Yves here. This VoxEU column, originally titled Recent patterns in global risk behaviour in financial markets, seeks to measure a “safe-haven factor” for the dollar and ascertain how it has operated over time and since Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariff shock and his subsequent trade flip-flopping. What this analysis finds is contrary to the impression many get, particularly from geopolitically-minded YouTubers: that the dent to dollar credibility normalized in May and has been pretty stable since then.

I would have been happier if this analysis had gone back to the 1970s, a period of serious and sustained dollar weakness. Then, the Carter Administration even floated a bond issue in Deutsche marks to get a better rate. From the New York Times in 1978:

The United States; borrowed West German marks today for use in currency markets to support the international value of the dollar.

It was the first public borrowing by the United States in a foreign currency, and it took the form of an offering of bonds, denominated in marks, for sale to bankers and other large investors in Germany.

The move is regarded as recognition by Washington that it must assume greater responsibility for. stabilizing the value of the United States currency — which is also the chief world currency, widely used for trade and investment.

Today’s offering of investment securities in marks, equivalent to $1.25 billion to $1.5 billion, signals the beginning of the Treasury’s unprecedented attempt to borrow up to $10 billion in foreign currencies from German, Swiss and Japanese investors. The marks acquired by the Treasury through the sale would be used to buy unwanted dollars when the American currency is being sold heavily in foreign‐exchange markets. Such purchases would tend to bolster the dollar’s value.

In the end, so-called Carter bonds were issued only in Deutsche marks and Swiss francs.

We did point out after the April sell-off in both the dollar and Treasuries that the US was implicitly being assigned a high risk premium by investors. We did not add that we had first come across this idea in the early 1980s. Part one of the anecdote, from a July post:

In the early 1980s, as a wee young thing at McKinsey, I was asked to value a US client’s possible acquisition of a stake in Mexican manufacturer. There was a massive gap between what the buyer and seller thought was a reasonable price.

I went to the Mexico City office to obtain information that would help with a valuation, such as help calibrate the buyer’s assumptions about growth and margins.

Within a couple of days of a week-long visit, I was storming around the office, complaining that there was no data in the entire Mexican economy.

The consultants in the office agreed. One said, “We do a lot based on feelings.”

Part 2 was that your intrepid-then-consultant nevertheless manages to come up with the key variables to put together a proper valuation model, working from the forecasts provided by the seller. It turns out the literally 10x gap between the seller’s ask and the buyer’s bid was entirely logical from each of their vantages. A US owner would have to pay more in labor costs (that’s how the unions rolled) and would face higher taxes than the current Mexican owner.

But far and away the biggest factor was the difference in discount rates each party would use. A US investor would assign a 15% to 20% premium to the Mexican discount rate to factor in the currency and country risk.

Mind you, any foreign investor (save in a very high risk country like, say, the Sudan) would assign a discount rate premium to invest in the dollar as opposed to the home currency even in better times. But the point of the Mexico anecdote is that risk premium has increased thanks to Trump.

Keep in mind also that the volume of foreign exchange transactions due to trade is a very small proportion compared to the amount resulting from investment transactions. Per the BIS, trade is only about 3% of the total.

One reason for the continued outsized role of the dollar may be the depth of hedging instruments in the dollar, particularly for commodities. I was very surprised to learn from John Helmer, in an interview with Dmitry Liscaris, that the famed Russia-Indian oil trade was still taking place in dollar terms. I speculated then that this might not be due just to an odd fracas between Russia and India as to who was responsible for what in setting up their rupee-rouble payment systems but might also have to do with hedging, which can be done in any size only via the dollar. These are some of the key bits from Helmer, which didn’t fully lay out the scope of the impediments. Nevertheless, from his transcribed remarks:

The issue is whether the Indian side and the Russian side can resolve the most serious payment problems that they have encountered which from the Indian side is a failure on the Russian side. Principally central bank governor Nabillina, the central bank of Russia. is extremely sluggish in implementing the bilateral payment schemes between oil priced in an American currency, oil sold for rupees or dollars or rubles and achieve an effective exchange transaction exchange. This first problem and the Indian side sees it as a Russian problem to solve.

And in these new warfare conditions, I’m willing to bet you the Russians will solve it because Governor Nabiolina is an opponent of the current war and cannot continue to block effective Russian waging of resistance the economic war. So I expect the Indian/Russian payment inter payment problem to be solved…

Second, the question of where the discount is paid, how it’s how in particular the UAE, Dubai, Abu Dhabi mediators or middlemen or intermediary systems for managing this discount and affecting the trade will work. Now the Americans understand this very well and they’re escalating. You can read the wire services against the UAE banking system to try to stop Russian Indian intermediation through Dubai.

They’re, the Americans are attempting to crush UAE facilitation as they successfully crushed the Cyprus one some years back. So first there has to be a solution to the rupee-rouble-dollar problem. The Russians have to stop requiring the denomination of oil transactions in in US dollars and find the way. I believe they will find the way.

Another issue is that countries that run dirty currency floats (many!) are likely to be taking steps to keep theirs from rising too much versus the dollar. Tariffs have created an effect similar to an unwanted currency revaluation higher. The last they want is more of the same.

See one case study:

As you can see, the baht got to be very cheap when the Fed increased rates during the Biden inflation. But even with the post-Liberation Day increase, it is not all that high by historical standards (which is what you would expect if were had hit a dollar revulsion scenario). But with the local economy not all that strong and tourism levels flagging, both the press and many privately are arguing that interest rates and as a result, the baht are too high relative to what current conditions warrant. But the officialdom does not want to be seen as depreciating the currency so as to counter the effect of the tariffs. And even though I am not a trader, the currency price action even when big news breaks is so blunted as to suggest that the central bank, at least for now, is intervening to keep it in a trading range.

Mind you, that does not mean that this new standoff of sorts will prove to be stable, particularly with Trump as chaos-generator-in-chief. But it does illustrate that the underlying currency dynamics are so complex that linear assumptions are likely to be inaccurate.

By Magdalena Grothe, Senior Lead Economist European Central Bank, Peter McQuade, Martino Ricci, Senior Economist European Central Bank, and Luca Tondo. Originally published at VoxEU

Following the US tariff announcements in early April, the US dollar strongly depreciated while US Treasury yields rose. This column zooms in on the April episode, analysing the co-movement of asset prices with an estimated market ‘safe-haven factor’. It shows that the co-movement of the US dollar with the ‘safe-haven factor’ changed in April, and that instances of changing co-movement have been at times observed in the past. It further illustrates that available US portfolio investment data for April showed high shifts in demand for US assets, but such shifts were not unprecedented in scale and appear to have normalised since May.

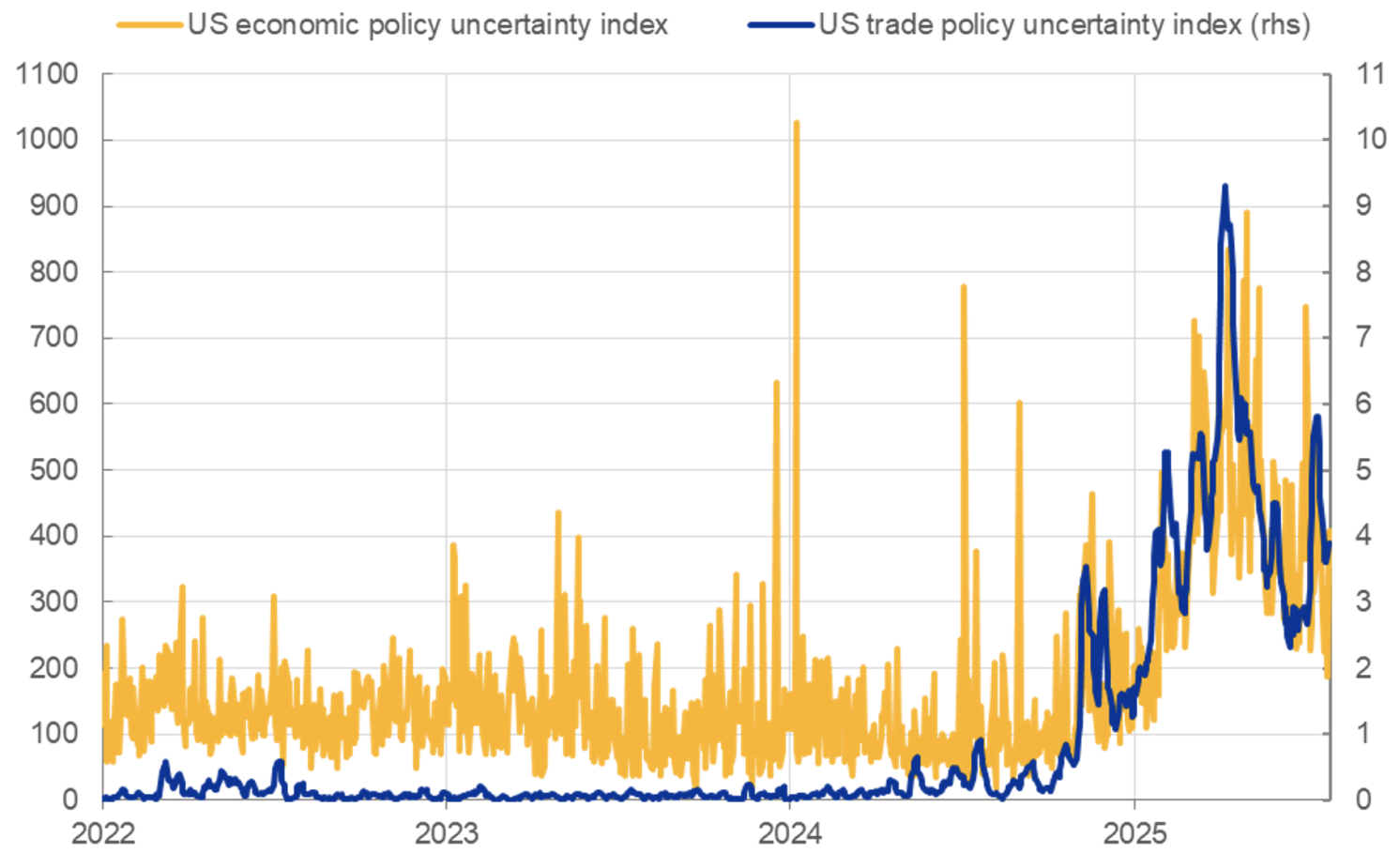

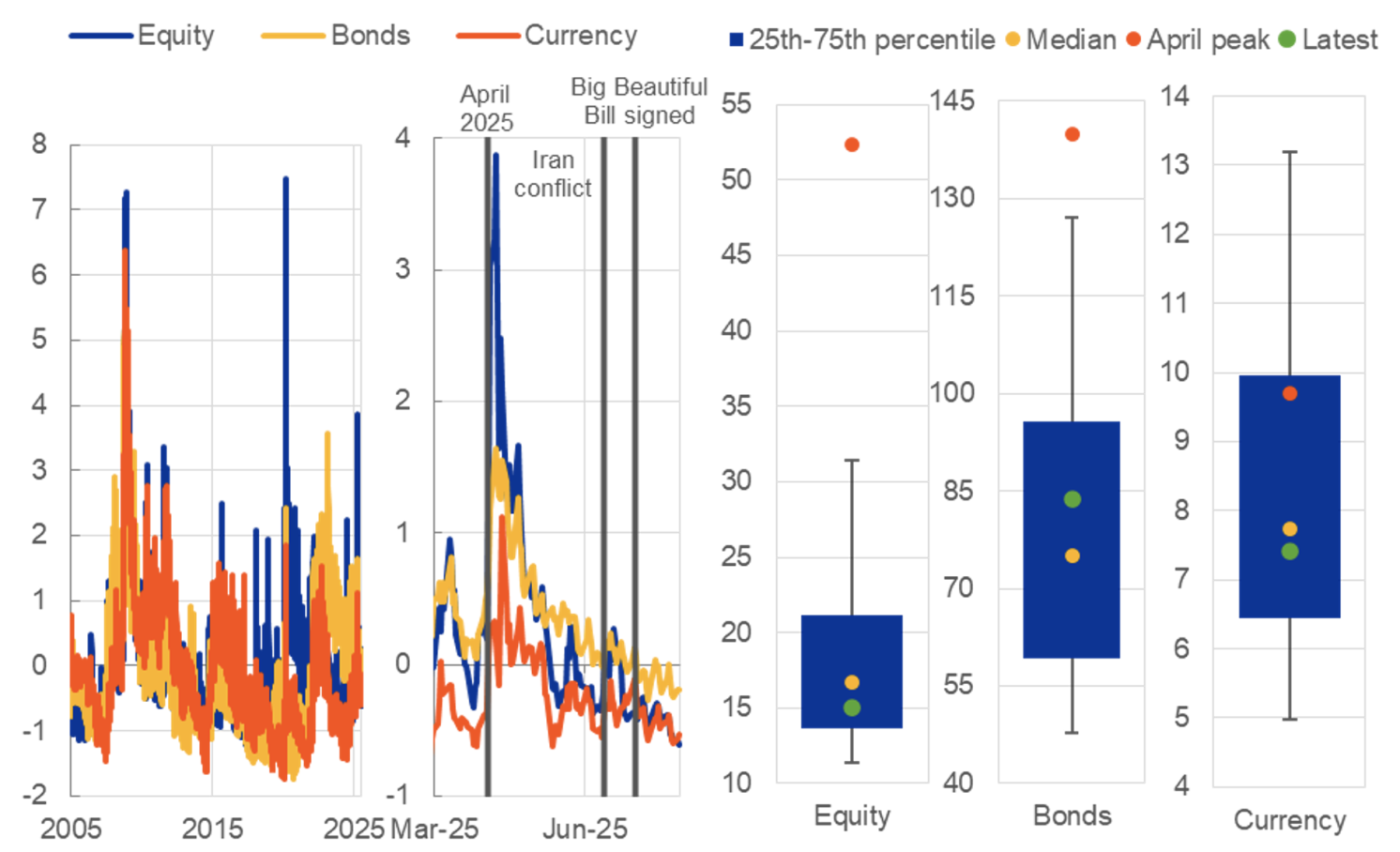

In recent months, global financial markets have witnessed episodes of heightened volatility, with trade tensions being a key source of uncertainty. The first half of 2025 was marked by rising uncertainty, reflecting a combination of factors including rising trade tensions, shifting geopolitical dynamics, and growing concerns about fiscal sustainability in the US (Figure 1). The emphasis on trade policy as a key policy instrument by the current US administration culminated in the announcement of sweeping tariffs on its trading partners on 2 April 2025. This announcement resulted in pronounced bouts of financial market stress in the days that followed. The VIX index – a widely recognised gauge of market volatility – surged beyond 50, reflecting an acute rise in uncertainty and heightened risk aversion among investors (Figure 2). Similarly, option-implied volatility in bond and currency markets spiked, as uncertainty about future interest rate and exchange rate developments mounted, partly linked to worries about the potential implications of the shift in trade policy. The scale of volatility increases in April was substantial from a historical perspective, but in the months that followed, market uncertainty has recovered to relatively average levels, in spite of further geopolitical and economic uncertainties (Figure 2, zoom-in window in the left panel, as well as red and green dots in the right panel).

Figure 1 US economic and trade policy uncertainty indices

<

Sources: Bloomberg, based on Baker et al. (2016) and policyuncertainty.com.

Note: The latest observation is for 28 July 2025.

Figure 2 Option-implied volatility

(left panel: standardised indices, right panel: index)

Sources: Bloomberg and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: ‘Equity’ denotes the VIX index (one-month option-implied volatility of the S&P 500 index), ‘bond’ denotes the MOVE index (one-month option-implied volatility of US Treasury futures for two, five, ten, and 30-year maturity), ‘currency’ denotes the one-month option-implied volatility of the USD/EUR exchange rate. Left panel: Option-implied volatilities are standardised using z-scores. Vertical lines denote the following events: (1) ‘April 2025’ refers to the tariff announcement on 2 April 2025, (2) ‘Iran conflict’ refers to the start of the Iran-Israel conflict on 12 June 2025, (3) ‘Big Beautiful Bill signed’ refers to 1 July 2025. Right panel: Distributions of (not standardised) option-implied volatilities are calculated since 2010, bars denote 25th-75th percentile range, lines denote 5th-95th percentile range. April peak refers to 8 April 2025. The latest observation is 28 July 2025.

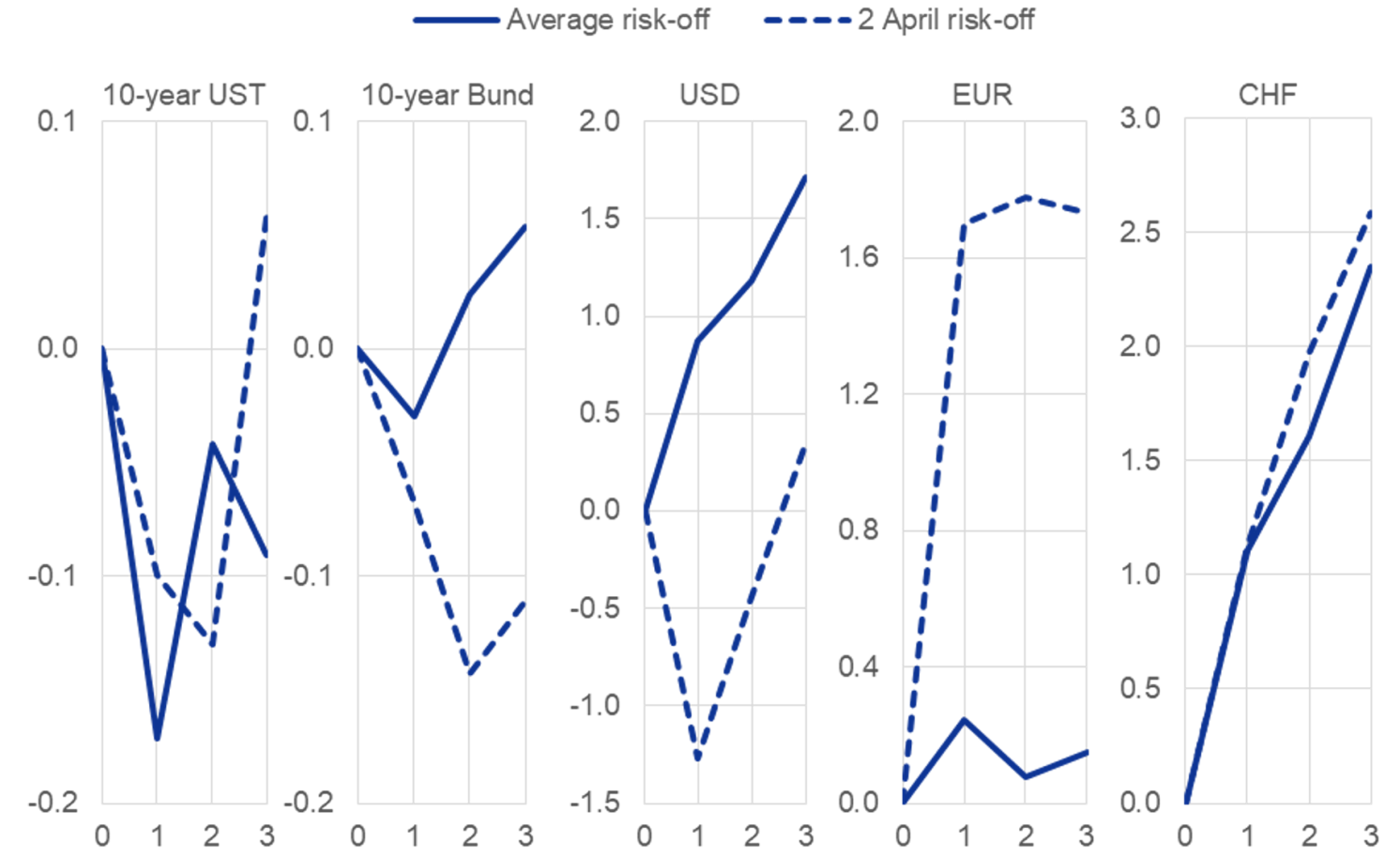

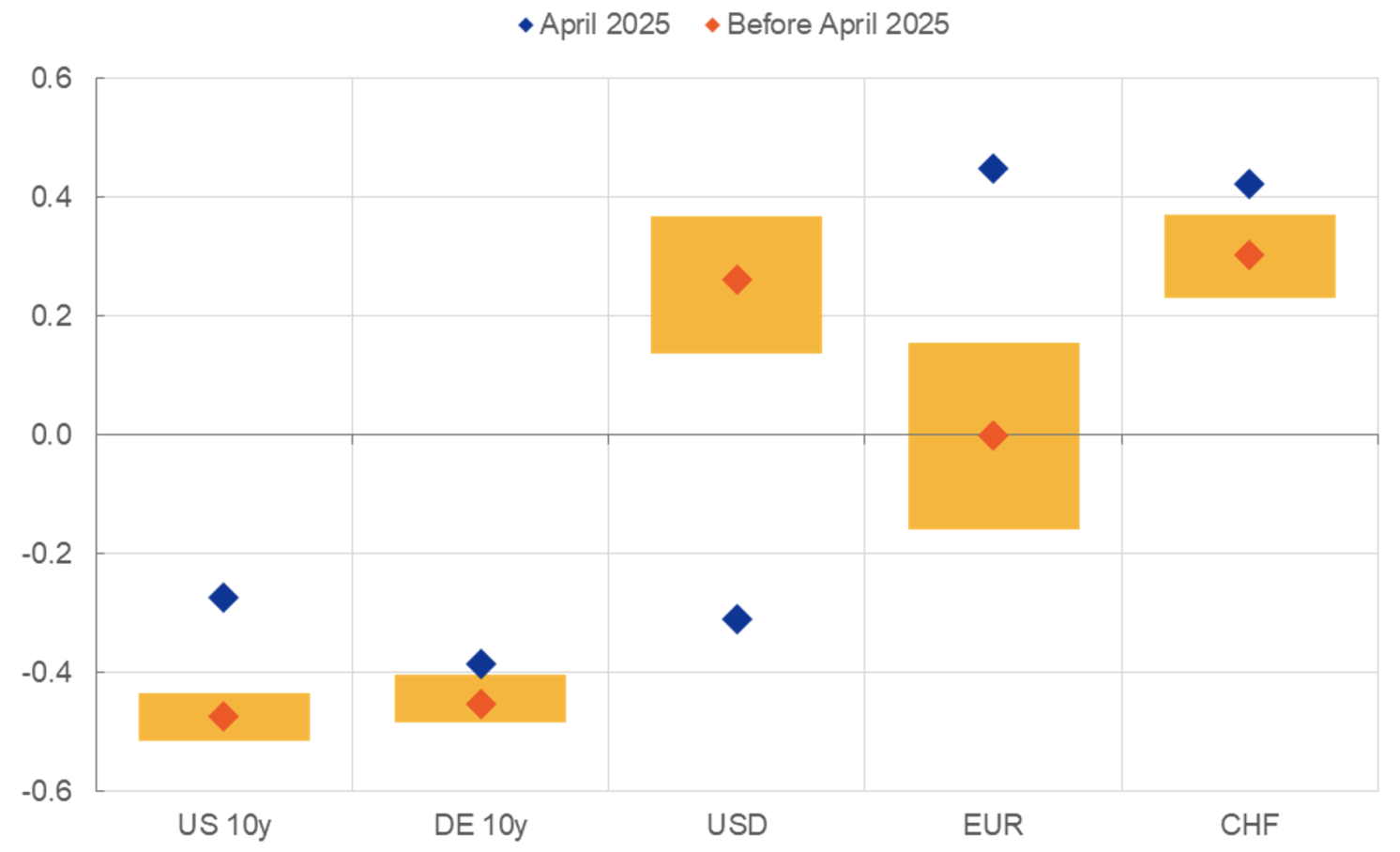

Cross-asset correlations observed after 2 April 2025 were different from those typically observed in risk-off episodes. The April events appear to have increased risk aversion among investors, prompting them to rotate into safe-haven assets. Typically, global risk-off episodes trigger safe-haven flows into safe currencies and bonds. In the past, such flows tended to temporarily lower yields on highly rated sovereign bonds such as US Treasuries and German Bunds, while the US dollar and other safe-haven currencies like the Swiss franc typically appreciated (Figure 3, solid blue lines). In early April, market perceptions of global risk increased, and volatility indices spiked. US yields fell initially, in line with historical patterns, but started to rise sharply after two days (Figure 3, dotted blue lines). Unusually, these developments in the VIX and US yields were accompanied by a depreciation of the US dollar and a strengthening of the euro. 1 In the months that followed, markets experienced another, much smaller and short-lived bout of uncertainty, following the events of mid-June related to the escalation of the conflict in the Middle East. In contrast to the April episode, this adverse geopolitical risk shock saw a slight appreciation of the US dollar.

Figure 3 Response of financial assets to major ‘risk-off events’

(cumulative percentage change)

Sources: Haver Analytics and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: EUR, USD and CHF refer to broad nominal effective exchange rates. Average response is calculated around the five biggest daily VIX-change episodes. ‘2 April risk-off’ shows the response after Trump’s tariff announcement.

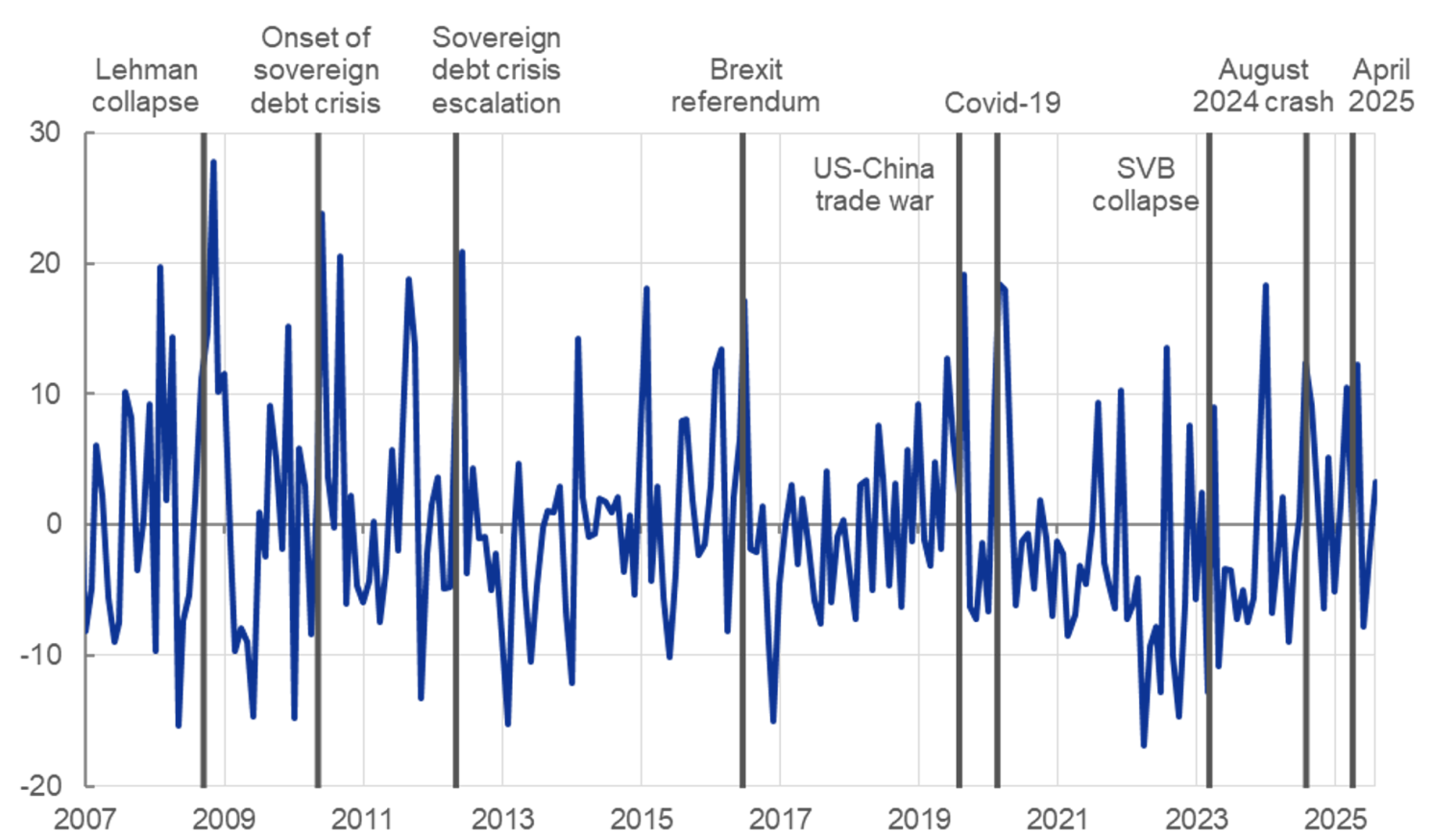

To zoom in on the safe-haven behaviour of investors in April, we estimate a ‘safe-haven factor’. In our analysis, we derive a ‘safe-haven factor’ by modelling the co-movement among the major safe-haven assets, currencies, and key risk indicators. In particular, the ‘safe-haven factor’ is estimated as the first principal component of daily changes in the nominal effective exchange rate of CHF, JPY, USD, EUR, gold price returns, the first difference of ten‑year government yields for the US, Japan, and the euro area, and changes in the VIX index. All returns are standardised using z-scores to account for different variances across the indicators. The US dollar and euro are purged by domestic monetary policy and macro shocks estimated using the model of Brandt et al. (2026). For example, the US dollar return component used for the estimation of the ‘safe-haven factor’ is the residual from the regression of the daily USD net effective exchange rate returns on the US monetary policy and US macro shocks. The euro return component is the residual from the regression of the daily EUR net effective exchange rate returns on the euro area monetary policy and macro shocks. Our approach to use purged USD and EUR net effective exchange rate variables helps us control for major fundamental factors that might be influencing their developments and focus on the residual dynamics of these currencies. In addition, we purge gold price returns from the impact of the USD exchange rate developments by taking the residual from the regression of the gold price returns on the USD net effective exchange rate returns. The ‘safe-haven factor’ resulting from the principal component analysis explains around one third of the variance of its components and indicates the largest increases, among others, in late 2008 during the peak of the Global Crisis, in June 2016 after the Brexit referendum, in early 2020 during the Covid crisis, in August 2024 during a stock market plunge and unwinding of carry trades, as well as in April 2025 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 The ‘safe-haven factor’

(index)

Sources: Haver Analytics and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: The ‘safe-haven factor’ is estimated as the first principal component of daily changes in the net effective exchange rates of CHF, JPY, EUR, and USD (purged by monetary policy and macro shocks estimated using the model of Brandt et al. 2026); gold price returns (purged from the USD); the first difference of ten‑year government yields for the US, Japan, and the euro area; and the VIX. The estimation is daily from 2006 to 2025, the line illustrates cumulated monthly sums of the factor, while vertical lines denote the following events: (1) ‘Lehman collapse’ in September 2008, (2) ‘Onset of sovereign debt crisis’ refers to Greece receiving a bailout package in May 2010, (3) ‘Sovereign debt crisis escalation’ refers to the escalation of the European sovereign debt crisis due to Greek’s political instability in May 2012, (4) ‘Brexit referendum’ in June 2016, (5) ‘US-China trade war’ refers to the reciprocal imposition of tariffs during the first Trump administration, (6) ‘Covid-19’ in February 2020, (7) ‘SVB collapse’ in March 2023, (8) ‘August 2024 crash’ refers to the stock market plunge in August 2024, and (9) ‘April 2025’ refers to the tariff announcement. The latest observation is 28 July 2025.

Model evidence confirms that the co-movement of certain financial market variables with a safe-haven factor was different in April. Our principal component analysis further illustrates the different nature of the April 2025 risk-off episode. Figure 5 shows a typical co-movement of each variable with the ‘safe-haven factor’, estimated over the period from 2006 to March 2025 (red dots), as well as a range of the co-movement, estimated as +/- one standard deviation range of results using a three-year rolling window (yellow ranges). The typical co-movement is compared to the estimates for the period of April-July 2025 (blue dots). Typically, US Treasury yields co-move negatively with the ‘safe-haven factor’ (Figure 5, red dots and yellow ranges). This reflects the fact that US Treasury yields typically decline during periods of global risk aversion as the demand for US Treasuries increases. In the period following 2 April, however, US yields exhibited a less negative co-movement with the ‘safe-haven factor’ – as US Treasury yields increased after 2 April (Figure 5, blue dots). At the same time, the estimated co-movement of German Bunds with the ‘safe-haven factor’ remained stable. Looking at currencies, while the US dollar has typically appreciated following a deterioration in global risk sentiment, this co-movement switched signs in April 2025. By contrast, the co-movement of the euro exchange rate with the ‘safe-haven factor’, which has been historically close to zero, turned positive, closer to the usual behaviour of a safe-haven currency such as the Swiss franc.

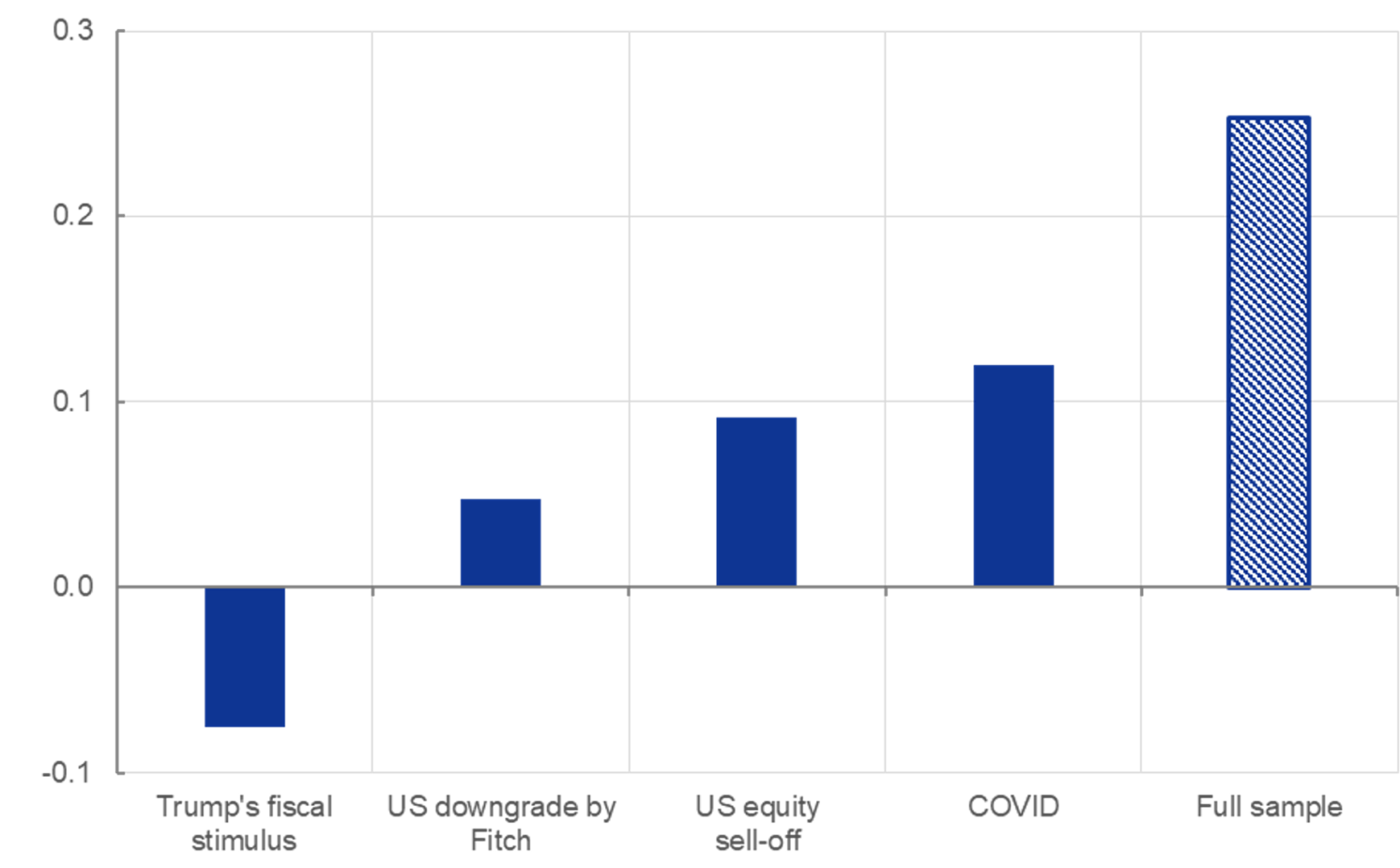

Instances of changing co-movement of the US dollar with the ‘safe-haven factor’ have at times been observed in the past. While the usual co-movement of the US dollar with the ‘safe-haven factor’ tends to remain broadly stable (as shown in Figure 5 with yellow ranges), the instances of changing patterns are not unprecedented. For example, Figure 6 illustrates that there have been several times in the past years when the co-movement of the US dollar with the ‘safe-haven factor’ declined or even turned negative. For example, a period of somewhat negative co-movement has been observed in the early months of 2017, after the introduction of the fiscal stimulus during the first presidency of Donald Trump. Further examples of a slightly lower co-movement of the US dollar with the ‘safe-haven factor’ include the months after the downgrade of US credit rating by Fitch from AAA to AA+ in August 2023, the period of US equity market sell-off in the fall of 2018, when the stock market priced in negative effects of the trade war with China, the slowdown in global economic growth and concerns about rising interest rates, as well as the Covid period in 2020, which was characterised by outflows from US Treasuries observed during the ‘dash-for-cash’ episode. Comparing these estimates with April 2025 (blue dot for USD in Figure 5), the most recent change in the co-movement of the US dollar with the ‘safe-haven factor’ has been substantial, which might suggest that the policy-related news and uncertainty were relatively pronounced, as compared to past episodes. In addition, strong currency market developments following the April event might have been reportedly linked to the rebalancing of hedging activity among international investors, covering currency risks related to previously unhedged exposures in US dollar-denominated assets. With respect to yield developments, US Treasury yield increases after the April 2025 episode were accompanied by the decline in measures of the convenience of US Treasuries. 2 Related academic research offers a broader perspective on the dynamics in longer-term US yields. Jiang et al. (2025b), as well as Jiang et al. (2025c) document a trend of declining US convenience yields in recent years linked to, among others, concerns about a deteriorating fiscal situation. Such concerns have also gained market attention in the recent months.

Figure 5 Co-movement of financial assets with a ‘safe-haven factor’

(index)

Sources: Haver Analytics and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Dots show the weights in the first principal component estimated from daily changes in the net effective exchange rate (NEER) of CHF, JPY, EUR, and USD (purged by monetary policy and macro shocks estimated using the model of Brandt et al. 2026); gold price returns (purged from the USD); the first difference of ten‑year government yields for the US, Japan, and the euro area; and the VIX. Red dots: sample from 1 January 2006 to 31 March 2025; blue dots: 1 April 2025 – 15 July 2025 (the sample covers several weeks to ensure a sufficient number of observations). Yellow area: +/- one standard deviation range of results using a three-year rolling window. The latest observation is for 28 July 2025.

Figure 6 Past events of temporary shifts in USD co-movement with the ‘safe haven factor’

(index)

Sources: Haver Analytics and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Bars show the weights of the USD net effective exchange rate (purged by monetary policy and macro shocks) in the ‘safe-haven factor’, as defined in Figure 3, estimated over the following selected periods of time: (1) ‘Trump’s fiscal stimulus’ 1 January 2017 to 1 June 2017, (2) ‘US downgrade by Fitch’ 1 August 2023 to 1 October 2023, (3) ‘US equity sell-off’ 1 October 2018 to 1 January 2019, (4) ‘COVID’ 1 March 2020 to 1 September 2020, and (5) ‘Full sample’ 1 January 2006 to 31 March 2025, as in Figure 5.

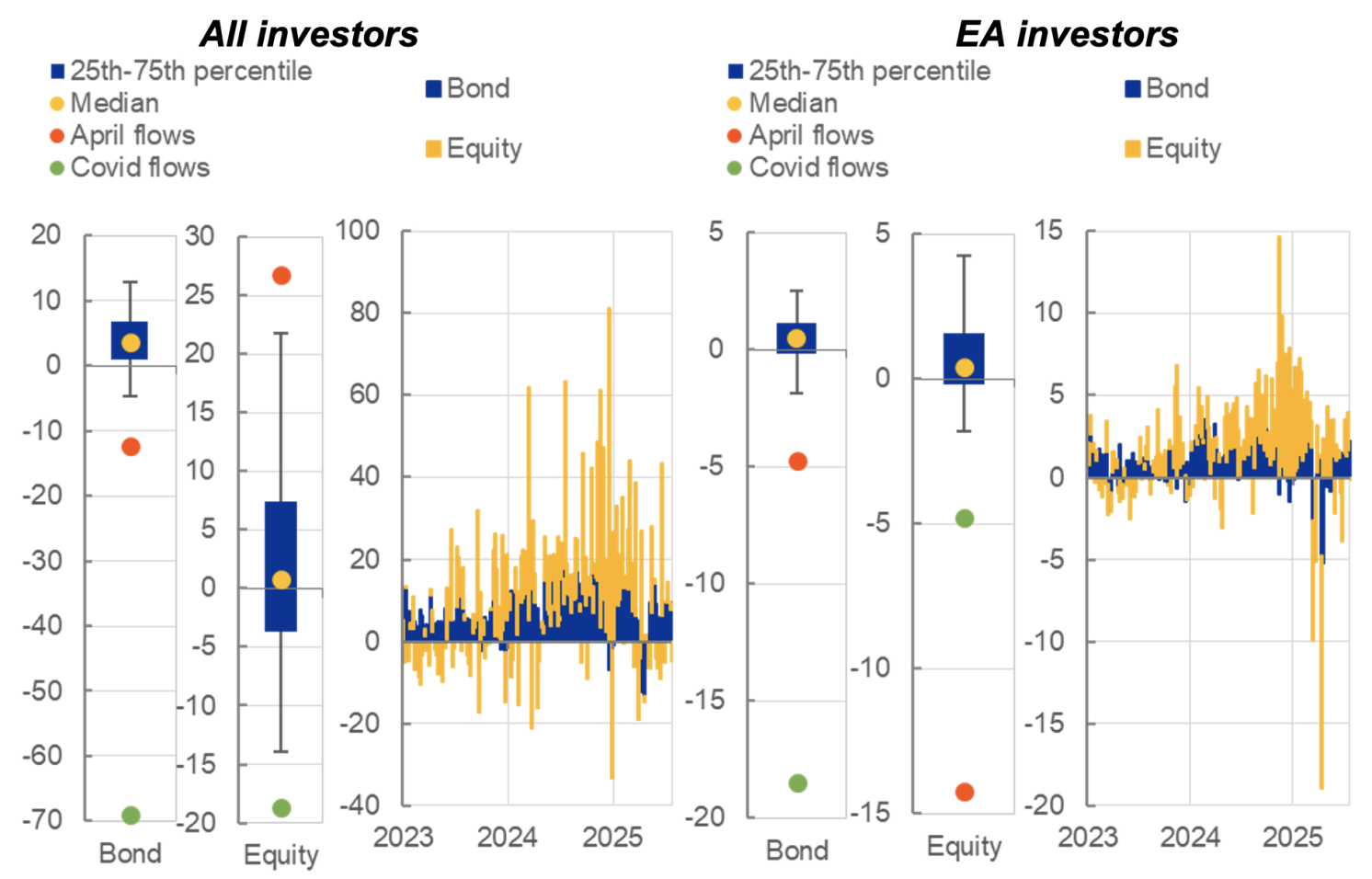

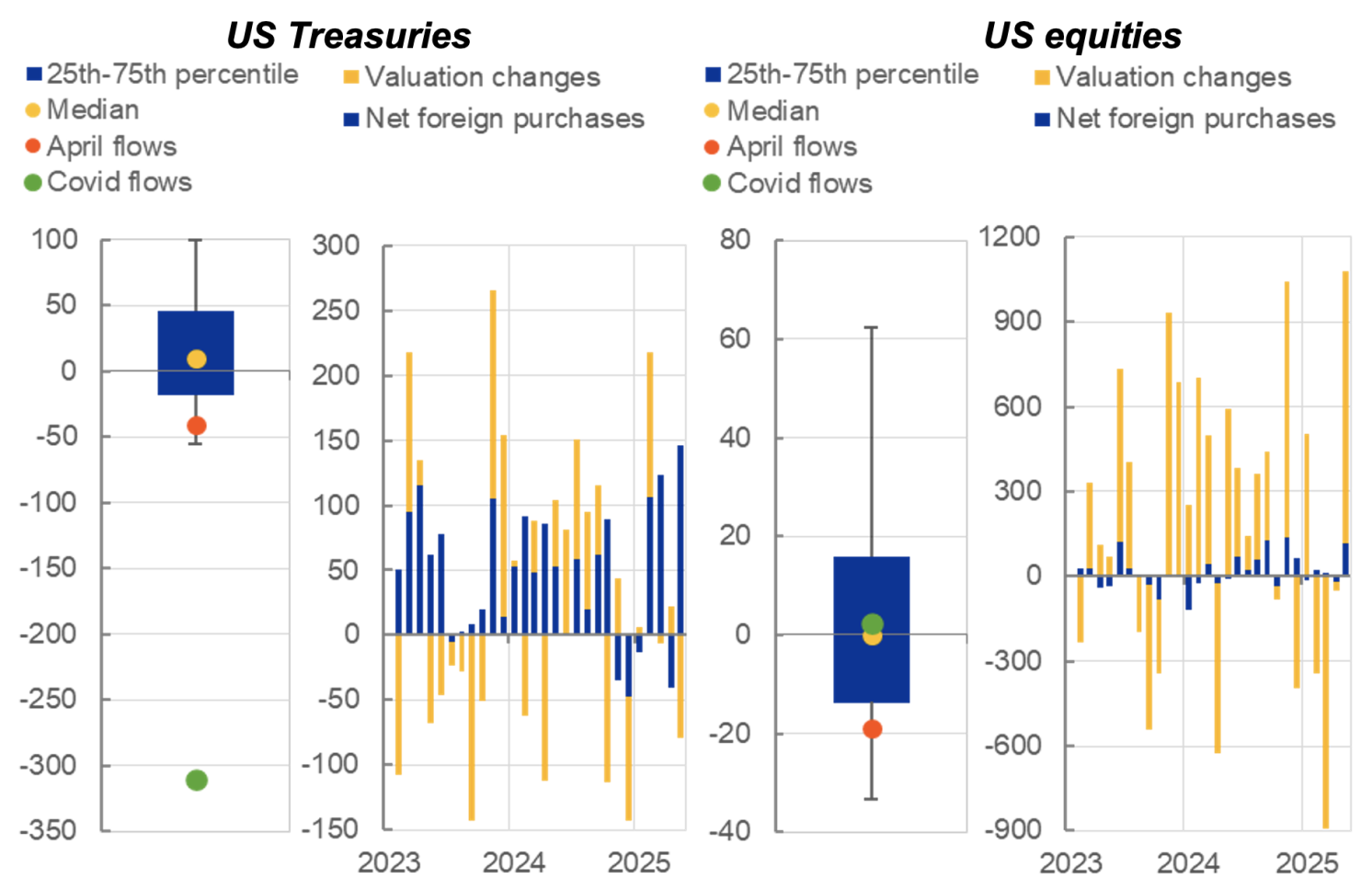

To give perspective on potential shifts in demand for US assets, US portfolio investment data for April show high outflows, but they were not unprecedented in scale and appear to have normalised since May. Apart from pricing indicators, currently available data on portfolio holdings do not show persistent outflows from the US (Figure 7). To obtain the most comprehensive picture, we review both EPFR and US Treasury data, which provide higher-frequency portfolio allocation estimates (EPFR data), and records of foreign portfolio holdings (Treasury data). Weekly data on flows into US portfolio investment funds showed substantial but temporary outflows in the first week or two immediately after the tariff announcements. Putting the net sales of US bonds in a historical perspective, they were lower than the 95th percentile of weekly outflows observed since 2012. However, foreign net purchases subsequently recovered, such that they remained broadly stable when taken for the months of April and May as a whole, for equities, bonds, and money markets, and added to the broad inflows observed since the elections (Figure 7, Panel A, left). 3Focusing on euro area investors, there is evidence of some outflows from US bond funds by these investors, albeit the pattern has been temporary so far (Figure 7, Panel A, right). 4 Data from the US Treasury International Capital System (TICs) indicate that foreign investors registered over $50 billion in net sales of total US long-term securities in April 2025, $40 billion of which were in US Treasuries (Figure 7, Panel B, left). The scale of net sales of US Treasuries by foreign investors in April is comparable to those observed in November and December 2024 and stands close to the 95th percentile of outflows since 2012, albeit nowhere near the rate of outflows from US Treasuries observed during the ‘dash-for-cash’ episode that followed the onset of Covid in March 2020 (Barone et al. 2022). Sales by foreign investors of US Treasuries were driven by net sales by private sector investors ($46 billion) rather than investors from the official sector (who purchased $6 billion). Looking across different economies, the largest sales of US Treasuries in April 2025 were recorded by Canada ($57 billion), the euro area ($21 billion), and China ($7 billion). 5 For US equities, US TICs data indicate net sales by foreign investors of around $19 billion in April (Figure 7, Panel B, right). However, the TICs data also suggest that foreign demand for US securities has rapidly recovered. Net foreign purchases of US Treasury securities rebounded to $146 billion bonds in May, while the equivalent figure for US equity securities was $114 billion. Overall, the currently available data point to some temporary rebalancing (for example related to adjustments of hedging), which so far appears to have stabilised. At the same time, policy uncertainty remains high, signalling possible further shocks, as concerns about policies seem to persist.

Figure 7 Investor flows to US assets

(USD billions)

Panel A: Net flows to funds investing in the US

Panel B: Net foreign purchases of US Treasuries and equities

Source: EPFR Global, Haver Analytics, US Treasury International Capital (TIC) System and ECB staff calculations.

Note: Panel A: ‘All investors’ refers to flows to US funds by all investors, ‘EA investors’ refers to flows from euro area-domiciled investors to US funds, based on EPFR Global data. ‘Bond’ and ‘Equity’ are based on EPFR definition of country flows. Distributions are calculated since 2012. ‘April flows’ refer to the weekly flows following Trump’s tariff announcement on 2 April, ‘Covid flows’ refers to the flows in the last week of March 2020 during the ‘Dash for Cash’ episode. The last observation is for 23 July 2025 (weekly data). Panel B: Net foreign purchases of US Treasury securities and equities, based on US Treasury International Capital (TIC) System data. Distributions are calculated since 2012. ‘April flows’ refer to the April monthly flows following Trump’s tariff announcement on 2 April, ‘Covid flows’ refers to the flows in March 2020 during the ‘Dash for Cash’ episode. The last observation is May 2025 (monthly data).

Authors’ note: Helpful discussions with and comments by M. Ferrari Minesso, A.-S. Manu, A. Mehl, F. Pires, T. Tomov, I. Van Robays and I. Vansteenkiste are gratefully acknowledged.

See original post for references