At PING, testing isn’t what happens after design. Testing is design.

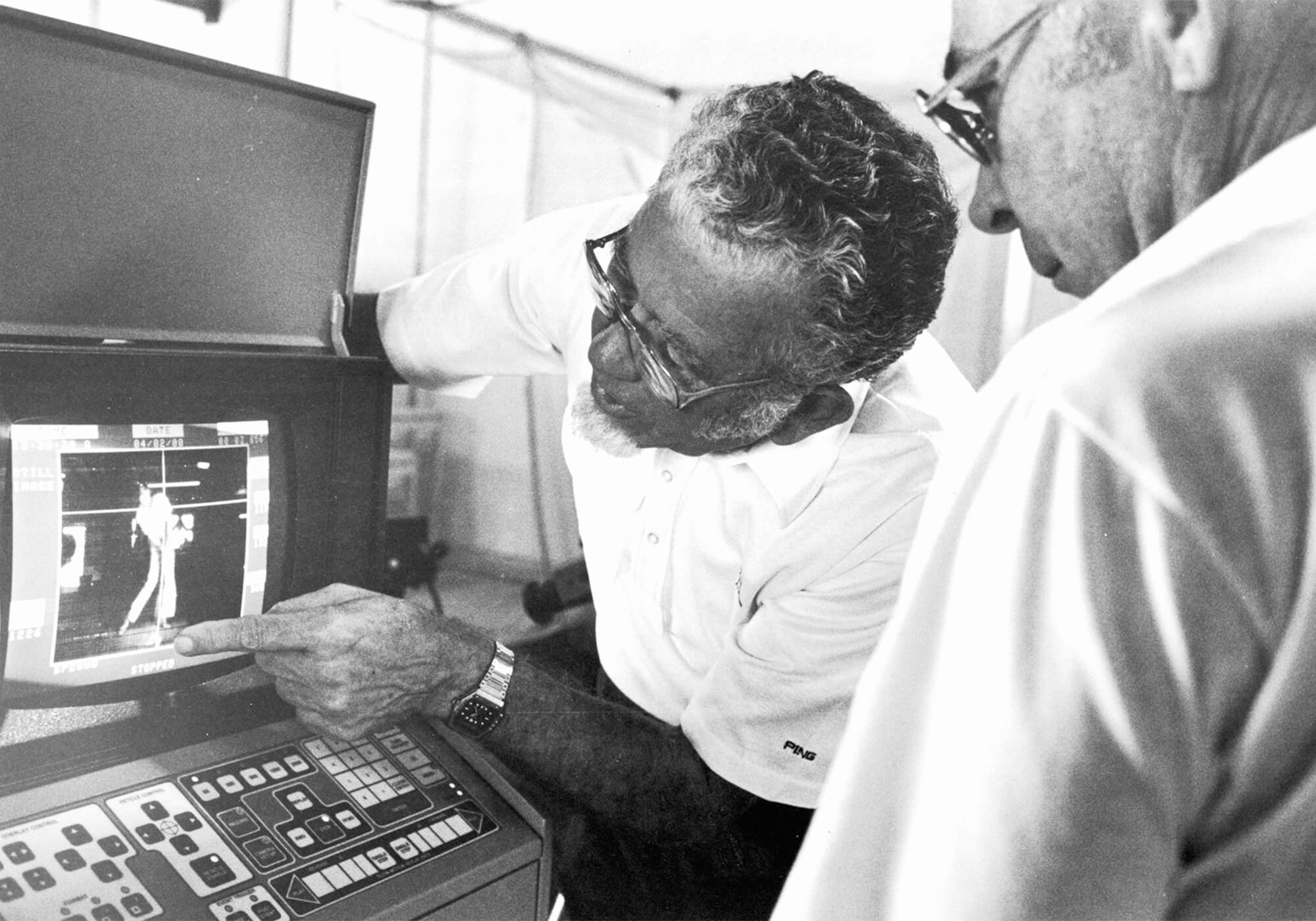

Long before motion-capture rigs, ENZO, FOCAL, or even a robot named PING Man (fun fact: the robot is PING Man, the golfer in some versions of the PING logo is Mr. PING), Karsten Solheim had a car, a desolate strip of road in an undisclosed location in the Arizona desert, and a question.

The story goes like this: PING founder Karsten Solheim and his son Allan are driving through the desert at 100 mph. Karsten hangs out the passenger window holding a persimmon driver attached to a spring gauge to measure aerodynamic drag. No complex computer simulations. No wind tunnel. Just relentless curiosity, an idea, and just the right amount of recklessness.

That image of Karsten in the desert is still intertwined in the company’s DNA. If it can be tested, PING probably has. If the result doesn’t make sense, they’ll test again. And if the results still don’t make sense, they’ll work to figure out why and then test some more.

Tech that lasts

That dedication to testing is no small part of the reason why PING’s most important innovations aren’t trends; they’re fixtures. The Anser putter, Eye2 irons and G-series drivers were engineered not for launch-day headlines but for staying power. Erik Henrikson, PING’s Director of Golf Science, says that’s by design: performance is something you build on, not something you chase.

“Our key currency is knowledge,” he says. “And to gain knowledge, you have to experiment, run tests and understand what happens.”

That mindset produces what Henrikson calls sustainable performance—technology that lasts because it’s grounded in repeatable truth. Once PING finds a quantifiable advantage, it doesn’t abruptly move on to the next big idea; it continues to improve the one it has.

The PING way is perhaps not as sexy as annual barrage of “game-changing innovations” frequently promised by a good bit of the industry but it helps explain why innovations like turbulators, perimeter weighting and PING’s color-coded fitting system still matter decades after their debut in some cases.

Each generation of PING product refines, not resets, the established foundation.

One thing at a time

Arguably, those foundations are rooted in single-variable testing.

Tom Trueblood, Senior Test Engineer at PING, explains that every project starts with a question, not a prototype. “You don’t start with a club and hope to learn something. You start with a question and build a test around it. We’re hyper-focused on single-variable testing. We want to know what one thing does before we ever talk about the system.”

That “one thing” could be something apparent to the golfer: turbulators, a new weighting structure or an updated hosel adapter. Often, it’s things that are all but invisible to the golfer: a paint formula, bonding agents or new groove geometry. The company runs roughly 1,400 tests a year, of which about 15 percent involve players. The rest are built around what may sounds like minutia to the rest of us—plating durability, bend life, even how new adhesives respond to Arizona’s summer heat.

It’s tedious work and a good bit of it doesn’t sound particularly glamorous but it’s how PING turns curiosity into certainty (or near-certainty, anyway). Every measurable property is isolated, quantified and logged so the next guy doesn’t have to guess.

When the pieces come together

Golf clubs don’t exist in isolation. A new epoxy, for example, is only one small piece of a larger puzzle. At some point, somebody has to swing the club. So, once the single-variable work is done, the team turns to system-level experiments—how the sum total of those single variables behaves when a human enters the chat.

“Player testing is the most visible,” Trueblood says. “It’s where everything comes together, the whole system. But it’s also where it’s hardest to separate cause and effect.”

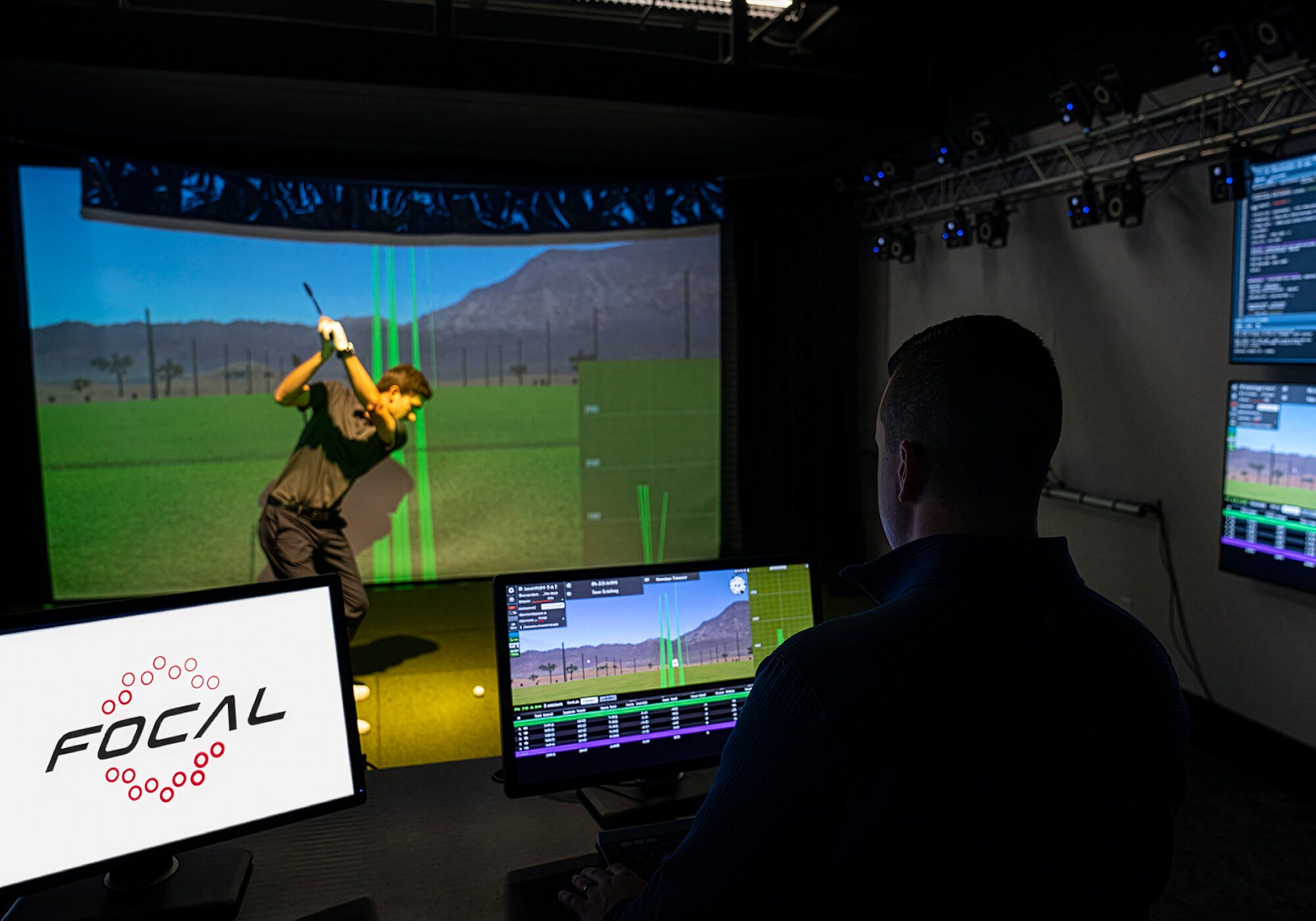

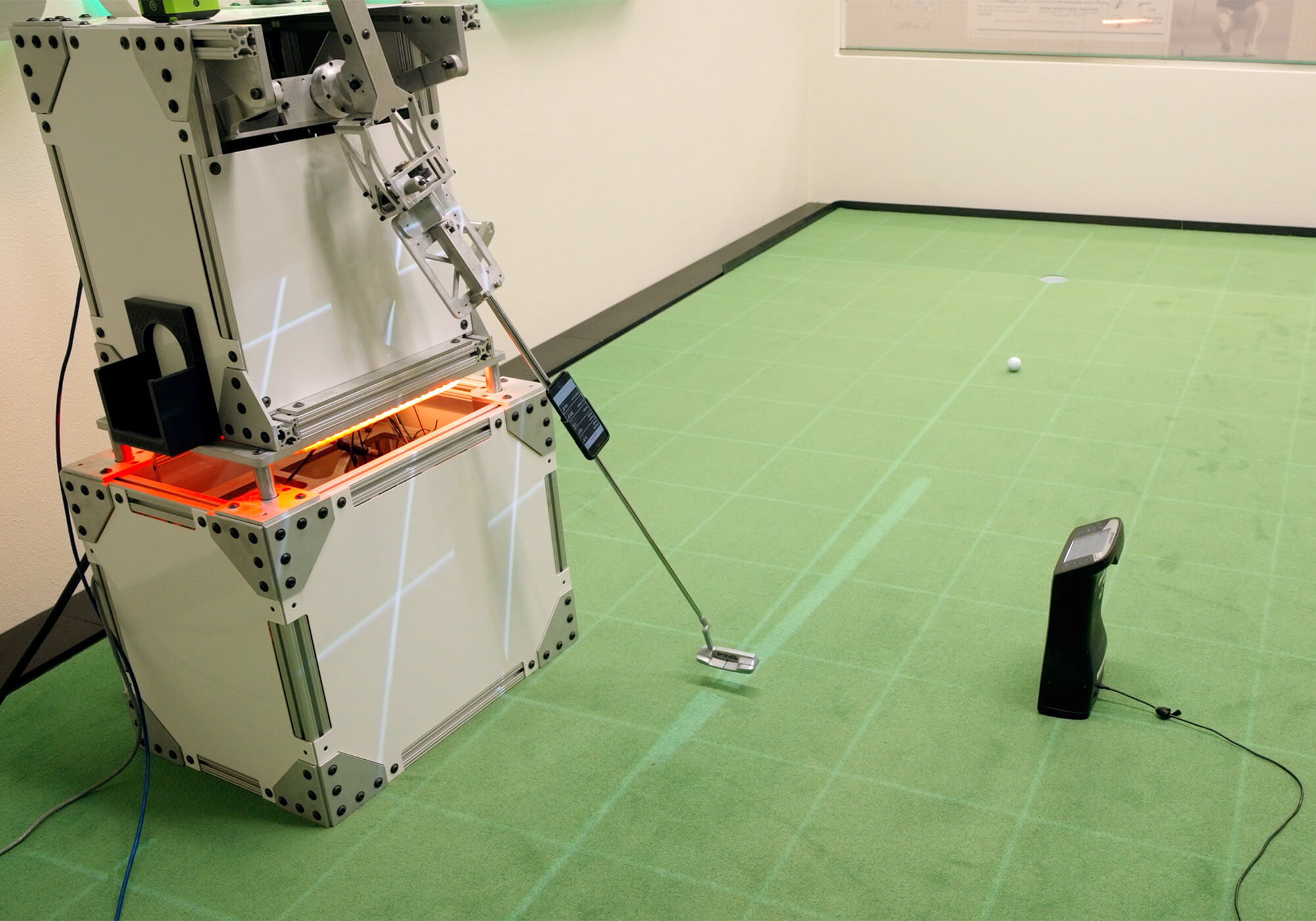

That’s where PING’s layered testing model shines. Player testing tells engineers what happened. PING’s proprietary FOCAL motion-capture shows what the player did. PING Man can help isolate the performance of the club. By overlaying those data streams, they can see exactly how human adaptation interacts with immutable physical design.

Henrikson points to one example. “When you move the CG back on a driver, you get more lead. But players tend to take that lead off—they de-loft the head more at impact. The robot shows one thing, the player shows another. You need both to understand the full picture.”

Defining “better”

For PING, a product doesn’t come to market unless it’s better and the definition of “better” is brutally simple: the new model must outperform the last.

“For most products, the first benchmark is the previous generation,” Henrikson says. “We’ve delayed launches. We’ve canceled products because we could not beat the previous generation.”

One example from recent memory is when PING pushed the launch of the G410 LST driver. At the time, some PING competitors thought the delay was a stunt that would allow the company to juice the market mid-season. However, the truth was that its predecessor, the G400 LST, performed so well that initial prototypes for new model couldn’t best the original.

“Everybody’s sitting around going, ‘Did we create a unicorn?’” Henrikson recalls. “The 400 LST just did something we didn’t fully understand until the 430.”

PING could’ve shipped the G410 anyway. They wouldn’t have been the first golf company to roll with what they had. Instead, they kept working.

The decision probably cost a few million in short-term sales but inside PING’s company walls, better has to mean something. If nothing else, the story serves as a reminder that at PING, innovation drives the calendar, not the other way around.

And when it still isn’t better …

As in the case of the G410 LS, sometimes testing doesn’t produce the decisive win that computer simulations suggest it should. When that happens, PING digs deeper.

Everything has to be checked. Heat treatments may not have been fully cooked, wall thicknesses (in a driver head there can be more than 200 specific dimensions) can drift—there is no shortage of possible suspects.

Were the inputs correct? Did the robot deliver the club as intended? Was there something else in the test environment? Ultimately, is the setback a result of the design or the execution?

Henrikson says finding those answers can be a “CSI Project”—a forensic loop of simulation, prototype and validation where no assumption goes unchallenged. Tracking down the source of small mistakes early in the design process is how PING avoids making bigger ones on retail shelves. It’s a slow process, sometimes, but it’s also why PING rarely releases duds.

Built to last

One of the few assumptions PING makes is that golfers keep their clubs longer than the market wants them to. So durability and longevity are always part of the equation.

“We know a lot of players are four- to six-year drivers,” Trueblood says. “So we think in those terms. Longevity isn’t just durability. It’s performance that stays relevant.”

That’s a succinct way of saying PING doesn’t just build clubs to last physically, it builds them with performance that stays relevant. Sure, the structures have to survive heat, cold, travel, and thousands of swings (not all of them good), but the results have to hold up, too.

While the company is always chasing better, it isn’t interested in making your last purchase obsolete. A PING club is built to perform for years, not just until the next release cycle. That’s the difference between durability and sustainable performance.

The trade-off: Quality versus performance

In testing and design, performance and quality are sometimes opposing forces. Thinner faces can mean faster ball speeds but they also increase the risk of cracks. A new finish might be more aesthetically pleasing but chips under stress. Even the best-performing material can become problematic if it’s too hard to bend or too inconsistent to bond.

“Quality isn’t something you bolt on at the end,” Trueblood says. “It’s a competing constraint you solve for at every step.”

At PING, progress isn’t measured by how far they can push a CAD model. It’s measured by how reliably the final product performs in testing and in production. Sometimes the better design isn’t the one that wins on a launch monitor, it’s the one that performs the same way every time, for years.

That balance extends beyond the player. PING’s engineers know that a design that’s perfect on paper but impossible to build isn’t a success, it’s a bottleneck. Some alloys can push performance but make the bending process physically harder on the build team, adding real fatigue over time. A club has to be faster and stronger but also buildable. The people on the shop floor are part of the feedback loop. If a process adds unnecessary strain or inconsistency, it gets redesigned.

PING’s physics-assisted AI

In an industry where AI is an increasingly popular, although still somewhat nebulously applied, buzzword, PING prefers to promote its HI (Human Intelligence).

That’s not to say it doesn’t have plenty of computing horsepower but PING’s approach to artificial intelligence starts with established physics and its decades of accrued knowledge. Henrikson explains that their models use real swings from real players as inputs. Each swing’s delivery data feeds into physics-based simulations that can run thousands of virtual tests before the first prototype is created.

“We can feed real swings into our models and run thousands of virtual tests,” he says. “We can vary CG, MOI, bulge and roll, COR—optimize for 30 real swings—and see what happens before we ever cut metal.”

Rather than letting algorithms invent golf clubs, PING’s process uses decades of measured data to guide what those algorithms can do. The math serves the physics, not the other way around. The goal, as Henrikson puts it, is to understand, not to outsource curiosity.

The testing pool

PING’s testing pool is largely homegrown: about 150 to 200 employees, from scratch golfers to 20-handicaps. The group is segmented by playing ability and product category. For better-player products like Blueprint, the test pool skews heavily towards elite players, but across most categories, high-handicap golfers feature inside PING’s test pools.

Because every tester’s motion is captured with PING’s FOCAL motion capture system, engineers can select participants by delivery profile rather than just handicap. That same data also powers PING’s simulation models, creating a rare feedback loop between human testing and virtual prediction.

It’s the best of both worlds: engineers can validate simulations against real swings and then use those findings to refine both the club and the model. Henrikson calls it “closing the loop between curiosity and confirmation.”

Unconventional tests

PING’s testing culture isn’t limited to spreadsheets and robots. Some of its most interesting methods border on absurd, even if they serve a purpose.

Henrikson recalls one of the more infamous stories involving John A. Solheim. Early in a putter project, PING needed to check the bond strength of a new insert. Rather than defer to a lab test, he asked an engineer to take it outside and hit it against a concrete curb until it broke. It didn’t. The design passed.

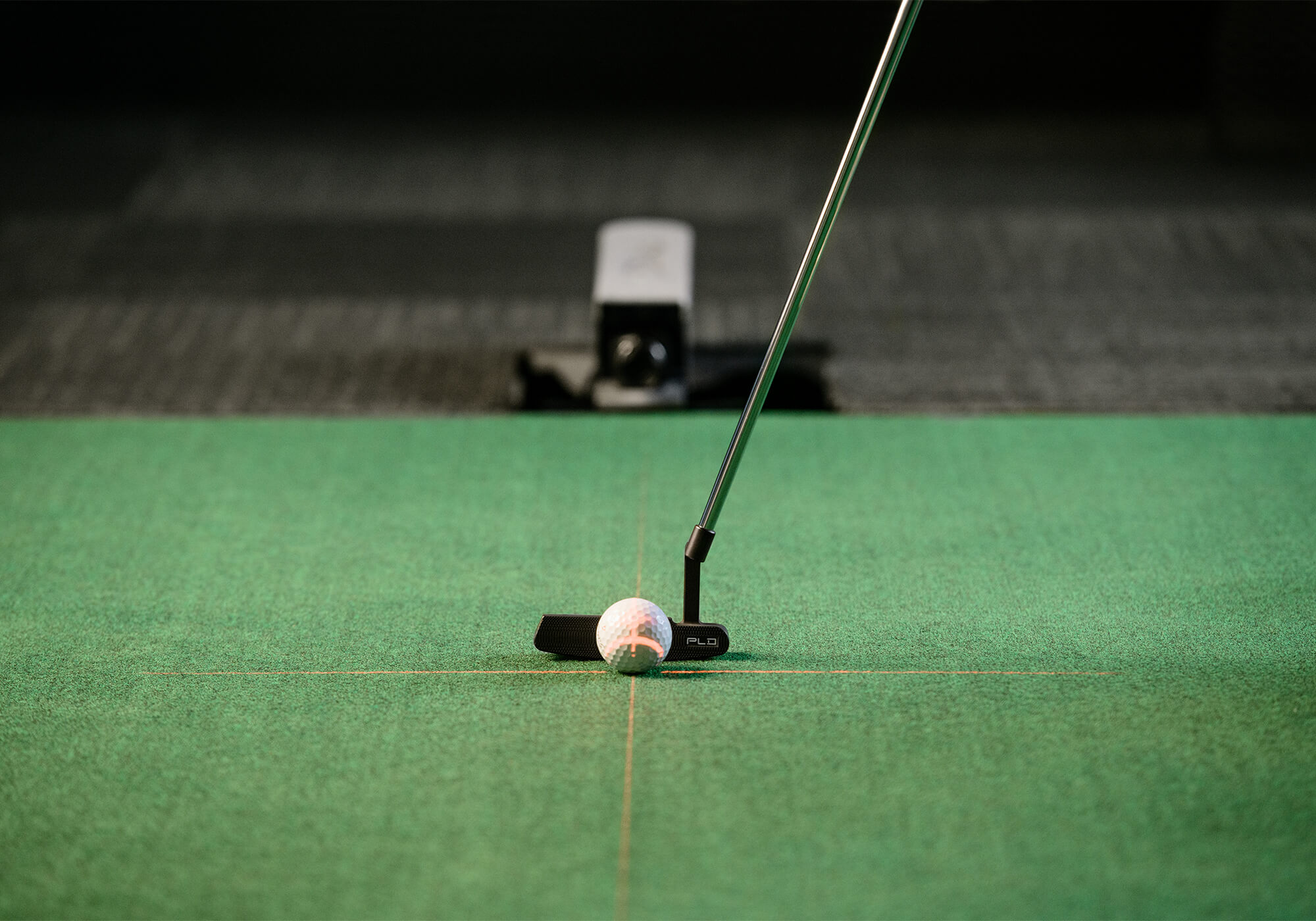

PING has used PING Man to tee off with a putter just to confirm epoxy integrity. Every new model still has to survive a 50-mph putter swing in the robot lab.

There’s also the waterproof-bag test. Instead of relying on lab data, engineers zip the pockets and put the bag under a shower. If it leaks, it fails. It’s a reminder that tests don’t always have to be complex to be effective.

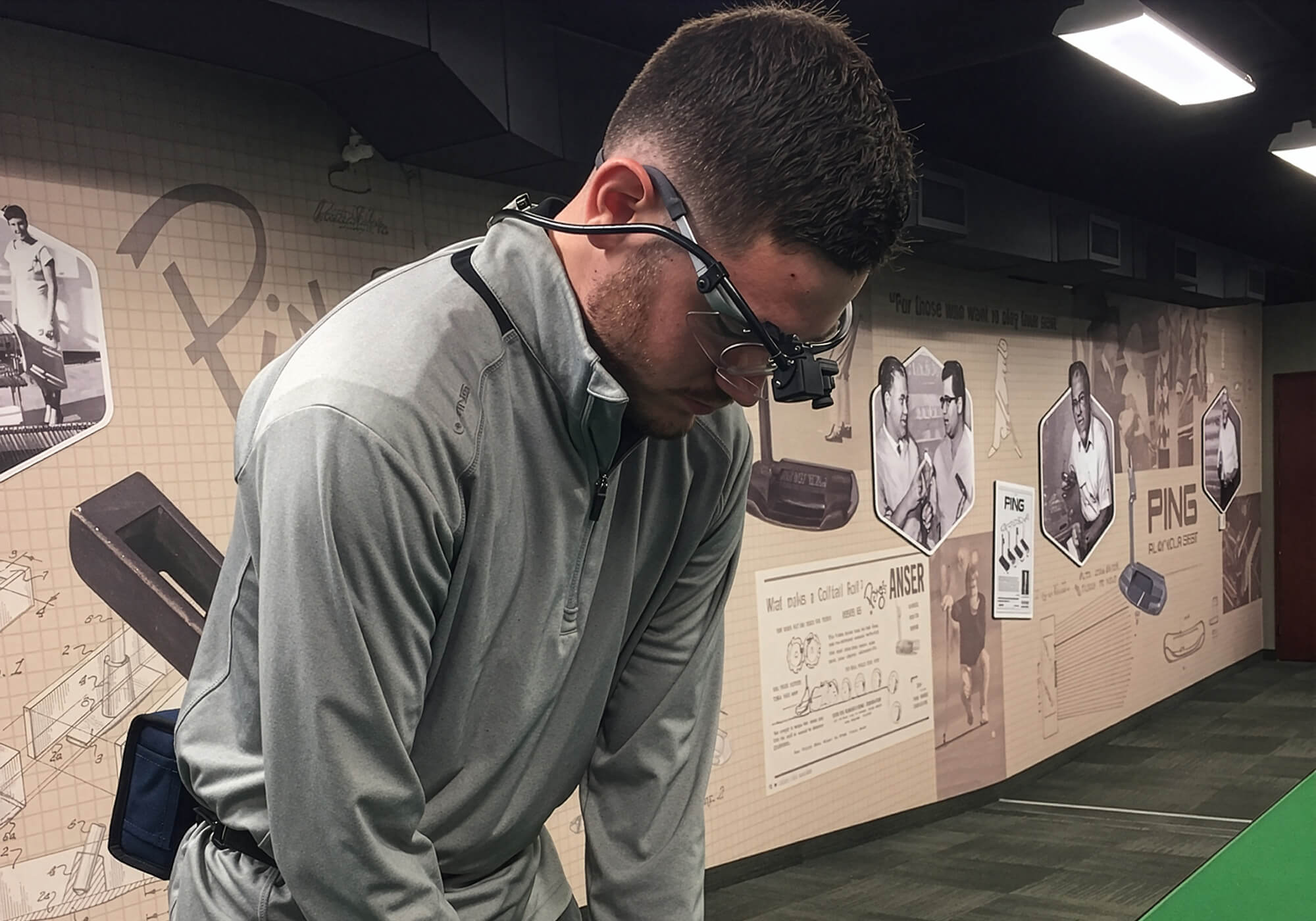

And then there are the creative one-offs—eye-tracking studies to measure how golfers visually process alignment lines. That same test also led to PING changing the placement of the shaft labels on its putters. A leaf-blower experiment was used to make sure headcovers won’t blow away in the wind, and nothing beats an Arizona trunk-bake cycles to simulate heat exposure.

Each one is simple, practical, and born from the same philosophy: don’t assume, test.

The role of the golf ball

The golf ball isn’t an accessory at PING; it’s part of the system.

Trueblood says ball selection shapes every level of testing, from drivers to putters. “Different balls make different sounds and clicks. Whether it’s a groove, an insert or a flat face, it all plays into it.”

That understanding runs deep. PING’s engineers account for how the compression difference between a Supersoft or a Pro V1 changes impact acoustics and feel for different swing speeds. Those variations help define which sound profiles appeal to a given player type.

And while PING doesn’t currently make golf balls, it studies them relentlessly. The company’s Ballnamic project grew out of this same testing mindset: you can’t separate club performance from ball behavior. Change the ball and you change the club.

Hold your conclusions in an open hand

Henrikson laughs when he remembers how often the data humbles them. “Those experiences help you realize how important it is to hold all your conclusions with an open hand. We have better measurement technology now, better tools, and there’s always something you didn’t consider.”

He cites statistician George Box’s famous quote: all models are wrong; some are useful. The trick, he says, is to make them less wrong every year. That’s why PING habitually revisits its history. It’s not afraid to reexamine things like how loft changes affect spin and launch on hybrids. PING’s first hybrid models date back to 2008; updated versions followed in 2015 and 2020. Each iteration makes the predictions more accurate but few things are ever considered entirely settled.

Sometimes things change. Sometimes they don’t, but you don’t know which are which unless you continuously test.

Trueblood says that attitude goes all the way back to John A. “Every so often, someone comes in with a new idea and John says, ‘Yeah, we did that 25 years ago.’ And he’s not dismissing you. It means the science still works.”

The process never ends

For PING, testing isn’t the end of the process; it’s the feedback loop that keeps everything honest. Every delay, every wrong turn, every “why didn’t that work?” moment helps makes the next answer better, even if it’s seldom 100 percent definitive.

The tools have changed but the intent hasn’t. Karsten’s wind tunnel on wheels has become robots, motion capture and simulations, but the reason remains the same: find out what’s real and do it again tomorrow.

At PING, curiosity isn’t what happens between projects. It’s the reason there’s always a next one.

The post The Science Of Curiosity: Inside PING’s Relentless Testing Culture appeared first on MyGolfSpy.