The “Chat Control” law threatens to transform the Internet into an even more centrally controlled, surveilled environment. And it could be a legal reality by October.

Regular readers are by now familiar with the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA), which we have covered on several occasions since July 2023. For those who aren’t, a quick primer: the DSA imposes a legal requirement on very large online platforms (VLOPs), and very large online search engines (VLOSEs) to take prompt action against illegal content hosted on their platforms, either by removing it, blocking it, or providing certain information to the authorities concerned.

VLOPs and VLOSEs are also required to take action against risks that extend beyond illegal content, including vague threats to “civic discourse”, “electoral processes” and “public health”. It is down to the Commission or national authorities to define what those threats might entail. This is where the EU’s mass censorship regime began to take form.

The overarching goal of the DSA is to combat — i.e., suppress — mis- and disinformation online, not just in Europe but potentially across the world. It is part of a broader trend of Western governments and UN institutions pushing to censor information on the Internet as they gradually lose control over key narrative threads.

Platforms that fall foul of the Act face potentially ruinous fines of up to 6% of their global annual turnover. As such, it’s probably safe to assume that they err on the side of caution, deleting content that could be considered harmful, even when it is entirely lawful. So begins the slippery slope of systemic online censorship.

As retired German judge Manfred Kölsch warned in an op-ed in Berliner Zeitung, the DSA not only poses an existential threat to the freedom of speech in Europe, it contravenes many of the EU’s own laws on freedom of expression and information:

A careful look behind the facade of the rule of law reveals that the DSA knowingly undermines the right to freedom of expression and information guaranteed by Article 11 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Article 5 of the Basic Law (Germany’s written constitution, agreed by the allies back in 1949 when the first post-war government was established in West Germany).

The text of Article 11 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights reads as follows:

Everyone has the right to freedom of expression. This right shall include freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart information and ideas without interference by public authority and regardless of frontiers.

As we warned back in 2023, the reverberations of the DSA are likely to extend far beyond the EU’s borders and could even go global, much like its predecessor, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Those concerns were echoed by a report released in January by the US House of Representatives Judiciary Committee, which singled out the DSA as a “foreign censorship threat.” From Politico:

[The report] includes non-public information about how the European Commission and national authorities implement the rules, including confidential information from EU workshops, emails between the EU executive and companies, content takedown requests in France, Germany and Poland and readouts from Commission meetings with tech firms.

“On paper, the DSA is bad. In practice, it is even worse,” the report said.

“European censors” at the Commission and EU countries “target core political speech that is neither harmful nor illegal, attempting to stifle debate on topics such as immigration and the environment,” it said. Their censorship is “largely one-sided” against conservatives, it added.

This assertion is supported by recent claims from Telegram founder Pavel Durov that French intelligence officials approached him earlier this year with requests to censor pro-conservative content ahead of the May 2025 Romanian election, a request he says he refused. As Le Monde notes, Durov hasn’t provided any evidence to support these claims. However, given the lengths to which the EU went to meddle in the Romanian election, they are hardly far-fetched.

Interestingly, diplomatic wrangling over the DSA’s wording is one of a number of ongoing issues holding up a trade statement formalising last month’s trade deal the EU and US. According to the FT, the EU is trying to prevent the US from targeting the bloc’s landmark digital rules as the two sides wrangle over the final details of a delayed statement:

EU officials said disagreements over language relating to “non-tariff barriers” — which the US has previously said includes the bloc’s ambitious digital rules — are among reasons for the hold-up of the joint statement.

It was originally expected days after European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen and US President Donald Trump announced a tariff agreement on July 27 in Scotland. Two EU officials said the US wanted to keep the door open for possible concessions on the bloc’s Digital Services Act, which forces Big Tech companies to police their platforms more aggressively. The commission has said that relaxing these rules is a red line.

Chat Control

In the meantime, Brussels is pushing hard on another front: its so-called Regulation to Prevent and Combat Child Sexual Abuse. Dubbed the “Chat Control” law, the proposal seeks to curb the spread of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) online. While this is a commendable goal, the way the EU is going about it not only threatens fundamental rights and protections for everyone; it risks transforming the Internet into an even more centrally controlled, surveilled environment.

In its current form, the Chat Control law effectively mandates the scanning of private communications, including those currently protected by end-to-end encryption. If enacted, messaging platforms, including WhatsApp, Signal and Telegram, would have to scan every message, photo and video sent by users, even when encrypted, starting in October.

As Brussels Signal notes, the mechanism at the heart of the proposal is called client-side scanning, and Denmark’s rotating six-month presidency of the EU council is determined to push it through — indeed the resubmission of the Chat Control legislation, first proposed in 2022, was the presidency’s very first formal step upon its assumption of duties in July:

Through [client-side scanning], content is analysed on a user’s device before encryption. What this means, for the less tech-savvy reader, is opening a permanent backdoor that bypasses the privacy guarantees of secure communication. This would be like having the state read your letters before you seal the envelope, and would subject every EU citizen’s private messages to automated scrutiny. East German readers may find such Stasiesque instruments familiar; most wouldn’t want them making a grand comeback, either in Germany or elsewhere.

Unfortunately, instead of reading the room and studying alternative, milder versions of the legislation, (Danish prime minister Mette) Frederiksen has instead chosen to double down on this major political and historical mistake. As many as 19 EU states now apparently back the proposal. Germany remains uncommitted for the moment, but will likely be pivotal. Indeed, if Berlin joins the “yes” camp, a qualified majority vote—requiring 15 states representing 65 per cent of the EU population—could see the law passed by mid-October. The Danish presidency is driving this process through Council working groups, with its objective being to finalise positions by September 12, 2025. The only step that would then be missing is the final vote in October.

The downsides of the EU’s Chat Control are self-obvious, notes the Brussels Signal article, and should suffice to prompt a sound rejection by European nations, which obviously isn’t happening:

Once it is in place, the system’s scope could expand beyond CSAM to virtually any other content, be it political dissent—surely a reasonable concern when, in Britain, Starmer is hard at work forbidding your VPN, France’s leading presidential candidate was barred from running in the next election or, in Germany, almost 10,000 are being charged every year for sharing “politically incorrect” memes and jokes online. Indeed, even as the Eurocrats are trying to snoop into your online conversations, Brussels is also pushing for aggressive content moderation under the Digital Services Act.

So the downsides are self-obvious, and should by themselves illustrate why this legislation should be soundly rejected by European nations. How about its advantages? They’re way less clear. A year ago, Europol noted in a report that sophisticated criminals often use secretive, unregulated platforms, rendering mass scanning ineffective against the intended targets while burdening ordinary citizens with the full weight of a repressive Leviathan. Confidentiality-focused platforms like Signal have threatened to exit the EU market rather than comply. So they should, but what that will do is harm Europe’s digital economy while pushing users to less secure alternatives.

The EU’s “Chat Control” proposal is horrifying. There’s no way to implement this safely. It will destroy private communications online entirely.

If you’re in the EU, please fight this. pic.twitter.com/VVQtdC6p6e

— Theo – t3.gg (@theo) August 11, 2025

The UK’s experience so far with the Online Safety Act’s age verification rules offers a foretaste of how much chaos can by generated by government crackdowns on online access and speech. One of the most notable impacts so far has been a proliferation of work-arounds, including VPNs and other inventive ways of bypassing age verification systems.

As the Keir Starmer government is slowly learning, trying to restrict people’s access to the Internet is a game of whack-a-mole — and one that the government appears destined to lose. In the meantime, the OSA appears to have sparked a new wave of mass civil disobedience, particularly among young, tech-savvy users:

This is what happens when Western authoritarians attempt to assert regulatory, centralised dominance with ‘protect the children’ ™

You cannot age verify & control the entire internet. https://t.co/63aIM29OjK

— STOPCOMMONPASS 🛑 (@org_scp) August 17, 2025

“A Masterclass of Unintended Consequences”

As the Centre for European Policy Analysis notes, the unintended consequences are rapidly mounting:

By sending minors tunnelling through VPNs, the UK law may have inadvertently exposed them to riskier, less regulated online spaces. Many free VPN services are not privacy shields at all, but data harvesting tools that sell users’ information to unknown operators overseas. In trying to wall-off harmful content, governments may be nudging minors into darker, less-regulated corners of the internet.

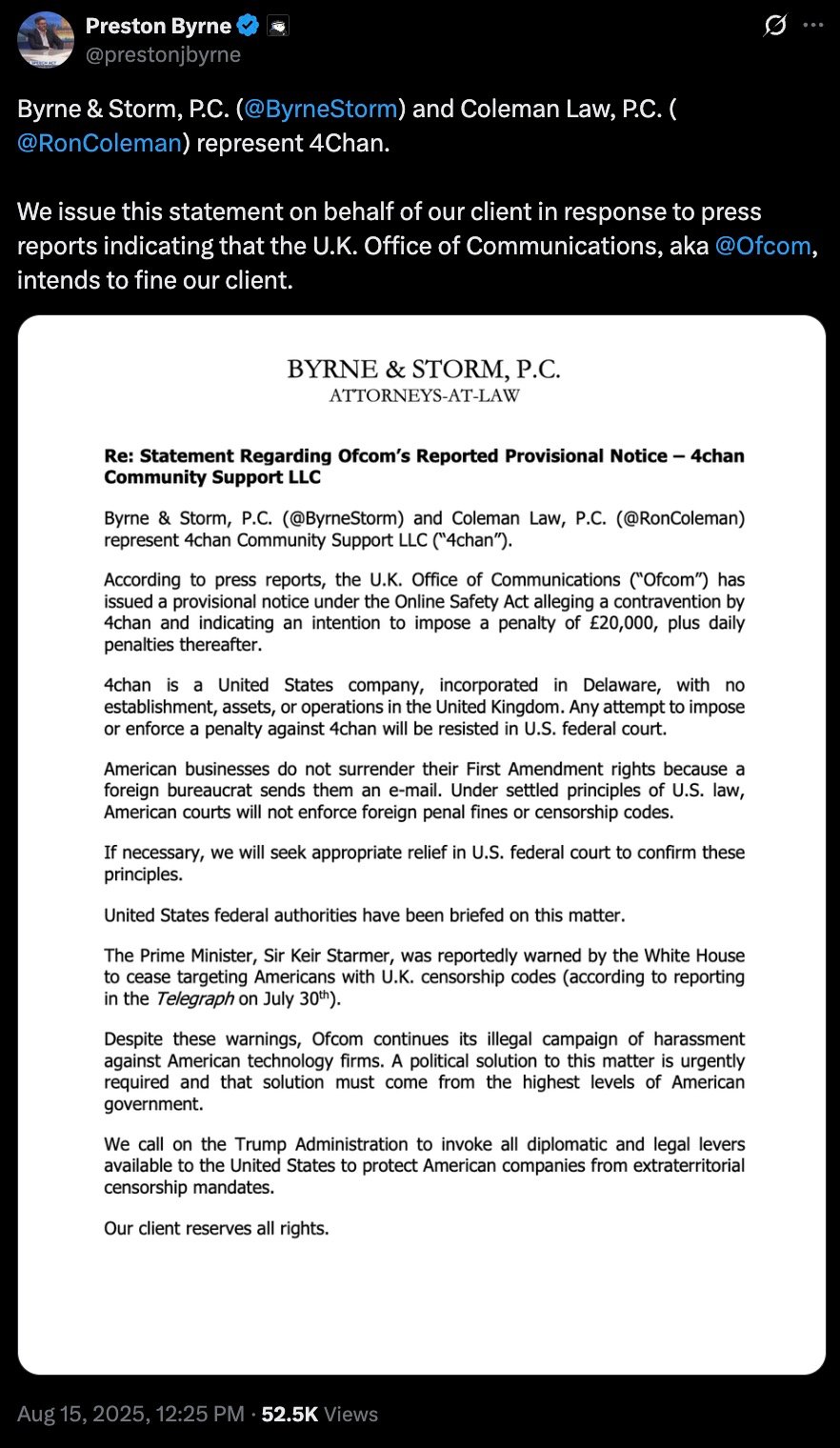

The restrictions have also placed further strain on the UK’s “special” relationship with the US, which is determined to protect the financial interests of its largest companies, while opening up a Pandora’s Box of legal complications.

Even the BBC has reported that platforms are escalating their censorship of content as a result of the OSA, particularly on sensitive issues such as Israel’s genocide in Gaza and the war in Ukraine.

NEW: The BBC is now reporting that information about the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, UK rape gangs, and more is being censored online due to the government’s new Online “Safety” Act.

WELL DONE LADS 🫠 pic.twitter.com/DnSyAxd1wx

— Silkie Carlo (@silkiecarlo) August 1, 2025

Newsweek has described the Online Safety Act “as a masterclass in unintended consequences and symbolic rulemaking”:

When U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer recently told President Donald Trump, “We’ve had free speech for a long time, so, er, we are very proud of that,” one had to wonder—what exactly is he proud of?

Is he referring to the 30 people a day his government arrests for posting “offensive” things online? Or perhaps he is proud of the fact that his government was threatening Americans with criminal charges for not complying with his government’s Online Safety Act?

And while the OSA was done under the guise of protecting kids online, the government is also inexplicably engaged in a Streisand effect moment, with its agency announcing it was investigating four companies operating 34 pornographic websites. Essentially, by calling it out, the regulator told minors where they can go to access pornographic content without the need to utilize age verification…

Britons are pushing back with a petition to repeal the law, which has already gathered over 450,000 signatures (NC: it now has over 500,000). American lawmakers would be wise to pay attention and avoid making the same mistakes in Congress. We can protect children without sacrificing the foundational principles of a free and open internet.

Trojan Horse

Since the implementation of the OSA’s age verification rules roughly a month ago, “all UK internet users only have access to a childproofed version of the web unless we’re willing to undergo intrusive age verification processes,” says Rebecca Vincent of the digital rights group Big Brother Watch. Or, of course, use work arounds.

This is a key point: as we’ve been warning since November last year, online age verification is the Trojan Horse for the mass adoption of digital identity systems, which very quietly became a legal reality in March, 2024.

With the enactment of the OSA, everyone must submit to an online passport check in order to access social media and other large user-to-user services, which the bill refers to as Category 1 services. Facial recognition technologies are also being used despite their myriad flaws. Once we sign up for these verification processes our access to content will be increasingly controlled, warns the tech writer Tim Hinchliffe, citing the UK government’s own explainer of the OSA:

“Adult users of such [Category 1] services will be able to verify their identity and access tools which enable them to reduce the likelihood that they see content from non-verified users and prevent non-verified users from interacting with their content. This will help stop anonymous trolls from contacting them.”

The EU’s Chat Control Legislation poses similar dangers. The Fight Chat Control website highlights six potential risks, intended or otherwise:

- Mass Surveillance. “Every private message, photo, and file scanned automatically: no suspicion required, no exceptions (apart from for EU politicians, who demand privacy for themselves), even encrypted communications.”

- Breaking Encryption. “Weakening or breaking end-to-end encryption exposes everyone’s communications—including sensitive financial, medical, and private data—to hackers, criminals, and hostile actors.”

- Fundamental Rights. “Undermines your fundamental rights to privacy and data protection, as guaranteed by Articles 7 and 8 of the EU Charter—rights considered core to European democratic values.”

- False Positives. “Automated scanners routinely misidentify innocent content, such as vacation photos or private jokes, as illegal, putting ordinary people at risk of false accusations and damaging investigations.”

- Ineffective Child Protection. “Child protection experts and organisations, including the UN, warn that mass surveillance fails to prevent abuse and actually makes children less safe—by weakening security for everyone and diverting resources from proven protective measures.”

- Global Precedent. “Creates a dangerous global precedent enabling authoritarian governments, citing EU policy, to roll out intrusive surveillance at home, undermining privacy and free expression worldwide.”

This is another key point — and it is one that was raised by Meredith Whitaker, the CEO of the Signal encrypted messaging app, in discussions regarding the UK’s Online Safety Act a couple of years ago. Whitaker warned that the UK’s implementation of the OSA would be seen as a precedent by more repressive regimes to double down on their own Internet surveillance and censorship activities. In the words of the UN Human Rights Commissioner, the trend is “unprecedented” and “paradigm shifting”:

The Online Safety Act’s age verification rules are just the tip of the iceberg. Far more alarming is clause 111, which mandates that platforms implement backdoors and spyware upon request, gutting end-to-end encryption and eviscerating privacy.@mer__edith, CEO at Signal,… https://t.co/SSY3vHsyPm pic.twitter.com/DNTx9Fd19d

— Henry Palmer (@HenryJPalmer) July 27, 2025

This also explains why the current direction of travel is so dangerous: it is occurring at a global level.

The online safety act didn’t happen in the UK in isolation. Remember it’s not a coincidence.

The head of Ofcom, Melanie Dawes, is a key member of WEF’s Global Coalition for Digital Safety, also pushing governments to censor anything labelled “misinformation” or “harm.”

The UK,… pic.twitter.com/IM9GE2U1pa

— Bernie (@Artemisfornow) July 30, 2025

While protecting the children serves as a handy pretext for remodelling the Internet, the real driving motivation for regulations like the OSA and the EU’s Chat Control is, well, control — not just for children but for everyone. As Juliet Samuel reports in the Times of London, UK officials even admitted in a recent high court case “that [the OSA] is ‘not primarily aimed at … the protection of children’, but is about regulating ‘services that have a significant influence over public discourse’, a phrase that rather gives away the political thinking behind the act.”