A trip on the Amazon is almost the definition of Adventure Travel: hiking to suspension bridges, riding in a dugout canoe, fishing for piranha, swimming in the river, and spotting monkeys, sloths, and dozens of bird species.

When I set out on a riverboat adventure in Peru, I found an experience that was surprising but also easier than I expected. Traveling with G Adventures on their Amazon Riverboat Adventure in Depth, I spent nine days immersed in biodiversity, local culture, and river life. It was a trip that surprised me at every turn: from watching pink dolphins surface to meeting a village shaman.

This wasn’t a luxury cruise, nor was it meant to be. Instead, it was a small-group expedition with about two dozen fellow travelers, a riverboat that became our floating home, and two naturalists whose passion for the region made every outing fascinating. If you’re thinking of an Amazon cruise, let me take you along on mine.

“Michael Jackson monkey”

Table of contents: ()

Getting Started: Lima to Iquitos

Our journey began in Lima, where G Adventures gathered the group at a hotel in the Miraflores district. We had a short briefing the first night, including some practical advice like don’t drink the tap water, avoid hailing cabs on the street, and use ATMs for cash.

The next morning, we were off to the airport. A flight brought us to Iquitos, one of the world’s most isolated cities. You can’t reach it by road; only by air or river. Iquitos itself is a city of nearly half a million people, and yet it feels like it could be the end of the earth. It is surrounded by rainforest and connected only by the Amazon and its tributaries, especially the Marañón River and the Ucayali River where we would spend most of our time.

From there, we drove the only highway out of the city, just 97 kilometers, to a small port town called Nauta. This highway is the only road leading out of Iquitos, and it ends at the river. Beyond that, the only way to travel is by water. It is a highway filled mostly with motocarros, a Peruvian version of a tuk-tuk, half motorcycle and half rickshaw.

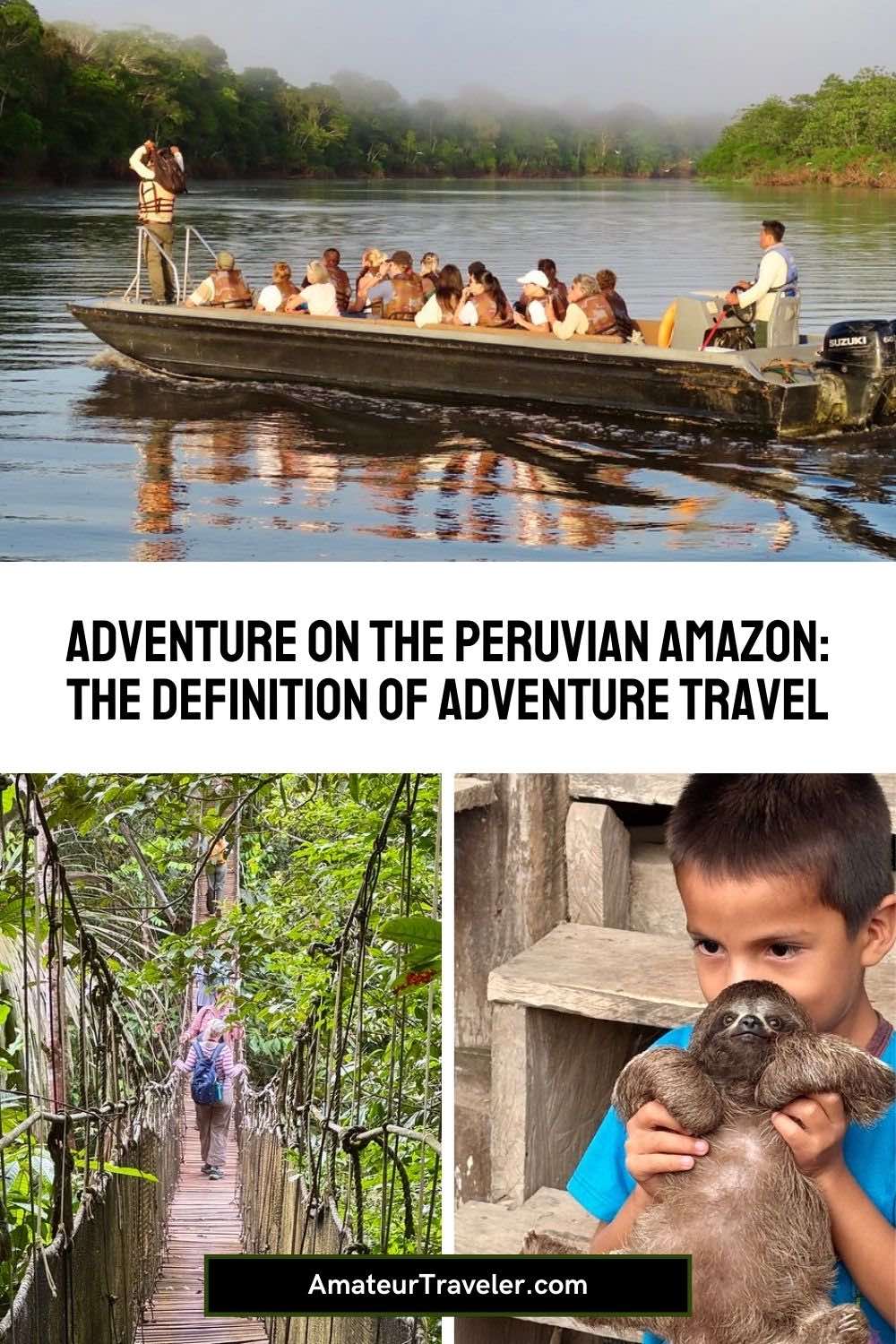

We boarded skiffs, long, sturdy boats with outboard motors, that ferried us to our home for the week, the Amatista.

The Ever-Changing Amazon

One of the first lessons I learned is that the Amazon is never the same trip twice. The water levels change dramatically between the high-water and low-water seasons, up to 30 feet in some areas. When we visited in late July, the waters were receding. Every village visit was a bit of an adventure as we were greeted with often rickety stairs and muddy banks. Stairs had to be rebuilt constantly as the shoreline shifted. They were a challenge to those with mobility issues.

This seasonal rise and fall affects everything: when you can fish, the houses built on stilts, the crops villagers can plant, and even which tributaries are navigable. Our guides adjusted our daily excursions based on the river’s condition. Every day felt like a unique discovery. Rivers that were open to our skiffs one week might be impassable the next. Our guides would point to high water marks on tree trunks ten feet above our heads, evidence of how high the river had been just months before.

And this isn’t just a minor fluctuation. Imagine whole reserves, millions of acres, submerged for months at a time. We spent much of our time in the huge Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve. This park is half the size of the country of Costa Rica. During high water, 95 percent of the Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve is underwater.

Terrestrial animals are forced to crowd into the 5 percent of land that remains dry, while fish and dolphins spread into the flooded forests. By the time we visited, the water had already dropped around 18 feet or six meters, and it would fall even more before the low-water season reached its peak.

Life on the Riverboat

The Amatista has three decks and accommodations for just over two dozen passengers. My cabin was simple and small but comfortable, with just enough quirks, like a sloping floor and the challenge of hot water, to remind me that this was no five-star hotel. But what it lacked in polish, it made up for in charm.

Meals were served buffet-style, hearty and plentiful, with a mix of Peruvian dishes and international fare. Breakfasts always included fresh fruit and eggs, something like pancakes, along with coffee, tea, and juice. Lunches and dinners featured soups, salads, rice, potatoes, and usually meat and fish. One night, we sampled Peruvian takes on Chinese dishes, a reminder of the cultural melting pot that makes up Peru’s cuisine. Each evening, there was some new creative table setting, like a woven fron in a green napkin, a lily pad.

The real highlight, though, was the top deck: an open-air lounge shaded from the sun. It became our social hub, where we traded stories and photos, sipped pisco sours, and watched the river slide past. From dawn mists to evening sunsets, this was where the Amazon revealed its moods. Some mornings, I would rise early just to watch the fog lift off the water as dolphins surfaced nearby and the jungle came alive with sound.

Evenings often brought unexpected entertainment. Three nights, members of the crew, joined by our guides, formed a makeshift band. Three of the musicians were professionals who normally performed on the streets of Iquitos. Their talent was undeniable. We clapped and danced along to guitars, percussion, and voices.

Daily Rhythm on the River

Our days quickly settled into a pattern. We would wake around dawn, often with mist still hanging over the river. Early morning skiff rides were prime time for spotting birds and monkeys as they stirred in the canopy. Later, there might be a village visit or a longer expedition up a tributary. Afternoons were quieter, sometimes with lectures about local ecology or history, followed by another outing before or after dinner.

That rhythm of exploring, learning, and resting created a balance that made the trip both active and relaxing. On some days, we went out three separate times, once in the morning, once in the afternoon, and again at night. Other days included longer excursions, like a jungle hike or a visit to a market.

Wildlife Encounters

If you come to the Amazon for wildlife, you won’t be disappointed. Every skiff ride revealed new creatures. On the very first outing, we saw sloths, their shaggy forms barely distinguishable from the branches they clung to. We also spotted spider monkeys, always in motion and seldom willing to pose for photos.

Young Black Caracara

Birds were everywhere: egrets, herons, vultures, and the loud horned screamer, sometimes called the “donkey bird” for its braying call. My favorite might have been the black-capped donacobius, also known as the “car alarm bird,” which sounded exactly like a car alarm gone off in the jungle.

Later in the week, we saw the Michael Jackson monkey, also known as the monk saki, for its distinctive white hands. We spotted troops of squirrel monkeys leaping through branches in the late afternoon light, and once we even saw the smallest monkey of all, the pygmy marmoset, no larger than a human hand. Our guides found it by sound alone, a high-pitched call that most of us would have missed.

And then there were the dolphins. Both gray and pink river dolphins live in the Amazon, and we saw them nearly every day. The gray dolphins leapt from the water, while the pink dolphins surfaced more quietly with a puff from their blowholes. They were mesmerizing. Seeing their curved backs break the surface, often right near the boat, never got old.

fish hawk

Bird lovers would have been in heaven. At one point, one of our naturalists told us that more than 370 bird species could be spotted in the reserve in just a week. We didn’t see that many, but it felt like we were constantly spotting something new: wood storks, kingfishers, boat-billed herons, macaws, toucans, hawks, vultures, and countless smaller species. Each had a story, from the vulture that dries its wings because it lacks oil glands, to the macaws that mate for life and can live a century.

Not every animal encounter was cuddly. Night excursions revealed caimans lurking along the riverbanks, cane toads with bulging eyes, and fishing bats skimming the water’s surface with 16-inch wingspans. We saw bats roosting against tree trunks and falcons waiting nearby to prey on them. On land, we heard stories of venomous snakes like the fer-de-lance. Thankfully, none made an appearance.

Photography

For photographers, the Amazon is both heaven and a challenge. Many birds perch far above in the canopy, requiring long zoom lenses or binoculars. Lighting shifts quickly under the dense foliage. I shot hundreds of photos and deleted most, but the few sharp captures of macaws in flight or sloths in treetops made the effort worthwhile. Binoculars were just as essential, allowing me to watch monkeys scramble high above or to admire the delicate colors of a distant bird.

Learning from the Naturalists

Two guides accompanied us throughout the week: Victor and Erik. Their passion and deep knowledge brought the jungle to life. They could identify birds from their calls before we even saw them, explain the significance of plants that seemed ordinary, and tell stories that connected the ecology with human history.

Victor, in particular, had an infectious enthusiasm despite 20 years of guiding. He would get as excited as any first-time visitor when spotting a rare bird, urging us to take a photo. Erik’s lectures on biodiversity and climate gave context to what we were seeing, reminding us that Peru contains more than half the world’s microclimates and some of its most vital ecosystems. They spoke about the Amazon’s cycles of flooding and drying, and about the resilience of both people and animals in adapting to such dramatic changes.

One of the most fascinating aspects of traveling with naturalists was how they heard the forest. They could distinguish between dozens of calls: the chatter of monkeys, the croak of a frog, the shriek of a bird. To me, it was an indecipherable chorus; to them, it was a language that told them exactly where to look.

Village Visits

Our cruise wasn’t only about nature. We also visited villages along the river, meeting the people who call this region home. In one community of about 120 residents, we learned about their projects: raising stingless bees for honey and cultivating butterflies for conservation. Children greeted us with pet canaries and, in one unforgettable moment, a baby sloth. While keeping sloths as pets isn’t encouraged, it was undeniably adorable.

The homes stood on stilts to withstand seasonal floods, with palm thatch or tin roofs. We saw solar panels, rainwater collection, and even a small water purification system built by Engineers Without Borders. Life here is simple, but full of resilience and ingenuity. Families plant crops like rice, yucca, and corn on the fertile sandbars when the water recedes, knowing they will be flooded again in a few months. Chickens clucked under stilted houses. The rhythm of life here is tied directly to the river’s pulse.

In conversations with locals, we learned about the challenges they face: unpredictable floods, limited access to health care, and the difficulty of keeping traditional languages and culture alive in a rapidly globalizing world. Tourism plays a small but important role.

Handicrafts were offered at the end of our visits, including woven palm animals, jewelry, and other souvenirs. These purchases were more than mementos; they were a way to contribute, however modestly, to the communities we had visited.

Markets and River Life

In the port town of Nauta, we wandered through a bustling market. Here, little goes to waste: chickens were sold by every part, fish were salted for preservation, and vegetables and grains filled the stalls. The smells of fresh herbs mingled with those of drying fish. People were buying food for the day. For many, the day they work is the day they eat.

The market also told the story of adaptation. During the dry season, when fishing is easier, people preserve fish by salting them, ensuring they’ll have food when the waters rise again and fishing becomes difficult. In the meat hall, nothing was wasted. Offal that might be discarded elsewhere was carefully set aside to be used. This was a market where survival shaped every transaction.

Outside, we rode in moto-carros, three-wheeled motorcycle taxis that buzzed like colorful beetles through the streets. We also saw locally made wooden buses carrying people and goods.

We glimpsed giant arapaima fish in a lagoon in Nauta, ancient creatures that breathe air and can grow up to 10 feet long. They surfaced every few minutes with a gulp of air, a reminder of how unique Amazonian species can be. Their presence felt almost prehistoric, as though we were peering back into another age.

A swim in the river – photo by Jennifer Slinn

A Swim in the Amazon

One of the boldest activities of the week was swimming in a “blackwater” river. The water, stained the color of tea from tannins from plants, was opaque and mysterious. Our guides assured us it was safe, with too little oxygen for piranhas, for instance, to thrive. Still, jumping into water where you can’t see what shares it with you requires a leap of faith. The coolness was refreshing, and climbing back into the skiff, we felt exhilarated.

It was a reminder that sometimes travel requires stepping outside your comfort zone. I’ll admit, I hesitated on the edge of the boat, wondering what lurked beneath. But once I climbed in, I realized this was exactly why I had come: to experience the Amazon not just as a spectator, but as a participant.

Meeting a Shaman

Midway through the cruise, we visited a shaman, a woman who had trained for years in solitude to learn the healing plants of the jungle. She welcomed us with ritual smoke, spoke of curing ailments with leaves and roots, and shared her journey. While some cures involved spiritual beliefs, others were firmly rooted in jungle pharmacology. Our guide Victor credited her with saving his life when modern medicine had failed.

She described how she had been chosen during an ayahuasca ceremony, then spent eight years living alone in the jungle, learning about plants from her grandfather. Today, she treats locals with a mix of herbal medicine and spiritual guidance.

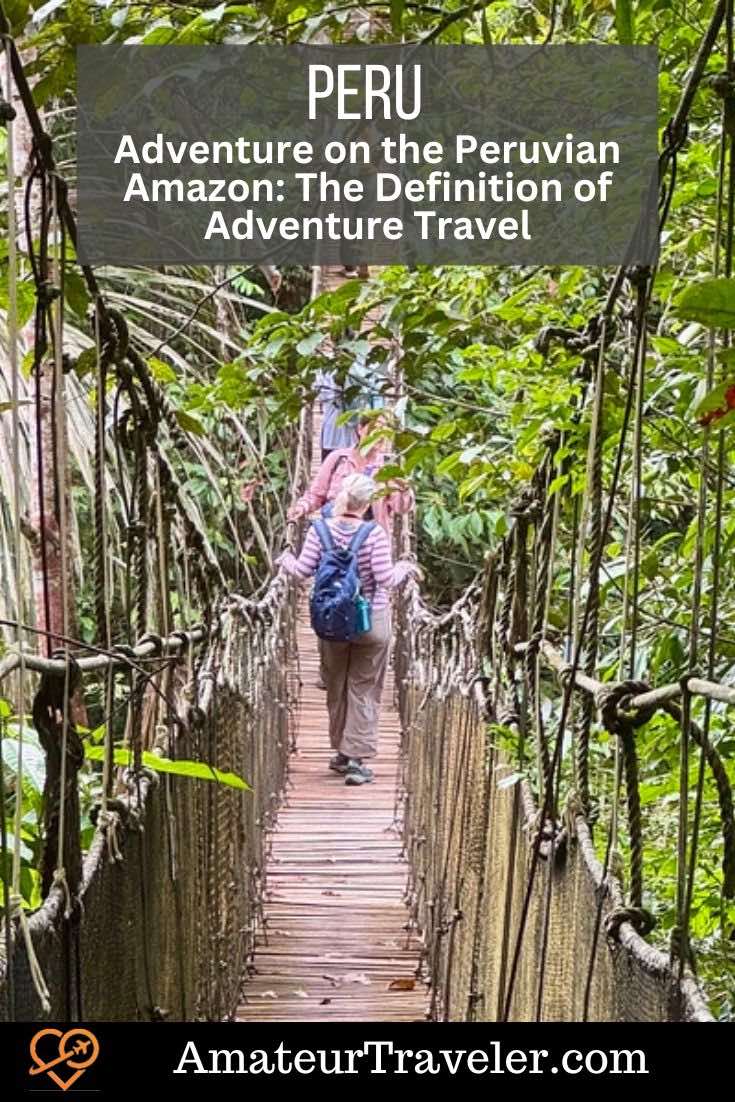

Jungle Walks and Suspension Bridges

For all the boat outings, one of the hardest adventures was on foot: the first jungle walk on terra firma, the dry land that makes up just 5% of this region. We hiked about a mile uphill from the river to reach a series of suspension bridges. There are normally eight of them, but a lightning strike had damaged part of the system, so only four were open when we visited. These were not lofty canopy walkways; instead, they were simple wooden suspension bridges that swayed and creaked as we crossed. The planks creaked a little with each step, adding a thrill to the experience.

The trail itself was muddy, more terra than firma, and I was glad for the loaner rubber boots provided on the boat. The humidity was intense, and I quickly wished for more DEET and a second water bottle.

This first jungle hike was rich in discoveries. We walked past towering kapok trees and even saw a rare mahogany tree growing near the shore. Some of the trees had wide buttress roots. We learned about a white fungus-infected tree that would glow faintly at night, creating an eerie light in the forest.

We saw giant philodendron trees. Our guide told us that bullet ants eat philodendron seeds. The seed germinates inside the ant, ultimately killing it, the stuff of nightmares. Wildlife encounters included hearing tamarin monkeys in the canopy, spotting a bullfrog, and seeing a tapped rubber tree. Most memorably, we came across a giant tarantula the size of my hand, crouched on the forest floor.

In a nearby web, we also found social spiders that shared one large communal nest. The combination of heat, humidity, and wildlife made the walk a challenge, but also one of the most vivid memories of the trip.

The second jungle walk later in the week was shorter and easier but equally fascinating. This time, the focus was on medicinal plants: ficus trees used to fight parasites, a candlestick flower in the ginger family for high fevers, and spiny trees whose bark could serve as natural graters. We saw palm fibers used for weaving and a curare tree, once infamous as the source of poison for darts used in hunting or warfare. Today, curare derivatives are used in modern medicine as anti-venoms and muscle relaxants.

Wildlife on this hike included tamarin monkeys, a dead-leaf toad, bats roosting in a hollow tree, and even a massive anaconda coiled among the roots. The snake made a mock strike in our direction, reminding us that the jungle always holds surprises. Together, these two walks gave us a deeper appreciation for the rainforest: one for its scale and challenges, the other for its medicinal secrets and hidden dangers.

Pirahna Fishing

One afternoon, we tried our hand at piranha fishing, an activity that carried equal parts excitement and apprehension. The crew handed us simple poles with a bit of line and a hook baited with small scraps of meat. We stirred the water, then dropped our hooks into the murky, tea-colored water and waited only moments before feeling sharp, sudden tugs. The piranhas struck quickly, sometimes stealing the bait clean off the hook before we could react. With a bit of persistence, though, most of us (but not me) hauled them up into the skiff.

The fish themselves were not the largest piranha we were told, but their mouths told the real story. Rows of triangular teeth gleamed in the sun. Holding one up for a closer look required care. For us, it was a thrilling diversion and a chance to test jungle lore, but for the communities along the river, piranha fishing is a practical way to supplement their diet.

Reflections on Comfort and Challenge

Before the trip, I worried about heat, humidity, and mosquitoes. In reality, conditions were easier than I expected. Breezes on the river kept the temperature tolerable, and while mosquitoes were present, long sleeves and repellent kept them at bay. The cabins were modest but comfortable. This was adventure travel, not hardship.

What struck me most was the balance: the Amazon challenged me with mud, mystery, and occasional discomfort, yet offered rewards far greater than the effort. Watching a dolphin break the surface, hearing the jungle chorus at night, or sharing a laugh with a local child, these moments outweighed every mosquito bite.

Travel Companions

My companions were a diverse group. There were about two dozen of us in total, including a 90-year-old grandmother, two of her daughters, and two of her granddaughters. Some were solo travelers, others came as couples or families. By my count, there was a family of 3 from Peru, 3 from Australia, 4 from England, 4 from Canada, 2 from Germany, 1 from China, and the rest from the United States.

Over meals, on skiff rides, or during quiet evenings on the top deck, conversations wove together stories from different lives. Some travelers were adding Machu Picchu or Cusco to their itineraries, while others, like me, had come solely for the Amazon. What united us all was a shared curiosity and willingness to embrace adventure. By midweek, we were no longer strangers but companions, pointing out wildlife to each other, cheering on hesitant swimmers in the blackwater river, sharing jokes, and dancing as the crew band played.

Practical Tips for an Amazon Cruise

- When to go: Water levels change the experience. High water means you’ll float into flooded forests; low water means more land excursions. July–August offered us good wildlife sightings and manageable weather.

- What to pack: Lightweight long sleeves and pants (for bugs and sun), a hat, sturdy shoes, and a rain jacket. Binoculars and a good zoom camera are essential for wildlife.

- Health precautions: Check vaccination requirements. Anti-malarials may be prescribed, though our guides said malaria isn’t endemic where we traveled. Insect repellent is a must.

- Comfort level: Expect rustic charm, not luxury. The boat is comfortable, but quirks come with the territory.

- Mindset: A sense of adventure is required. Be ready for mud, mosquitoes, and surprises, but also for unforgettable rewards.

Conclusion

The Peruvian Amazon was unlike anywhere I’ve traveled. It challenged my expectations: less hot, less buggy, but far more vibrant than I imagined. It wasn’t just the wildlife, the dolphins, monkeys, and birds, but the people, the villages, and the rhythm of the river that made the experience so rich.

To hear more, listen to Cruising the Peruvian Amazon with G Adventures – Amateur Traveler Episode 957