Leveraged loan market and CLOs

For these companies this is helpful as it gives them alternative access to capital. Problem is that some of them use the money from such loans to buy back stocks or pay out dividends, thus presenting a better image of themselves to their shareholders. The obvious negative consequence is piling up more and more corporate debt, making such loans even more risky and with a greater probability of default.

All this is creating a systemic imbalance in the economy. If companies are using debt to buy back their stocks, or are simply exploiting the low interest rate environment, an economic downturn could severely impact their earnings. This will make it even more difficult to service those debts which would significantly increase the threat of bankruptcy, and by extension increase the risks for banks.

|

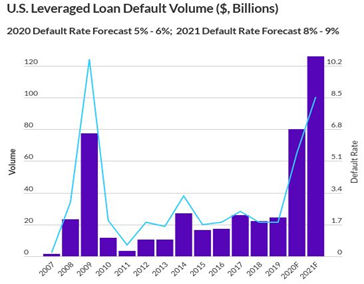

| Expected leveraged loan defaults according to Fitch. |

Risk sources in the leveraged loans market

There are several sources of risk for banks in the leveraged loans market. Frist there is exposure to revolving credit facilities and warehouse facilities – short-term funding for firms with liquidity problems – of around $780 billion. Second there is exposure through the arrangement of syndicated loans where banks are at risk of keeping more shares than they wanted through pipeline exposure if investors for some reason do not pursue with investment as agreed. US banks have an exposure of around US$65 billion through this mechanism. Finally, there is exposure through third party CLOs, the market for which is over $700 billion (3.27% of GDP), where the cumulative losses of the top three US banks would be around $40 billion in the worst-case scenario of massive corporate bankruptcies.

The biggest defaults on leveraged loans are expected in sectors with highest sensitivity to the pandemic: energy, non-food retail, restaurants, travel/leisure. Total volume of high-risk sectors accounts for approximately $225 billion or 16% of the leveraged loans market. By the end of 2021 defaults could go up to $200 billion, while defaults of leveraged loans will top $80 billion in 2020 and $120 billion in 2021 which is in both cases higher than the previous record of $78 billion defaults in 2009, however the default rate is projected to be slightly below the 10.2% in 2009 (as shown in the figure below). Higher expected defaults of such loans could destabilize banks holding large volumes of CLOs.

|

| Distribution of US corporate debt by rating category. Source: Fitch. |

Investment grade bond issuance and holders

In the overall corporate debt market about $8 trillion are corporate bonds. The majority (72%) of rated corporate bonds in the US are investment grade (>BB). That being said, and the fact that so far in 2020 issuance of investment grade corporate debt has reached $1 trillion, a closer attention needs to be payed to the investment grade itself.

The majority, around 54%, of investment grade debt is rated BBB or Baa (Moody’s) and it is clear to see how the number of issuers is disproportionally lower in comparison to the amount issued (see figure above). This implies higher risk of defaulting because amounts borrowed are concentrated between a smaller number of borrowers. If BBB rated debt gets downgraded (and as of June 20th 20% of BBB is on negative outlook in comparison to 6% at the beginning of the year), it automatically becomes “junk”. These downgraded bonds alone have added $88 billion of supply to the high-yield bond market so far this year. This is particularly important in the current pandemic where a company’s ability to return the borrowed money becomes less probable and a downgrade in ratings becomes a possibility.

Given that this debt is being used as a tool for refinancing, M&As, and leveraged buyouts (especially in March, April and May 2020), which does not necessarily lead to a prosperous future of the company, pilling up debt in still uncertain times of COVID-19 is not a sound business strategy.

Furthermore, structurally higher non-financial corporate leverage has a procyclical effect on debt and equity prices of publicly listed corporates and, as such, can amplify financial market shocks. In other words, companies increasing leverage now as a consequence of the COVID pandemic, are becoming even more vulnerable and increasing their risks of bankruptcy.

Historically, investment-grade bonds witness a low default rate compared to non-investment grade bonds. However, if the downgrades persist certain holders like life insurances, where the industry has increased its exposure in this class by about 75% over the past 10 years, could be urged to boost their capital buffers because the risk-weighted ratio would be changed.

Expecting downgrades, bankruptcies, and deleveraging

In conclusion, the US leveraged loans market will almost certainly continue to grow. The biggest holders of those loans have stable protective buffers, while the amounts invested in leveraged loans in relative terms (in comparison to total assets) are not considered as a major default threat yet.

On the other hand, the recent growth of BBB-rated corporate bonds poses much more concern. The majority of corporate debt invested in BBB-rated debt is by its structure one step away from getting downgraded to “junk” status which could then cause a chain reaction of investors selling those bonds, followed by a further bond price deterioration and overall financial instability. A downgrade does not immediately imply default but non-investment grade debt historically had bigger chances of defaulting. Furthermore, the systemic downturn also depends on investors’ willingness to hold downgraded bonds and on other investors taking advantage and buying recently downgraded bonds.

The situation and predictions in the corporate bond market change on a weekly basis as more bonds get downgraded, more companies default and the COVID-19 uncertainties are still present. Therefore, to be able to make clearer conclusions, the reevaluations and analyses of the corporate bond market need to be followed constantly in the next few months.

One thing is certain, with such huge debt levels one can expect large deleveraging from the private sector, which is likely to mirror potential austerity measures of governments in the years to come.