UC System-Wide Academic Congress on the Labor Market Destinations of Recent College Graduates: The UC Systemwide Academic Congress is Oct. 28–29, 2025, focused on recent grads’ labor outcomes, with panels on national and California trends, AI’s impact on entry-level work, employer insights, and UC alumni pathways. It’s open to UC staff and faculty and held virtually on Tuesday, Oct. 28 (12–4:30 p.m. PT) and Wednesday, Oct. 29 (8:30–11:45 a.m. PT). UC’s new Lightcast-powered dashboard mapping alumni employment and skills, showing top destinations like Google, Amazon, Kaiser, and UC itself, and highlighting employer demand for communication, research, writing, and leadership…

<https://www.ucop.edu/systemwide-academic-congress/agenda/index.html>

What I said: At the moment, the unemployment rate in the United States, the all-worker average is 4%: for every 24 people who say “yes, I have a job”, there is one who says “I have not a job even though I have been recently looking for work”. For recent college graduates, however, right now the unemployment rate is 4.8%. Given a 4.0 percent all-worker average, we would have expected the recent college graduate unemployment rate to be something like 3.3% or so.

Note: This is jobs rather than wages. Age and experience adjusted, wages remain much higher for college-educated workers than for non-college-educated workers.

One way to think about it is this:

-

The average unemployment rate for all college graduates currently is 2.7%, two-thirds of the all-worker average.

-

The average young-worker unemployment rate is currently 7.4%, almost twice the all-worker average.

-

Typically, recent college graduates, those age 22 to 27, have an unemployment rate about 1/4 of the way from the college-graduate to the young-worker average.

-

In terms of finding and keeping jobs, young college graduates benefit from the college-worker advantage, but suffer from the young-worker cost. However, the college-worker benefit tends to rule.

-

But right now it isn’t ruling. For the first time ever, the young graduate unemployment rate is halfway between the college-worker and the young-worker rates, and higher than the national average unemployment rate.

As Paul Krugman wrote last week:

Paul Krugman: Bad Times for College Graduates <https://paulkrugman.substack.com/p/bad-times-for-college-graduates/>: ‘[Now] is not the worst job market college graduates have ever seen. It is, however, the worst such market compared with workers in general that we’ve ever seen, by a large margin. [But] nobody knows for sure why this is happening…

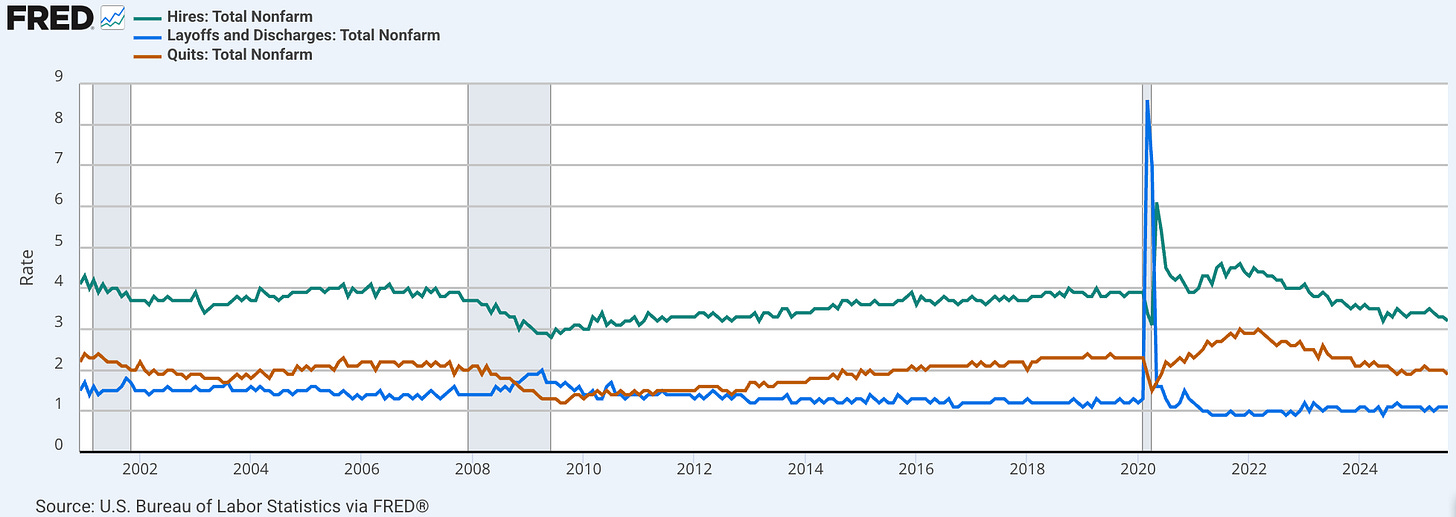

In addition, the labor market level of hiring right now is perhaps depressed by a quarter below what we would expect for a balanced economy at the current unemployment rate of 4%. While unemployment is by no means high in historical perspective, finding a job is about as hard as it has been in 2012-2013, which were not good years for job seekers. Finding a job right now is almost as bad as in a substantial depression.

We thus have two things going on: We have a sluggish hiring system, for reasons we do not understand. We have the a loss of a piece of young college-graduate privilege in matching jobs to workers, vis-à-vis the national average. Recent college graduates are now no longer like college graduates in general than like young workers in general, as far as finding and keeping jobs is concerned.

We do not have any terribly good nailed-down explanations for why this is so. There are intriguing signs, however, well laid out earlier by David Autor and Erik Brynnjolfson, that it may be because employers are thinking:

-

Radically new technologies for college graduate knowledge work are coming down the pike.

-

Employers do not want to make large investments in hiring new workers and staff until things become clear

-

Especially because they overhired immediately after the plague

Plus: because there is now a huge amount of uncertainty in future economic policy: every day brings a new tweet from the president imposing a sudden new high tariff on some narrow slice of industry or on some particular country—in the most recent case because he got mad at the provincial premier of Ontario.

That’s one piece of what’s going on.

Let me shift gears and step back. If we step back, we see that, at least according to standard measurements, since 1870, we’ve had about 2% per year productivity growth year in America. This, however, has been extremely uneven. Every generation, in about four-fifths of the economy, we have 1% per year productivity growth. Things get better in terms of people are more productive and wages rise. Thus for the bulk of the economy there is incremental and understandable and largely undisruptive growth.

But for about one-fifth of the economy, we get 5% per year productivity growth: a quintupling of productivity over a generation.

And so, for the economy as a whole, productivity growth averages out to 2% per year.

However, over the course of each generation, about one-fifth of the economy is completely and totally transformed in how it works and what people do. It is a shifting but overlapping sector of the economy, this part currently subject to disruptive Schumpeterian creative-destruction. Being caught up in this industrial whirlwind is very good if you can take advantage of the possibilities opened by the rapidly changing technology of the particular economic subsector iin which you are. This is, however, very bad for you if, in your occupation, try to do the same thing in the same way that your parents—or, god forbid, your grandparents did. The value of what you are doing collapses. You still do the same thing in the same way. But because there are other and different ways of doing the thing, the amount of money you can collect collapses.

Right now, for the first time, it looks like, with the advent of Modern Advanced Machine-Learning Model technologies, that college graduates are now in the bullseye. Not only is there something happening to make them lose much of their privilege relative to the rest of the labor market, but we also have very good reason to expect that the jobs of highly educated and well-prepared knowledge workers are going to be transformed substantially over the next generation.

I find myself thinking of a Berkeley student who graduated in 2007, with a political economy degree, someone who I did not think of as a STEM person at all. Graduating in 2007, he faced 2008 and 2009. Miraculously, he kept his job, while a lot of other young hires did not. He kept his job because he had one special qualification: He knew how to make Excel get up and dance. And because he knew how to make Excel get up and dance, he was worth keeping around.

With live in the age of the coming of chatbots and other MAMLM technologies, plus all kinds of other potentially wonderful things. But this raises a question: What are the things that we should be training our students at the University of California to do, so that they can then be the people who know how to make the things their employers want done, using the information systems their employers use, get up and dance?

I have a lot of views on this, but I am out of time.

So let me turn the mic over back first to our host and then to Harry Holzer.

And I also said: If I might jump in with two comments. First, what Eric says [about sharp declines in hiring in the most MAMLM-exposed subsegments of he labor market is definitely true. But at the moment, it’s not the case that AI is making certain people in certain subgroups much more productive, and hence you don’t need as many of them. It is the case that a lot of businesses expect that this will be so over the next three or four years.

Te people I talk to say, “Yes, we’re having a lot of teething pains, but things are definitely going this way, and we need to think when we hiring now of what our labor force ought to look like in three or four years.

Second, if I could pick up on David’s report from the Facebook comment that what they need is not more people who know and are familiar with programming languages particular, but rather with higher level skills. The question for us is: what are the higher level skills they need? I’m reminded of a line that my brother uses. He has had a very successful career on Wall Street. He says that the thing he took in college that was most valuable, in a pre-professional sense, was a nine-person seminar in medieval witchcraft he took from historian Stephen Ozment in his junior year. Each week in that seminar they were confronted with a document about medieval witchcraft. In that document people have written things down that are, from our perspective, total lies. How were they constrained in what they wrote? Why did they feel they have to write these lies? And how do you then try to get through this document to at least guess at what the truth of what was really going on? This was, he says, remarkably good preparation for listening to quarterly earnings calls from throughout his career.

And let me leave that there.

And I also said: I would like to throw half of that question back over the wall back to you sociologists. The obvious thing that you would want to do now, if you think that because of AI you may well want a workforce that’s significantly smaller in five years, that you would fire you experienced engineers and hire a bunch of young people who are teched up in the newest programming languages, have lots of fluid intelligence, and so forth, and who are really, really cheap.

Remember what technological change did to AT&T’s workforce throughout its history. AT&T had 200,000 women in the late 1920s who were plugging cables into switchboards. And now it has zero, with the automatic switches mostly coming in in the 1940s and 1950s. That was one of the few jobs that women were allowed to have back in the 1920s. It was a huge deal that women could no longer get a job at AT&T working as a switchboard operator,

But today’s Silicon Valley firms are not firing. They are, rather, not hiring much. I think the reasons are largely sociological. They are trying to keep their employees imagining that they are in a long-term gift-exchange relationship with a benevolent entity that is a corporation, rather than objects that are of zero concern to their employer.

That is half of it, I think.

As for the other half: I think Harry has very informed views as to the things affecting the labor force and the causes of the current semi-freezing of hiring. I think David is right about monetary policy playing a large role in generating employment weakness. But I am also very much attracted to the uncertainty hypothesis. At the best-paid level of the white -ollar labor force, hiring a worker is a lot more like buying an expensive machine that will last for a long time rather than buying, say, a laptop that will be obsolete in three years. You’re making a 15-year commitment. In times of high uncertainty, the option value of waiting to see what happens until uncertainty is resolved before you make that commitment is very, very high. And so firms are waiting. But uncertainty is not dissipating. Rather, the chaos quotient is growing.

And I also said: I am being a bad panelist. We’re hogging too much of the time here. But yesterday I ran into the former engineering dean here at Berkeley, Shankar Sastry, who said that it was computer science that was being most disrupted from the coming of MAMLMs. Simply put, in their courses, the scores on homeworks are now 20 points higher than they were three years ago, and the scores on exams are all 20 points lower.

I interpret this as the people on the frontline teaching the courses are still focused too much on trying to persuade people to not use AI as they do their problem sets so they actually build the skills. I interpret this as their not being focused enough at the fact that the abstraction layer on which you ought to be teaching computer science is changing, and is changing rapidly. Back in the real old days, computer science courses would start with the quantum-mechanical orbital structure of the phosphorus atom, and what happens to the extra electron when you take a phosphorus atom and shove it into the middle of a silicon crystal. Today, that is almost nowhere in the computer science curriculum, even though it is absolutely fundamental. It is at an abstraction layer at which very few people work: a few wizards at the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation, and a few others.

Thus I think provosts and such need to be looking hard at engineering schools and their computer science departments and asking: what is the right abstraction layer at which to teach to your students? They are not going to be working in the computer industry of five years ago. They are going to be working in the computer industry of 15 years from now. So provosts and such need to hold their engineering deans’ feet to the fire!

And I also said: Just to pick up on a point that David made about Richard Freeman’s The Over-Educated American. Back when i was a freshman, Richard Freeman came to the Ec 10 class and gave his “over-educated American” lecture. He told us that we were there in college to enrich our lives. He told us that if we thought we were in college in order to get a higher-paying job, we should go drop out, take the money that we had invented we were earmarked to pay for college, and invest it in the stock market. He told us that it would be by far a better way to make money than going to college.

That is not true now. If you can get your BA, and if it shows you actually buckled down and learn something in college, he college-high school wage premium is 80% here in America today. If you want a market yelling for something, saying “we don’t have enough of these people” you have one. The market is yelling for more four-year BA graduates.

UCOP: We invite you to attend the UC Systemwide Academic Congress on the Labor Market Destinations of Recent College Graduates, October 28 – 29, 2025 <https://link.ucop.edu/series/uc-systemwide-academic-congress-on-the-labor-market-destinations-of-recent-college-graduates/>. We’re bringing together distinguished economists from across the country, leading researchers within the UC system, influential public figures, and industry experts to discuss emerging national and statewide labor market trends, the impacts of AI on entry-level employment, and how UC data can be used to inform academic planning and support student success. This event is open to all UC staff and faculty members.

12:00 p.m. – 12:10 p.m. Opening Remarks: Katherine Newman, Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, UC Office of the President

12:10 p.m. – 1:30 p.m. Session 1: National Labor Market for Recent College Graduates: David Autor, Erik Brynjolfsson, Bradford DeLong, Harry Holzer, Moderator: Katherine Newman, Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, UC Office of the President

1:45 p.m. – 3:00 p.m. Session 2: California Labor Market for Recent College Graduates: Sarah Bohn, Juan Barrios, Peter McCrory, Jesse Rothstein, Moderator: Su Jin Jez, CEO, California Competes

3:15 p.m. – 4:30 p.m. Session 3: Employer Insights on UC Alumni in the Workforce: Jim Kaplan, Scott McGregor, Ameet Shukla, Ben Thomas, Moderator: Lori Kletzer, Professor of Economics and Former Campus Provost and Executive Vice Chancellor, UC Santa Cruz

8:30 a.m. – 9:00 a.m. Session 4: UC Alumni Pathways and Labor Market Data: Pamela Brown, Chris Furgiuele,

9:00 a.m. – 10:15 a.m. Session 5: Ongoing Labor Market Challenges: Panel of faculty members including computer science, engineering to discuss labor market challenges – such as industry layoffs and impact of AI – and how they are adapting academic planning and programs, courses, and/or certifications: Marios Papaefthymiou, John D. Skrentny, Mary Walshok, Moderator: Richard Arum, P

10:30 a.m. – 11:45 a.m. Session 6: UC Career Centers: Preparing UC Students for a Transforming Workforce: Sean Gil, Andrea Hanson, Carina Salazar, Moderator: Pamela Brown,

11:45 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. Closing Remarks

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…