behavior, but they are difficult to enforce in the chaos of disaster, and some economists contend that they can backfire and cause shortages or hoarding.

But housing is a special case. Overpaying for water or gasoline might be difficult, but overpaying for a rental apartment is a long-term commitment that can lead to bankruptcy or eviction down the road. Concerns about price-gouging of rental apartments have appeared after numerous recent wildfires, including the 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise and the 2021 Marshall Fire in Boulder. But prosecutors and public officials have largely failed to deter or punish this illegal behavior.

The Eaton Fire and Palisades Fires that burned large swaths of Los Angeles in January destroyed thousands of properties, displacing residents — like Ria Cousineau and her partner Emily, pictured right — into what was already one of the nation’s toughest housing markets. Frederic J. Brown / AFP via Getty Images, Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Two days after wildfires broke out in Los Angeles last January, tech founder Edward Kushins and real estate agent Willie Baronet-Israel allegedly hiked the price of a home they were renting out in the waterfront city of Hermosa Beach by 36 percent, likely an increase of more than $1,000. The city is about 15 miles from the Palisades burn zone.

A month later, California attorney general Rob Bonta sued the two, citing a state law that makes it a crime to raise prices for food and shelter during an emergency by more than 10 percent. If found guilty, Kushins and Baronet-Israel would face fines of up to $10,000 and as much as a year in prison.

But the Hermosa Beach listing was just one of thousands that were spiking in price. According to a Washington Post analysis of listings data from the firm RentCast, the average rent in the L.A. area rose by 20 percent in the two weeks after the fire — double the maximum allowable increase under California law. The home-rental company Airbnb also allowed users to raise prices above legal limits on more than 2,000 properties, despite its assurances that it would block such behavior, according to prosecutors.

The Rent Brigade

This lack of enforcement is common after disasters. But this time, it triggered an unprecedented campaign for stricter regulation of housing prices — and one that got results.

“The minimal enforcement that has happened has totally sent a signal,” said Chelsea Kirk, a tenant advocate who organized against price-gouging after the L.A. wildfires. “Landlords expect that enforcement does not exist.”

Three dozen states and the District of Columbia have laws that prohibit merchants from price-gouging during an emergency, but unlike California, which prohibits hikes of more than 10 percent, many of these laws are vague, prohibiting “excessive” or “unconscionable” increases without specifying what that means or what goods are covered.

“The laws are all over the place,” said Teresa Murray, the lead consumer advocate at the Public Interest Research Group, a nonprofit that focuses on consumer protection. Furthermore, enforcement of these laws is minimal — the government can’t be everywhere all at once after a hurricane or flood, and most disaster victims aren’t aware of their rights and don’t track or call out violators.

The stakes are even higher when it comes to housing, which is already in shortage across the country. Around half the nation’s tenants are rent-burdened, meaning they spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent. Wildfires and hurricanes often destroy thousands of homes in quick succession, exacerbating supply crunch in local housing stock.

Research from across the country shows that landlords often hike prices after major fires and floods. Asking prices for rental apartments increased by 25 percent after the 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, California, for instance, and by 44 percent in Lahaina following the 2023 Maui wildfires in Hawaiʻi. The increases even hit existing renters: More than a quarter of renters in Boulder said they saw hikes of more than 10 percent after the 2021 Marshall Fire, and a study of multiple flood events found that inexpensive apartments see hikes of 5 percent on average after a flood. These hikes hit low-income households hardest, forcing them to relocate or cut down on other expenses.

This same dynamic was on display in Los Angeles earlier this year following the Palisades and Eaton Fires. One of the people who tested this market was Blanca, a woman who lived in an apartment building in Altadena, and who declined to give her last name because of her immigration status. The Eaton Fire destroyed her business and caused significant damage to the apartment complex where she and her husband lived. Even though their unit was intact, the building lacked water, gas, and electricity.

Blanca and her husband looked for other apartments, but all the available units they found were far too expensive, some thousands of dollars above what they had paid in Altadena for the same amount of space. They couldn’t afford anything like what landlords were asking, so after a few weeks, they moved back to their unit in the damaged complex and lived there paying rent in unsafe conditions for months.

“The place has not even been inspected, and many people have returned since February,” said Blanca in Spanish. “But there was nowhere else to go.”

Are you experiencing price gouging?

In the first days after the fire, California attorney general Bonta trumpeted the state’s price-gouging ban several times — not only could landlords not raise prices by more than 10 percent, they also couldn’t list new units for more than 160 percent of typical market value. But property owners seemed either not to know about the law, or not to care.

Bonta has sent more than 750 warning letters since the fire to property owners who may have price gouged, but has initiated only four lawsuits, and so far not obtained a conviction. The city attorney of Los Angeles has filed a few of its own lawsuits, including against Airbnb, but the district attorney for much larger Los Angeles County has not filed a single price-gouging case. Legal nonprofits say they can’t pick up the slack because they need a named victim in order to sue a landlord, and most disaster victims don’t have the knowledge or resources to pursue litigation.

“We have been a little bit disappointed, I will say,” said Rodney Leggett, the director of litigation at the Housing Rights Center in Los Angeles, which has sued a few property owners over the post-fire price gouging, including the company that owns the historic Villa Carlotta apartments in Hollywood. “We have gotten complaints of people seeing price gouging, [but] we have gotten relatively few … people saying, ‘I am actively being price gouged.’ I think a big part of that is it’s really hard for people to track and to know the sort of price changes that have occurred.”

But the epidemic of price-gouging in L.A. after the fires has also triggered new progress on the difficult issue of enforcement. As Zillow flooded with overpriced homes, a group of tenant advocates began an unprecedented crowdsourcing campaign to track and shame price-gougers. Kirk, a policy advocate at the progressive nonprofit Strategic Actions for a Just Economy, was seeing numerous instances of price hikes, but she knew that Bonta’s office and local prosecutors lacked the capacity to track and sue every landlord who was posting high-priced units.

Kirk partnered with Lauren Harper, a data analyst and fellow tenant advocate, and together they took enforcement into their own hands. Forming a new organization called The Rent Brigade, they created a spreadsheet that scraped Zillow for apartment listings that violated the price-gouging laws, and also encouraged fire victims and volunteers to submit proof of gouging. In the first few weeks after the fire, volunteers submitted more than 1500 examples.

A map of reported rent-gouging across Los Angeles County in the wake of the January wildfires, courtesy of The Rent Brigade

Mike Nemeth, the head of communications for the California Apartment Association, the state’s biggest landlord lobby, told Grist that most landlords tried their best to comply with the law.

“The California Apartment Association takes seriously the legal and ethical obligations of rental housing providers during declared emergencies,” he said. “Most housing providers want to do the right thing, and our role is to help them navigate complex rules when it matters most.”

Thanks in part to the Rent Brigade’s pressure, local officials in Los Angeles are now trying to step up enforcement. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted in July to create a new system for penalizing price spike activity. Instead of waiting for a prosecutor or a legal nonprofit to file a court complaint against a landlord, the local government could slap the landlord with an administrative fine, the same way it would punish a restaurant with cockroaches in its kitchen or a driver who parked near a fire hydrant. The fines could reach up to $1,000 per day, with an additional $500 per day for failing to cooperate with county investigations.

Jamie Court, president of the advocacy firm Consumer Watchdog, said this kind of ordinance could be a model for how to enforce price-gouging laws.

“This is desperately needed as a deterrent and to let people know that price gouging is not up to prosecutorial discretion,” he told Grist. “People need to know every violation could result in a fine, not just the few prosecutors choose to prosecute.”

The Rent Brigade

Los Angeles County’s price-gouging ban lapsed at the end of July when the fire emergency ended, so the new rules will only apply the next time California declares an emergency for a fire, flood, or other calamity. But during the last months of the ban, Kirk and other advocates noticed something unexpected — and concerning. The rush of new housing demand from the fire had ended, but many landlords were still listing new units well above fair market rate.

The L.A. housing supply, Kirk and Harper concluded, was so limited that price gouging had become a normal part of the market. Even in the absence of a major shock like the fire, landlords were still asking for exorbitant rents, and tenants were still paying them. The emergency declaration had lapsed after an arbitrary period of a few months, but the overall housing picture was as bad as ever.

“When the fire started, we were seeing a lot of these units coming online for absurd prices from people who don’t usually rent, maybe knowing that people coming from the Palisades would be able to afford those kinds of things,” said Harper. “But the further that we get from the fires … I think it’s reflective of just high rents.”