When daredevil adventurers meet a tragic demise, should we mourn the way they died or celebrate the way they lived?

In May 2024, I heard news that two hypothermic, frostbitten climbers were stranded near the summit of Denali, North America’s highest mountain. I scanned the reports for detail, but rangers would not release further information other than to say that the climbers were not from the United States.

Why my interest? Because Peter, my partner of 14 years, was attempting to summit Denali at that exact same time. The summit rate at that point was a mere 15%, so even if Peter was okay, there was very little chance that he had reached the summit.

Later, I would learn that he did summit successfully. I would also learn that, on their descent, his group would stop to assist the two stranded climbers. One of those climbers – 36-year-old Malaysian Zulkifli Bin Yusof – would not survive.

Yusof was not the only casualty on Denali that year. Another climber – Japanese national T. Hagiwara – died after falling during his solo climb.

Clearly, high-altitude mountaineering is a dangerous hobby. The risk of death is real. In fact, when Peter and I were looking for a life insurance policy, we couldn’t find one that would insure him given his ambition to climb the seven summits. (Eventually, we turned to a broker who managed to assist.)

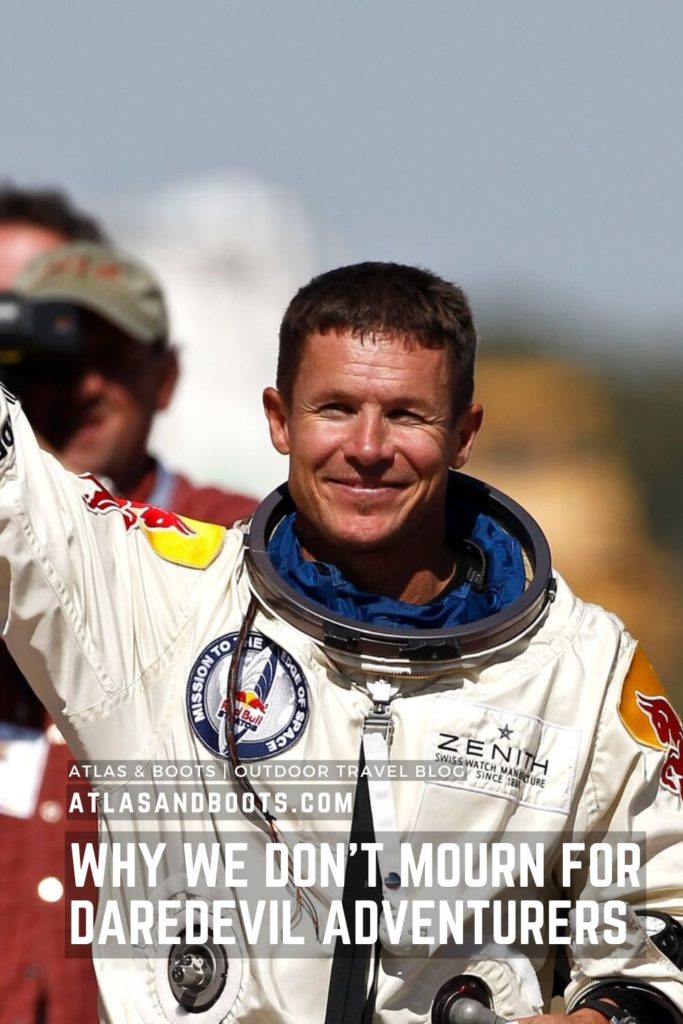

For many adventurers, the risk of death is all too real. Last month, I was startled to read the news that Felix Baumgartner had died. Baumgartner, also known as “Fearless Felix”, was most famous for his 2012 skydive from the edge of space.

The jaw-dropping stunt saw him jump from a balloon 38km (24 miles) above Earth. During his nine-minute descent, he became the first skydiver to break the sound barrier, reaching a peak speed of over 1,343km/h (834mph).

Baumgartner died at the age 56 during a paragliding incident in Italy. As a pioneer of extreme sports, clearly he understood the risks involved. He would know well that if you court death, sometimes death will answer you. With this in mind, should we civilians mourn daredevil adventurers like him?

Another example is Ueli Steck, famous for his rapid ascent of the Alps. In 2017, at just 40 years old, he fell to his death on Mount Nuptse in the Himalayas. I first came across Steck in the documentary Sherpa and came to learn why he was regarded as one of the best climbers of his generation. He too courted death. And he too was taken.

There are myriad other examples. Natalia Molchanova on a free dive, Alison Hargreaves on K2, Pavel Kashin while freerunning. Base jumpers die regularly. In the last few months alone, I’ve read about the deaths of Liam Byrne, 24, Dylan Roberts, 32, James Nowland, 42, and Carlos Suarez, 52.

This ‘tradition’ stretches back in time. Amundsen, Earhart, Mallory, Scott. The list goes on – and will go on. I fear that, one day, we’ll hear of the premature deaths of Nims Dai or Alex Honnold, or similarly fearless daredevil adventurers.

Many say that these daredevil adventurers deserve none of our sympathy – but this often comes from a place of cynicism. Pale, stale, male columnists will loudly decry the “macho idiots” who want to climb high mountains. They will shout “Close Everest! Close all the damn mountains!” couching their objections as concern for the environment, or Sherpas, or anything that gives them the moral high ground.

In reality, a good proportion of criticism comes from a place of jealousy, I believe. So many of the loudest critics have led prosaic, uncourageous lives. Some of them had their biggest achievements handed to them on a plate (naming no names, G*les C*ren). To me, it seems that these critics minimise, criticise and castigate others as a way to elevate themselves.

Personally, I don’t mourn for these daredevil adventurers for one simple reason: they died as they lived: bravely, fearlessly, with more guts than most of us will ever have. They looked into the great unknown and thought, “Yeah, I’ll go see what that’s about.”

Mark Twain once wrote that, “20 years from now you will be more disappointed by the things that you didn’t do than by the ones you did do. So, throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover.”

Many of these adventurers never got an extra 20 years, but they did explore and dream and discover. That is why we don’t mourn the way they died but celebrate the way they lived.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…